“Eureka” and “Vanya” Agreeably Disagree

Heaven, Elysium, Utopia, Paradise, and Arcadia are all perfect places in our minds, too placid and static to be considered as settings for comedy, thrilling action, or drama. If you were in search of a perfect backdrop for the music of The Go-Go’s, you would more likely pick a city on the California coast, Las Vegas, or even Indianapolis than opting for heaven or the Elysian Fields.

That’s not how Jeff Whitty saw it when he conceived Head Over Heels. You get the idea that, after birthing Avenue Q, Whitty almost had free rein from the Oregon Shakespeare Festival to do anything he pleased. Whether he was inspired by the Elizabethan aura of OSF’s outdoor and indoor stages in greeny Ashland, Oregon – or bound to play up to them – Whitty reached back to The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia by Sir Philip Sidney, first published by the Countess in 1593.

Whitty had absolutely no intention of bridging the two eras – or smoothing the discordance between Elizabethan and Go-Go’s English. Whitty does tone it down a bit when Philoclea, the younger daughter of Arcadia’s King Basilius, tells her ardent admirer Musidorus to “Speak English, not Eclogue” when the shepherd boy begins his wooings.

At about the time that Head Over Heels premiered at OSF in 2015, Something Rotten!, with Will Shakespeare as its rockstar, was premiering on Broadway. That might explain the lukewarm reception that greeted Whitty’s show when it had its NYC premiere in 2018, for its Broadway run fizzled out in less than six months.

You can judge for yourself at spacious Duke Family Performance Hall as Davidson Community Playhouse rather splendidly presents its summer musical in nearly all of its gender bending glory. For this Metrolina premiere, projection designer Caleb Sigmon, scenic designer Ryan Maloney, and costume designer Yvette Moten fill the Broadway-sized stage on the Davidson College campus with eye-popping color and Hellenic style.

With the disclaimer that I’d never heard a single bar of Go-Go’s music before Head Over Heels came to our region, I can say that I delved into The Go-Go’s greatest hits afterwards on Spotify and listened to the original Broadway cast album. From the opening “We Got the Beat” onwards, the two generations of singers up at Exit 30 on I-77 beat them both.

Word of DCP’s excellence has extended its reach, and director Chris Patton and music director Matthew Primm have reaped the benefits. Belting the Go-Go’s “Beautiful” to her own mirror, Jassi Bynum is the vain elder sister, Pamela (a name apparently invented by Sir Philip). No less capable of letting loose, Kiearra Gary is the obedient “Good Girl” sister, Philoclea. And the well-established powerhouse, Nonye Obichere, is Mopsa, who seems for awhile to be a third sister until we learn that she is actually the daughter of the King’s steward, Dametas.

When Mopsa’s heart is broken, she will flee to Lesbos (wink, wink) and sing “Vacation.” Obichere slays at least as convincingly as the sisters.

It’s easy enough to get confused by the parents because they’re all white folk who fit nicely into Sidney’s Grecian mold but look nothing like their offspring. Yet Lisa Schacher, not seen hereabouts in a truly breakout musical role since the early days of QC Concerts, keeps her where-have-you-been-all-my-life belting capabilities under wraps until after intermission as Gynecia, the Arcadian queen. We’re not just talking Judy Garland belting, for Schacher crosses over the borderline to Whitney Houston territory along with Bynum, Gary, and Obichere.

Once whatever was clogging Tommy Foster’s larynx in the first moments of Saturday night’s performance as Dametas was expelled, the longtime veteran reminded us that he could also wail. Saddled with a more earthbound voice, Rob Addison brings a nicely grizzled dignity to King Basilius that is forceful enough for the lead vocal of “Get Up and Go” and his climactic king-and-queen duet with Schacher, “This Old Feeling.”

Kel Wright, whose pronouns are Kel and I in her coy bio, is the gender-fluid complication roiling the eternal placidity of Arcadia. She is the ardent shepherd boy Musidorus, Philoclea’s bestie since her tomboy days, who must disguise himself as an Amazon warrior, Cleophila, after he’s banished from Arcadia in order to regain access to his lady love.

