Reviews: Barbecue Apocalypse, The Sherlock Project, Life Is a Dream, and Madagascar

By Perry Tannenbaum

In a year that included Lucas Hnath’s The Christians, Robert Schenkkan’s The Great Society and Rebecca Gilman’s Luna Gale among the top contenders, I could only give Matt Lyle’s Barbecue Apocalypse a lukewarm endorsement for best new play of 2015, ranking it #13 among 27 eligibles that I read for that year’s Steinberg Awards. Nor did colleagues from the American Theatre Critics Association strongly disagree with my verdict, since Lyle’s dystopian comedy didn’t make the cut for the second ballot, when we considered our consensus top 10.

But before Charlotte’s Off-Broadway decided to stage this show at The Warehouse PAC up in Cornelius, they did some reading and balloting of their own. From January through March, the company offered monthly “Page to Stage” readings presenting two different plays on each occasion. Then they asked ticketholders to vote on which of the six plays they would like to see in a fully staged production. Less than two months after the votes were counted, Barbecue is back for my reconsideration as the audience favorite.

And on further consideration, I must credit director Anne Lambert and her professional cast for convincing me that Barbecue Apocalypse is even better than I thought it would be – far more to my liking than real barbecue.

Lyle would probably concur, since his patio hosts, Deb and Mike, are only grilling and basting because they want to avoid the embarrassment of having their friends – who are more trendy, stylish, and successful – see the interior of their home, decorated with lame movie posters. Deb succinctly describes her strategy as lowering expectations for the cuisine and the ambiance. Outdoors, she can point with pride to the fact that Mike has built the rear deck himself. Yet the barbecue event has obligated Mike to buy a propane grill off Craig’s List, and he’s afraid to light it.

He would also like Deb not to mention that he’s a professional writer, for his career earnings, after one published short story, now total 50 bucks.

All four of the guests feed the hosts’ sense of inadequacy. Deb is a decorator, foodie, and gourmet cook who makes sure to bring her own organic meat, and her husband Ash is a gadget freak, armed with the best new smartphone equipped with the most awesome apps. Win pretty much embodies his name, a former high school QB, now a successful businessman with Republican views. He lives to put Mike down and can seemingly get any woman he wants. Even his bimbo of choice, Glory with her Astrodome boobs, can claim formidable accomplishments, arriving late to the barbecue after nailing her Rockette audition.

What ultimately happens to this insulated suburban group reminds me of The Admirable Crichton, the excellent James M. Barrie tragicomedy I came across a couple of times during TV’s golden age, when colleges had core curriculums. A perfect butler to the Earl of Loam in Mayfair, London, Crichton and his betters were shipwrecked on a desert island in the Pacific, where his natural superiority emerged.

There are two basic differences between Barrie’s back-to-nature tale and Lyle’s. The shipwreck situation was reversible with rescue. Apocalypse isn’t. More to the point, Barrie was clearly targeting the blind rigidity of class distinctions. Here if we consider the implications of Barbecue Apocalypse, Lyle seems to have modernity in his crosshairs – how our world warps our aspirations and our self-worth, how it channels us into modes of living that are far from our authentic selves.

In the cramped storefront confines of the Warehouse, Lambert doesn’t attempt to design a deck that lives up to Mike’s pretensions, and Donavynn Sandusky’s costume designs are similarly déclassé, especially for the nerdy Ash. This robs Lyle’s concept of much of its slickness, which for me turned out to be a good thing. Aside from the Craig’s List mention, Lambert also dropped in a couple of local references that added to the overall homespun flavor.

Becca Worthington and Conrad Harvey were nearly ideal as our hosts, keenly aware of each other’s limitations and their own, yet visibly crazy for one another. Worthington with her status-conscious rigidity and stressing was clearly the closest actor onstage to Lyle’s vision, beautifully flipping her “We suck” persona after intermission and the apocalypse, when a full year of roughing it has elapsed. Harvey was more than sufficiently cuddly and self-deprecating – but credulity is stretched when a man of such size and stature is repeatedly dominated by his adversaries.