Everybody seems to be attracted to Cleophila, though they come to all the possible conclusions about the Amazon’s true gender. It’s a mess – a hormonal thundershower that afflicts the King, the Queen, and their daughters. All of them scurry about in a mad passion that comes off with all the innocent merriment of a musical comedy. Adding to all of this hilarity is the disconnect between Wright’s tinniness and the Amazon’s virility, so feverishly irresistible to Pamela and her mom.

All of this mad pursuit, however, happens under the cloud of a prophesy that threatens Arcadia’s doom. A snake sent by Pythio, the Delphic Oracle, lets loose of a letter summoning King Basilius to the temple to hear the Oracle’s oracle. In Sidney’s original manuscript, not recovered until 1908, the prophecy is given concisely in verse at the end of the novel’s opening paragraph.

Thy elder care shall from thy careful face

By princely mean be stolen and yet not lost;

Thy younger shall with nature’s bliss embrace

An uncouth love, which nature hateth most.

Thou with thy wife adult’ry shalt commit,

And in thy throne a foreign state shall sit.

All this on thee this fatal year shall hit.

Whitty actually retains the adultery line – with its apostrophe! – but flips the plotlines of the elder and younger daughters. In Arcadia, Basilius is seeking to preserve his family and kingdom, but in Head Over Heels, he’s also battling to ward off the mass extinction of Arcadians. Forget about the “fatal year”: Each time one of the four prophecies is fulfilled, a flag will fall. If Basilius fails to confound the Delphic Oracle’s prophecy and the fourth flag falls… game over. If he succeeds in thwarting the prophecy even once, Arcadia is saved.

The roadblock to all this heroic questing and defying taking hold at Duke Family is the sensational Treyveon Purvis as the glittery Pythio, who describes themselves as a “non-binary plural.” No, that isn’t verbatim from Arcadia. We don’t need to understand every word of “Vision of Nowness” instantly as Pythio bodaciously belts it. If you don’t catch a phrase the first time or Purvis slurs it, you’ll get a second chance. Besides, the Go-Go’s lyrics are of little consequence once the song is done.

But the four prophecies and the fluttery flag drops are the whole damn evening, so when Purvis garbled every one of Pythio’s pronouncements – and the flag bit as well – much of what followed became equally incomprehensible. Why were those flags falling again? Was Foster wildly excited when he caught those falling flags, or was his Dametas frantically panicked?

Never could get a read on all these things until I sorted them out later at home. A few other gems had eluded me when I perused the script. For example, when Wright is lavishing her outsized voice on Musidorus’s “Mad About You,” the shepherd’s backup group are his sheep, altering the Go-Go’s deathless lyric to “Ma-ad about ewe.” Bleating as they sang? I don’t remember.

Nor did it quite register that Pythio’s backup were all snakes. So there was little chance for me to savor Purvis’s best line of the night: “Snakelettes, slither hither!” They are only named that one time, so catch it if you can.

Arguably, the main historic aspect of Head Over Heels was that it offered Peppermint, as Pythio, the opportunity to be the first openly trans actor taking on a major role on Broadway. There’s summery breeziness to this show and a cozy ending, not nearly as biting as Avenue Q. Maybe if the Broadway production had had the chance to run for a full summer, it might have found its legs instead of perishing in the dead of winter.

It’s the Go-Go’s, after all. Just don’t go in expecting the usual Jack-shall-have-Jill windup. Whitty remains a bit queer.

By Perry Tannenbaum

Beyond the first two capital letters ever used by playwright christopher oscar peña in any of his titles, peña injects a joke or two into his newest, how to make an American Son. Within a few minutes, we learn that Mando, the father of the title character, Orlando, doesn’t have the slightest interest in parenting. Mentoring or shaping Orlando as he journeys from childhood to adulthood seem to have been forgotten, replaced by a compulsion to provide him with the best that money can buy.

And then by setting limits on what the kid buys on Dad’s credit. Not so easy when you haven’t been concerned with parenting or tough love for the past 16 years.

We also learn that Mando, the founder/CEO of a successful janitorial firm, is a Honduran immigrant and his son was born in the US. So Orlando is an American! In the crudest sense, the fabrication of our young antihero was successfully consummated in dimly-lit intimacy.

Clearly, peña is working with a more nuanced definition of what an American truly is, pursuing a more nuanced answer on how one is made. Orlando is gay, piling fresh levels of challenge and difficulty on his quest to reach a feeling of belonging while making that quest more widely relatable to any member of a family with someone who has come out. Mom and Dad, to their credit, have accepted their son’s sexuality, though Mom (never seen) prefers that Orlando date Latinos.

Whether or not he has been bolstered by his parents’ liberal leanings, Orlando is fairly strong-willed. Yet he also has that second-generation softness of suburban children who take their money and privilege for granted, never needing to stoop or get down on his knees to clean a toilet at home or at work. We get different perspectives as new characters take us from Mando’s office to Orlando’s elite school, the interior of a schoolmate’s car, and the lobby of Mando’s most valuable client.

Toss in a careful, diligently hard-working immigrant, who reflects Mando’s work ethic more faithfully than his son, and you can see why peña’s piece appeals so strongly to Common Thread Theatre Collective. Formed last summer by theatre faculty at Davidson College and North Carolina A&T University, the nation’s largest HBCU, Common Thread pushes back against the top-down power dynamic of most professional companies. The Collective seeks to include rather than exclude perspectives of women, LGBTQ+ artists, and artists of color while highlighting today’s most critical issues.

At Barber Theatre, on Davidson’s liberal arts college campus, it’s safe to say that immigration, class divisions, and homophobia fit the bill. White folks aren’t banned from this conversation, but they comprise only one-third of peña’s cast and get an even smaller cut of the stage time. There’s a breezy lightheartedness at the core of Mando’s attempts to check Orlando’s extravagances – a new leather bag for school, tickets to a Madonna concert, and an impulse purchase of Rage Against the Machine tickets to impress the white schoolmate he’s hoping to date.

Comedy lurks in the details because Orlando can run circles around his dad with his tech savvy while he remains so self-centered and immature. A native Honduran who has assimilated more thoroughly than Mando, Rigo Nova brings a streetwise authenticity to this gruff businessman even though has chosen a more urbane path for himself. He makes Mando a juicy target for his son’s slights and barbs, only adding more to the impact of his own thrusts with his scarcely filtered vulgarity.

Directing this play in her Metrolina debut, Holly Nañes calls for a nicely calibrated mix of shock, resentment, curiosity, and cool from Nicolas Zuluaga as Orlando when his dad finally sheds his customary benevolence and test-drives the idea of punishment. There are no onsets of diligence, penitence, or heightened seriousness in Zuluaga’s demeanor as he dons a janitorial uniform for the first time in his life. Nor is there any childish pouting or seething resentment as he’s paired up with Rafael, the lowly immigrant.

That breeziness while playing with fire sometimes reminded me of Athol Fugard’s Master Harold in his insouciant superiority; at other times, when seducing Rafael, Curley’s wife from John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men came to mind – an undertow of foreboding as Orlando’s differences with Rafael mirror those he has with his dad. Zuluaga’s almost slothful dominance is nicely complemented by Richard Calderon’s wary and subdued debut as Rafael. He isn’t busting his butt either as he engages Orlando, but he’s working rather than slacking. We can see what Rafael has been through and that he knows the drill.

Striving to get over on Sean, the school jock and Rage Against fanatic, Orlando instinctively drops his cool superiority. We surely see that Logan Pavia as Sean is playing him, ruthlessly confident that he can get what he wants. Maybe Pavia’s audacity shocks you anyhow. The same sort of flipflop happens when Mando shows up Dick’s office, hoping his most-valued client will renew his contract.

We don’t see Rob Addison as Dick until late in the action, and it might have helped a little if we’d gotten to know the white plutocrat better. For this is Addison’s only scene, arguably the most explosive scene of the night as two generations of whites and Hispanics square off. A second blowup afterwards, registering somewhat less on the Richter scale, happens when Mando peeps in on his son and Rafael at precisely the wrong moment.