If you can accept that Greg Paroff was ever on a football field, let alone as a QB, you’ll be quite pleased with how he handles Win’s asshole antics. He is confident, he is arrogant, and if he’s possibly past 40, that only increases the disconnect between Win and his limber Rockette. Julia Benfield is absolutely adorable as Glory, and I absolutely adore how she’s still mincing around in high heels when she makes her disheveled entrance in Act 2. We totally believe that her familiarity with Tom Wopat doesn’t extend to The Dukes of Hazard in the ‘80s.

Probably not the best moment for Lambert when she cast Cole Pedigo and Jenn Grabenstetter as Ash and Lulu. They should remember the ‘80s, but I needed to stifle my doubts. Wardrobe and just the way he’s absorbed in his iPhone might help Pedigo out – and make him less wholesome, winsome, and juvenile before the apocalypse. Grabenstetter overcomes all objections when free-range Lulu gets snockered on generic canned beer, and both Pedigo and his scene partner truly click when adversity brings Ash and Lulu to a new lease on life in Act 2. I believe that’s an antler dance.

I won’t disclose what happens when Maxwell Greger walks on for his cameo deep in Act 2, but I do respect how Lyle makes him earn his paycheck with a sizable monologue. Greger does the denouement with a slight manic edge, and the technical aspects of his departure are impressively handled.

So it’s fair to say that apologies are in order for rating Barbecue Apocalypse in the middle of the pack when I first read it. Or excuses, since a rational man resided at the White House in 2015, and apocalypse seemed so fantastical.

But hold on. Charlotte’s Off-Broadway has already programmed two other plays from their “Page to Stage” readings for two fully-staged productions in the near future, Susan Lambert Hatem’s Confidence (and The Speech) for September and Lauren Gunderson’s Exit, Pursued by a Bear for next February. Maybe when these runner-ups get fleshed out, supporters of Lyle’s winning script might reconsider their votes!

A Catch-All Catch-Up

Our recent travels to Greece, Israel, and Jordan compelled us to miss a bunch of high-profile openings after we reviewed the reinvented Rite of Spring at Knight Theatre on April 6 and CP’s On Golden Pond the following evening. Even before we left, we had to pass on the Charlotte Dance Festival and CP’s Elixir of Love so we could adequately prepare for our trip. To see the birthplace of theatre, the Holy Land, and Petra, we had to miss out on the BOOM Festival, the reprise of Beautiful: The Carol King Musical, and the opportunity to host a pre-show preview of The Marriage of Figaro for Opera Carolina.

New openings when we returned were a must, so we hit the ground running with Charlotte Ballet’s Spring Works and Symphony’s Brahms-and-Bartok program. But our need to catch up with Carolina Shakespeare’s Life Is a Dream made us put off seeing PaperHouse Theatre’s Sherlock Project until it second week. It gets complicated. But I’ve tried to get up to speed while working on more reviews and features. File these under gone but not forgotten:

The Sherlock Project – So a dozen actors and writers collaborated on PaperHouse Theatre’s mash-up of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story gems, producing a script that follows three guiding principles: keep it funny, keep it moving, and don’t, don’t, don’t ever explain how the great Sherlock Holmes arrives at his incredible deductions. Going back to their roots at the Frock Shop on Central Avenue, PaperHouse and director Nicia Carla found a frilly complement to the Victorian chronicles of Dr. John Watson.

But the frame of the story was wholly new, telling us that the deadeye detective in the deerstalker cap is a woman. Watson protects the woman who should be credited with all the purported exploits of Scotland Yard’s Inspector Lestrade because he knows that Sherlock is right: The general public is even less prepared to believe a female is capable of such brilliancies than Watson is.

Besides all of the Sherlockian brilliance and nonchalant arrogance, Andrea King reveled in all of the detective’s eccentricities, whether it was shooting up a 7% solution of cocaine, tuning up a violin, or lighting up a calabash pipe. Opposite King’s insouciant self-confidence, Chaz Pofahl wrung maximum comedy from Watson’s wonder and timidity – a phenomenon compounded by the gender factor as Pofahl switched from paternal protectiveness to awe or terror while King wryly twinkled and smiled.