Stacy Fernandez as Mercedes, newly promoted to become Mando’s general manager, doesn’t witness either of these blowups – or Orlando’s humiliation in Sean’s car. That’s a double humiliation for Orlando because his dad has paused his promise to buy him a car. Without these contexts, Mercedes has a radically different perspective on how to make an American son than the one taking shape for Orlando and his dad. Fernandez gets the opportunity to express this bitter viewpoint in a blowup of her own, and she does not misfire – what she sees, we must acknowledge, is no less valid than what the men see.

Slick and antiseptic, Harlan D. Penn’s glassy set design thoroughly purges Mando’s office of any color, artifact, or furniture that might be regarded as ethnic. Even the bookcases are vacuously neutral, populated with trophies, plaques, correspondence, business records, and binders. As the script swiftly underscores, no books. One shelf is entirely devoted to cleaning liquids, always at the ready in case a fingerprint sprouts up on a glass window or a door.

We may yearn occasionally for less polished flooring to separate us from Mando’s desk and the full-size Honduran flag that hangs vertically behind him. The frequently mopped surfaces evoke a sterile lab or an ER lobby where dirt comes to die. Or with that flag perennially in the distance, we might view that empty space as the desert that Latinx immigrants have crossed to get here. Or the spanking clean desert they found when they arrived.

Peppered with a contemptuous sneer, what Mercedes would tell you in answer to peña’s prompt is that both father and son have effortlessly become Americans without even trying. The answer Mando and Orlando would give you is grimmer than that.

By the end of the evening, thanks to peña’s deft plotting, there are battle scars supporting both points of view. The Donald’s wall across our southern border is the worst by far, but peña methodically shows us that it isn’t the only one.

From God of Carnage to Hand to God to The Toxic Avenger and beyond, I’ve seen many of the original Broadway and Off-Broadway shows that Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte has gone on to present in their Queen City premieres. What is singular about Silence! The Musical, perhaps unprecedented, is the fact that the original New York production at PS122 was unquestionably smaller, shabbier and more low-budget than the one currently playing at Hadley Theater on the Queens University campus.

This Charlotte debut is seven years more distant from Silence of the Lambs, the Academy Award winning thriller that Hunter Bell and his musical cronies, Jon and Al Kaplan, targeted with their satiric mischief and malice. Back in 2012, I was already bemoaning my failure to refresh my memories of the 1991 film with a full viewing before I went to see this nasty sendup.

Oops! I neglected my own warning last week, allowing my aging VHS tape to gather seven more years of dust before heading out to see what director Chip Decker and his cast would do in their assaults on Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins. I must confess that my perspective was more than a little skewed, for by August 2019, I found myself remembering the Bell/Kaplans musical at least as well as the Jonathan Demme film.

What I remember most about the PS122 show, besides its fundamental crassness and cheapness, was its dimly-lit, wicked cult ritual ambiance. Reasonably enough, Decker and his design team are going for something different: a musical! Evan Kinsley’s set design spans the Hadley stage and so does Emily Hunter’s choreography, with a gamboling chorus of Lambs in a matched set of wooly white ears by Carrie Cranford.

Where Actor’s Theatre, Off-Broadway, and Demme intersect best are in the takeoffs on Foster and Hopkins. Leslie Giles has a veritable feasht exaggerating FBI trainee Clarice Starling’s lateral lishp, surely enough to convulse audiences seeing this Foster takedown for the first time, but not as mean and relentless as the mockery Jenn Harris dished out in New York. What will further delight Charlotte audiences, however, is the sweet bless-her-heart drawl that Giles lavishes on Clarice’s entreaties and interrogations – and her expletive explosion when her sexist boss slights her is a comedy shocker.

There was plenty of seediness in the original Lambs for the Kaplans and Bell to build on. Clarice’s confrontation with Hannibal the Cannibal results from her boss’s unsavory idea of sending Starling down into the bowels of a criminal madhouse to pick Lecter’s brain – hoping that the psychiatric insights of one serial killer can help the FBI catch another. Maybe some kind of natural attraction will coax Dr. Lecter into opening up. Clarice’s descent into the Baltimore loony bin confirms that a rare visit from a woman will indeed rouse the snakes in the pit as the trainee walks the gauntlet of cells leading to Lecter.

A couple of the arousals fuel the most memorable moments of ejaculation and rapture. After the best spurt of physical comedy, we reach the innermost sanctum where the Cannibal is caged, and the shoddy cheapness of his protective enclosure becomes one of the show’s numerous running gags. At the climax of the first Lecter-Starling tête-a-tête, Rob Addison gets to deliver Hannibal’s deathless love ballad, “If I Could Smell Her Cunt.”

Addison’s rhapsody mushrooms into a ballet fantasia centering around Ashton Guthrie and Lizzie Medlin’s pas-de-deux as Dream Lecter and Dream Clarice. While Hunter’s choreography is more than sufficiently purple and passionate, we fall short on crotch crudity from Giles, and Cranford’s costuming muffs the opportunity for the Lambs to deliver a labial flowering. Yet it’s here that Addison is surpassingly effective, for his creepy drone as Lecter not only replicates the familiar Hopkins bouquet, but his singing voice is robust and raspy. We stay firmly in an Off-Broadway joint during Addison’s rhapsodizing instead of detouring, as PS122 did, into Broadway spectacular.

Other than the equine Mr. Ed, I couldn’t fathom what Jeremy DeCarlos was going for in his portrayal of the at-large crossdressing serial killer Jame Gumb, alias Buffalo Bill. To make things worse, production values reach their zenith when DeCarlos sings his showstopper, “Put the Fucking Lotion in the Basket,” to his latest captive, Senator Martin’s suitably plump (“Are You About a Size 14”) daughter Catherine. If Kinsley hadn’t troubled to elevate his sadistic serial killer to such a commanding height on his impressive set, flimsier security arrangements similar to the Cannibal’s would have played funnier.

Rest assured that verisimilitude isn’t a top priority elsewhere in Decker’s scheme. Kacy Connon excels as both Senator Martin and her daughter Catherine while Ryan Dunn shapeshifts from Clarice’s dad to agent-in-charge Jack Crawford, all without discarding their Lambketeer ears. Dunn’s eyeglasses shtick worked every time with the opening night crowd, and in welcoming Clarice to the institutional home of Hannibal, Nick Culp sleazily Clarice set the tone for the unfettered lechery to come.

Clarice lucks out when Crawford cruelly reassigns her, but she shows up unawares and unprepared at Buffalo Bill’s lair. That disadvantage results in the last of the three scenes we remember best from the screen thriller, the duel to the death on Bill’s home turf in pitch darkness, Clarice armed with her automatic pistol and the psychopath wearing night vision glasses. Peppered with song (“In the Dark With a Maniac”), this parody comes off as winningly as the great prison sequence where we first encountered Lecter – and better than the previous climax when the Cannibal escapes.

Hallie Gray’s lighting design is a valuable asset when tensions intensify, and Kinsley’s tall scenery isn’t a total waste. At times, it adds to the absurdity of the Lamb chorus, but it pays off most handsomely at the end in Hannibal’s demonic farewell, adding a dimension that even Hollywood couldn’t boast.

Graphic novelist Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home grabs – and sustains – our attention in large measure because the title is a misnomer, the nickname given by Alison and her siblings to the family business, the Bechdel Funeral Home. Yet as the story unfolds, with its cargo of closeted homosexuality, sexual molestation, and suicide, we realize that Alison is stressing – and cherishing – the fun times she had with her siblings and her troubled dad. Sweetened by Lisa Kron’s stage adaptation and juiced by Jeanine Tesori’s music, the fun in Fun Home gains further momentum.

It keeps rolling in the Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte production at Queens University with lively stage directing, choreography, and preteen actors playing the young Bechdel pranksters. Aiming in that enlightened direction, set designer Dee Blackburn starts with the thrust stage configuration I saw at Circle in the Square for the Broadway, but she departs from the funereal darkness that characterized the New York run and the national tour. Abetted by Hallie Gray’s lighting design, Blackburn gives us the kind of bright home that Alison’s neat freak dad might fuss over.