The two main supporting players slipped into multiple roles, Angie C as a cavalcade of damsels in distress and Berry Newkirk in the plumiest cameos, ranging from the dull-witted Lestrade to the razor-sharp Professor Moriarty, mythically uncatchable. Apart from directing behind the scenes, Carla conspired in the action as Mrs. Hudson, Holmes’s discreet housemaid. Carla not only ushered in Sherlock’s distraught clientele or evil adversaries, she also presided over scene changes, when audience members had to exit the Frock Shop’s parlor to a murder scene in the adjoining room or out on the porch when Sherlock was pursuing… something. Had to do with fire.

Or when it was intermission, time for little cucumber sandwiches.

The whole show was a wonderful diversion. PaperHouse had to add another performance to their run, which we caught last Wednesday, and the remaining nights were already sold out. Like the PaperHouse faithful, I couldn’t get enough of The Sherlock Project. I wanted lots more – beginning with how did Sherlock deduce that Watson had just come from Afghanistan when they first met?

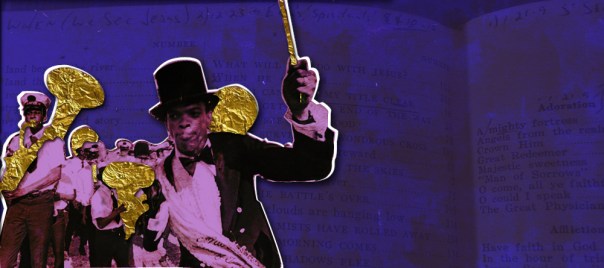

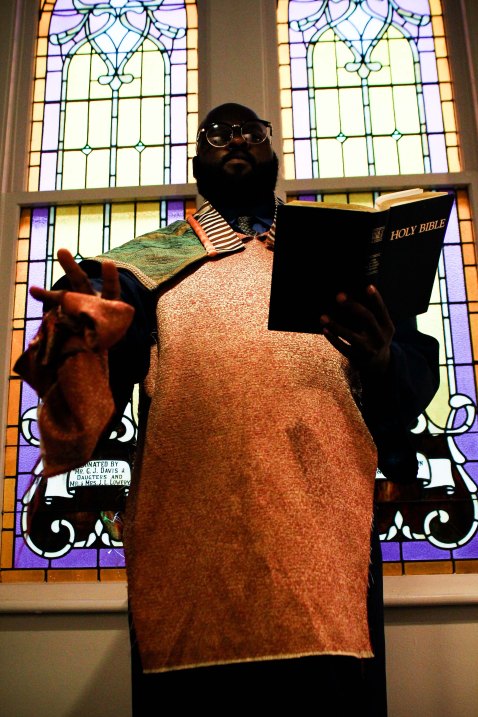

Life Is a Dream – Convinced it was a comedy rather than a political melodrama, Shakespeare Carolina and director S. Wilson Lee kidnapped Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s classic, written during Spain’s Golden Age, and transported it more than three centuries forward from a mythical Poland to a mythical Las Vegas. There in a seedy club on the strip, the two factions with their eyes on the throne were Frank Sinatra’s Rat Pack and Marlon Brando’s Wild Bunch.

Lee’s wild conceit didn’t do nearly as much harm as I thought it would, mainly because ShakesCar didn’t have the budget to carry it too far at Duke Energy Theatre, and the strong cast mostly played their roles as the text, sensibly adapted by Jo Clifford, said they should. So much depended on the broad shoulders of David Hayes as Segismundo. Heir to the throne of Poland, Segismundo has been locked away Prometheus-like in a mountain dungeon for his whole life by his father, King Basilio, who is foolishly trying to ward off the dire destiny predicted by an astrologer.

A boiling rage seethes inside of Segismundo, and a less mightily built actor than Hayes might need to strain himself to encompass it. Hayes projected the mighty rage rather naturally, which made it easier for him to flow convincingly into Segismundo’s softer emotions when – before he has even suspected his royal lineage – he is handed the Polish throne and the power to act on his newly awakened sexual urges as he sees fit.