Or not. We also get darkness when Bruce, Alison’s dad, summons her to assist him in prepping a cadaver – and on numerous occasions when we leave the Bechdel house. Bruce’s nocturnal rambles, creepy and predatory, might occur far away on a family trip or in his car cruising the neighborhood for prey. If you’ve seen Fun Home before, you might find Bruce’s rambles more chilling, since his household isn’t an Addams Family lookalike. Bechdel’s original subtitle, “a family tragicomic,” wickedly sets the tone.

The most fun is when the three Bechdel kids do the big “Come to the Fun Home” song, pretending to cut a TV commercial for the funeral parlor, with choreography by Tod Kubo that captures all the goofy giddiness of the previous productions I’ve seen. Both Allie Joseph and Ryan Campos distinguished themselves at the start of this season in Children’s Theatre of Charlotte’s admirable Matilda, while Donavan Abeshaus has flown a little more under the radar, appearing as the young anti-hero in Bonnie and Clyde at Matthews Playhouse in February 2018. They make a fine set of Bechdel sibs now, though Joseph once again draws the plumiest role.

Joseph is so brash and brilliant as Small Alison that she steals a little of the thunder from Amanda Ortega’s somewhat understated Medium Alison, the collegian who discovers her true sexuality at Oberlin and comes out as a lesbian. Ortega’s “Changing My Major” (to Joan, her first lover) was still an uproarious showstopper for those at opening night encountering it for the first time, though it brought nothing fresh that I hadn’t seen, but Lisa Hatt as our narrating Alison did offer something new, besting even the Tony-nominated Beth Malone as our storyteller.

Maybe director Chip Decker believed she could be more than what she was on Broadway and on tour, for liberating Hatt – just by freeing her from the nerdy sketchpad she perpetually carried – is likely the foundation for all the Hatt achieves. Even when focus is elsewhere, on Bruce or one of the other Alisons, Hatt’s reactions matter, and her delivery of the climactic “Telephone Lines” is star quality. Yet there’s less of a feeling that this Alison has it all worked out after coming to terms with her sexuality and the fact that, as a graphic novelist, she isn’t going to join Faulkner and Hemingway in her English teacher dad’s pantheon. Hatt strikes me as a less confident Alison, still searching.

Hatt’s take on Alison allows Rob Addison as Bruce to be a little less formidable – more lifesize – than Michael Cerveris was on Broadway. A little more nuance helps because the ground has shifted somewhat since 2015, when Fun Home premiered, under the issues that Alison’s dad straddles. Though nothing excuses Bruce’s sexual predatoriness, fears of exposure and disgrace as a homosexual may be prime reasons why Dad is so rigid, regardful of others’ impressions, and so virulently bossy. You can believe it when Addison lets down his guard and plays with Young Alison at the start of Fun Home, and you can eventually see why this might be so atypical of Dad that our narrator would cherish the memory.

Of course, the tortured and torturing Bruce can have more empathy with Alison – and be more grimly protective of her – than Helen Bechdel, her mom, and Lisa Schacher delivers a nicely nuanced portrait. Submissive, disapproving, and beneath it all, the caretaker, with a self-loathing to match her husband’s. Maybe a little more nuance from Sebastian Sowell as Joan to go along with her invincible cool would help me see why everyone, especially Medium, is so impressed with her. You can see, however, that a medium-energy Medium Alison is attractive to her.

Rounding out the cast as a couple of Bruce’s trespasses, Patrick Stepp shows enough self-awareness as Roy, the yard boy that Bruce plies with drinks – while Mom is elsewhere in the house! – to let us suppose that all this isn’t as surprising to Roy as it might be to us. Or unprecedented. In a scene that Alison isn’t narrating from her own experience, giving Dad a small benefit of the doubt is probably the perfect path to take. A little more sugar – and a soaring flight of fancy – will help Alison bring an uneasy but upbeat closure to her engaging memoir

For all of its bells and whistles, Simon Stephens’ The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time evolves into something quite simple – a mother, a father, and their autistic son who are all trying to be better. I’ve seen the show three times in less than three years, first on Broadway, then on in its national tour, and now in its current incarnation at Hadley Theater on the Queens University campus. Each time, I’ve found new details to unpack, new facets of character to consider. Of course, the Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte version breaks the mold set by Marianne Elliott, who directed this adaptation of Mark Hadden’s novel on Broadway and on tour. In his stage direction and scenic design, Chip Decker takes his cues from Elliott and her scenic designer, Bunny Christie, but it’s obvious the Decker and the three actors he has cast as the Boone family have their own ideas.

Christopher Boone is the inward 15-year-old with autism who savors his solitude and freaks if anyone touches him, including Mum and Dad. He’s fairly oblivious, inexperienced, and clueless about human relationships, so the marital dynamics between his parents are totally unexplored territory. Yet Christopher functions on such a high mental level, an Asperger savant syndrome level, that he regards his special ed classmates as stupid and is highly confident that he can pass his A-level math tests years before “normal” schoolkids are allowed to take them. With Chester Shepherd taking on this role in his own clenched, volatile and vulnerable way, I saw more clearly why the prospect of postponing these tests was such an unthinkable catastrophe for him. Not only does Christopher notice everything that well-adjusted people allow to slip past them, he can also recall details with the same precision, like every item he extracted from his pockets on the night he was arrested and questioned at the Swindon police station. So it figures that Christopher would plan his future with the same persnicketiness, and that a single displaced detail – like postponing the date when he would pass his maths – would throw him into a spasmodic fit of panic.

Or so it seems with Shepherd emphasizing Christopher’s hair-trigger sensitivities. We see him at the beginning of his epic journey, huddled over his neighbor Mrs. Shears’ dog, Wellington, who lies there lifeless, skewered by a pitchfork. Christopher is obviously a prime suspect for Mrs. Shears, so she calls the police. Uncomfortable around other humans, Christopher doesn’t react well when a policeman arrives to interrogate him. Dad must come down to the station, after Christopher is arrested for assaulting the cop, to explain his son’s condition – a not-so-subtle indictment of police enlightenment. Twice shaken by the evening’s experiences, Christopher resolves to solve the mystery of who killed Wellington. That beastly affair doesn’t seem to concern the police, perhaps the second count in Hadden’s indictment.

As Christopher well understands, solving the Wellington mystery will force him to engage with other people, especially neighbors whom he has previously shunned. This aversion isn’t readily quashed, cramping the investigation when Christopher decides to question the warm and eccentric Mrs. Alexander. When the hospitable lady invites him into her apartment, Christopher refuses, and when Mrs. Alexander offers to bring him orangeade and cookies – after a somewhat protracted negotiation – he flees before she can return with the goodies, fearing that she is calling the police on him, the way neighbor ladies seem to do. Christopher seems most at ease with the person who understands him best – his teacher, Siobhan. She encourages him to pursue this project and to chronicle the investigation in a book. But she has the good sense to yield to Dad when he forbids Christopher to continue with his investigation and his narrative. With some adorable hair-splitting, Christopher thinks he’s circumventing Dad’s directive as he persists in his probe, getting key info when he meets up with Mrs. Alexander for a second time.

Maybe the niftiest turn of the plot is how Dad ironically entraps himself. By confiscating Christopher’s handwritten book-in-progress, Ed Boone ultimately ensures that his son will not only discover the truth about Wellington but also the truth he’s been hiding about Christopher’s mom, Judy. This section of the plot is bookended by two prodigious meltdowns from Shepherd, the second one stunning enough to remind me of Othello’s fit. Shepherd delivers Christopher’s comical difficulties as vividly as his poignant ones in a performance that rivals his leading role in Hand to God a year ago, but Decker and his design team magnify this performance by working to help us see the action from the perspective of an autistic teen. At the beginning, Decker’s sound design assaults us with loud noises, simulating the sensory overload that is the everyday norm for Christopher. There are similar assaults in Hallie Gray’s lighting design glaring in our faces – and flashing red alarms across the upstage walls when Christopher is tensing up or melting down. We often hear a doglike whimper from Shepherd when he is stressed.