Called upon to give a far more nuanced performance as Basilio, Russell Rowe delivered. Yes, he was cruel, but also conflicted, with a lifelong dread deftly mixed into his forcefulness. Though I feared the convoluted plot might be abridged or simplified, the intrigue, the complexity, and the epic monologues were almost entirely intact. As the vengeful Rosaura, Teresa Abernethy brought forth the masculine-feminine blend that the transgendered Clifford was aiming for in her translation, and James Cartee, an actor who often keeps nothing in reserve, showed unusual probity and maturity as Clotaldo, even as he tried to figure out his long-lost child’s gender.

Nobody was more suavely dressed by costume designer Mandy Kendall than James Lee Walker II as Astolfo, the successor that Basilio wanted if the true heir didn’t pass his test. But if anybody was victimized by Lee’s Rat Pack concept, it was Walker. I have no idea why he persisted in speaking so rapidly and unintelligibly, unlike any work I’d seen from him before. Was he attempting a Sammy Davis Jr. imitation? Couldn’t figure out what accounted for this curious outing.

Betrothed to this strange hipster, Maggie Monahan beautifully brought out the agonies of queen-to-be Estrella. Maybe the most Shakespearean role in this ShakesCar production was Ted Patterson as Clarin, who tags after the disguised Rosaura from the opening scene, as either her companion or servant – but definitely our clown.

On the strength of this effort, theatergoers can be excited about ShakesCar’s next invasion of Spirit Square, The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus at Duke Energy from June 28 to July 7.

Madagascar – Okay, so I’ll grant that the musical adaptation of the 2005 Dreamworks film didn’t have the gravitas of the greatest Children’s Theatre of Charlotte extravaganzas of the past like their Boundless Grace and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe – or the bite of Ramona Quimby and Tales of a Fourth-Grade Nothing. But this confection was nearly perfection. Under the direction of Michelle Long, Madagascar hit a family-friendly sweet spot, straddling the realms of cartoon silliness, cinematic adventure, and theatrical slapstick and dance. I just didn’t like the deejay, everybody-get-up-and-act-stupid thing.

Scenic design by Jeffrey D. Kmiec never lost its freshness thanks to a slick stage crew and the eye-popping lighting by Gordon W. Olson, while the animal costumes by Magda Guichard probably made the strongest case for live theatre against multiplex animation. Choreography by Tod A. Kubo chimed well with Long’s direction, which used areas of McColl Family Theatre that rarely come into play.

Centering around four animals that break out of Central Park Zoo, Madagascar introduced us to Marty the zebra and his wanderlust. We moved swiftly from there. Following the lead of four penguins bound for Antarctica, Marty escaped the zoo, seeking a weekend in Connecticut. Not only are police, animal control, and TV bulletins on his trail, so were his pals Gloria the hippo, Alex the lion, and Melman the giraffe. Embarking underground in the Manhattan subway, Marty hardly stretched credulity much further by winding up off Africa.

Deon Releford-Lee was a spectacular triple-threat as Marty, but what dazzled most was the multitude of gems in this supporting cast, beginning with an intimidating Alex from leonine Traven Harrington and – on stilts, of course – a timorous Melman from Caleb Sigmon. Dominique Atwater disappointed me as Gloria, but only because we didn’t get enough of our hippo after her first big splash. Olivia Edge, Allison Snow-Rhinehart, and Rahsheem Shabazz fared better, drawing multiple roles.

While the book by Kevin Del Aguila shone more brightly than the musical score by George Noriega and Joel Someillan, I was amazed that so much story and song could be squeezed into barely more than 60 minutes. Combined with last October’s Mary Poppins, the exploits of Madagascar prove that musical production is an enduring strength at Children’s Theatre. I can’t think of a season at ImaginOn that had sturdier bookends than these musicals that began and concluded 2017-18. The crowd that turned out for the final performance affirmed that the 7th Street fantasy palace has perfected the craft of producing family fare.

Not only that, it showed me that Charlotte families have spread the word.

At the other end of the Bach spectrum, the Leipzig cantor is the unchallenged master of solo works written for violin, cello, and organ. The Visiting Artist Recital Series at the Charlotte festival checks that Bach box as well. Highlighting the series, Bálint Karosi reigns at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church on Friday, June 16, when he will give the new Fisk organ a workout – with pieces inspired by Bach’s name, written by Schumann, Liszt, and others.

At the other end of the Bach spectrum, the Leipzig cantor is the unchallenged master of solo works written for violin, cello, and organ. The Visiting Artist Recital Series at the Charlotte festival checks that Bach box as well. Highlighting the series, Bálint Karosi reigns at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church on Friday, June 16, when he will give the new Fisk organ a workout – with pieces inspired by Bach’s name, written by Schumann, Liszt, and others.

Review: Charlotte Bach Festival~Opening Celebration

Review: Charlotte Bach Festival~Opening Celebration

For the second season in a row, I needed my wife Sue’s assistance in deciphering what Avital Lvova was saying onstage at Woolfe Street in a Henry Naylor drama. Last year, it was Angel, the story of the life and death of a Kurdish sharpshooter, where I was able to move closer to an empty seat near the stage and salvage some of Lvova’s performance. Lvova was back this year in Borders as another action hero, Nameless, a Syrian graffiti guerilla. No closer seats were available this time, so I struggled to comprehend even the basics of Nameless’s narrative as she lurked in a hoodie and thrashed on the floor in evasive actions.

For the second season in a row, I needed my wife Sue’s assistance in deciphering what Avital Lvova was saying onstage at Woolfe Street in a Henry Naylor drama. Last year, it was Angel, the story of the life and death of a Kurdish sharpshooter, where I was able to move closer to an empty seat near the stage and salvage some of Lvova’s performance. Lvova was back this year in Borders as another action hero, Nameless, a Syrian graffiti guerilla. No closer seats were available this time, so I struggled to comprehend even the basics of Nameless’s narrative as she lurked in a hoodie and thrashed on the floor in evasive actions. All that separates The Flying Lovers from ascending to the pinnacle of towering drama are length, conflict, complications, and plot. Instead, the blissful couple navigates upheavals that decimate their obscure hometown (ironically best known today as Chagall’s birthplace) and threaten to incinerate the Jewish people. Pogroms, the Russian Revolution, and the Holocaust toss the couple back and forth across Europe until they reach the safety of the US. More vividly than these obstacles, we remember the purity of the love that binds Marc and Bella together. This love helps them to soar above the troubles of our world – higher, they seem to levitate, because there are no plots or complications pulling them down.

All that separates The Flying Lovers from ascending to the pinnacle of towering drama are length, conflict, complications, and plot. Instead, the blissful couple navigates upheavals that decimate their obscure hometown (ironically best known today as Chagall’s birthplace) and threaten to incinerate the Jewish people. Pogroms, the Russian Revolution, and the Holocaust toss the couple back and forth across Europe until they reach the safety of the US. More vividly than these obstacles, we remember the purity of the love that binds Marc and Bella together. This love helps them to soar above the troubles of our world – higher, they seem to levitate, because there are no plots or complications pulling them down. By Perry Tannenbaum

By Perry Tannenbaum

Rapp first landed a role at Theatre Charlotte when she was 10 and transferred to Northwest in her junior year. “They are both truly such talented and good-hearted human beings,” she says of Pearce and Sistruck. “Working amongst them all these years has helped me grow as a performer watching the dedication they put into what they do. We have so much love amongst the three of us that even in this especially stressful time with the Blumeys, Spring Awakening and graduation, they make every day and every rehearsal feel like a celebration for me.”

Rapp first landed a role at Theatre Charlotte when she was 10 and transferred to Northwest in her junior year. “They are both truly such talented and good-hearted human beings,” she says of Pearce and Sistruck. “Working amongst them all these years has helped me grow as a performer watching the dedication they put into what they do. We have so much love amongst the three of us that even in this especially stressful time with the Blumeys, Spring Awakening and graduation, they make every day and every rehearsal feel like a celebration for me.”