About the only shortfall in Decker’s scenic concept, which opens up Christie’s more enclosed design, is the erosion it inflicts on Jon Ecklund’s projection designs. They just don’t pop as wondrously as they did at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre in New York or at Belk Theater when the tour stopped here in February 2017. We don’t get quite the same amplification when poor Christopher navigates the London Underground or cityscape as he searches for Mum’s flat, and the wow factor when Christopher rhapsodizes on our vast universe is muted. But there was plenty of wattage from Shepherd to compensate, and Becca Worthington gave us more energy on opening night as Judy Boone than I saw on Broadway or at the Belk describing the good times and the bad times before she abandoned her family. By the time she recalled the meltdown at a shopping mall that precipitated her departure, I didn’t require a replay. Afterwards, Worthington gave more of an emphasis on doing better as a mother so it was never overshadowed by her outrage at Ed’s deceptions and misdeeds.

Rob Addison was less wiry and more avuncular than previous Eds that I’d seen, which struck me as good things before and after he was found out. I think first-timers will see Dad’s prohibition of Christopher’s probe as less strict and arbitrary than my first and second impressions were on Broadway and on tour – and that his pleas for forgiveness are sincere and heartfelt. A less cuddly approach to the role is certainly defensible, but I was deeply pleased with Addison’s take. Decker brought Megan Montgomery downstage as Siobhan more often than I remembered, giving Christopher’s teacher slightly more texture than I had seen previously. The brambles in her accent also demonstrated that Montgomery’s years at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland hadn’t been wasted.

An ensemble of six flutters around the four core characters, moving spare scenery pieces around, unobtrusively setting up an electric train set, acting as street and subway crowds, levitating Christopher, and filling multiple minor roles. Tracie Frank and Jeremy DeCarlos stood out as the long-separated Shearses, each abrasive to Christopher in his or her own way. With her nervous gestures and blue-tinted pigtails, Shawnna Pledger’s fussy account of Mrs. Alexander safely transcended that of a generic eccentric. A similar children’s book simplicity hovered over Donovan Harper’s rendition of the arresting Policeman in the opening scene, yet Tom Scott was able to sprinkle some comical discomfort on Reverend Peters when confronted with the question of where heaven is.

Only Lisa Hatt was deprived of a name, portraying a Punk Girl, and a Lady in Street among her various cameos. Decker may have felt sorry for all of Hatt’s unnamed contributions, perhaps allowing her to choose her own number. She was listed in the Actor’s Theatre playbill as No. 40, a radical break from the Broadway and touring company playbills, which listed that role as No. 37. This production certainly paid attention to details! We even had the delight of Stephens’ Pythagorean postscript, which Shepherd dispatched with a full two minutes remaining on the projected digital clock. It was part of a comical meta layer that the playwright sprinkled across Christopher’s dialogues with Siobhan, reminding us that he had adapted Hadden’s novel for the stage. Very successfully, I should add.

It wasn’t long after music director Drina Keen cued the opening bars of Newsies that I already knew. This Disney musical fits the CPCC Summer Theatre program like a glove. Largely fueled by singing, acting, and dancing talent fresh out of college and grad school by way of regional Southeastern Theatre Conference auditions, CP’s youthful summer company is exactly what you want for a story about underpaid New York City newsboys who dare to strike against newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer.

Look at the scaffolding that rises across the stage at Halton Theater, representing the tenements where the raw, gifted Jack Kelly and his fellow newsies are holed up, and you might also suspect that Robert Croghan’s set design measures up well against those of the Broadway production and the national tour. Having seen both, I can add that Croghan’s costumes and Gary Sivak’s lighting also reach those lofty levels. Differences only begin to emerge when the ensemble of paper hawkers starts to dance.

Whether constrained by the limitations of his dancers or the liability limits of CP’s insurance coverage, Ron Chisholm’s choreography doesn’t begin to compare with the high-flying exploits that brought Newsies a best choreography Tony Award in 2012. I found it illuminating to see how that shortfall reverberated through the rest of the production. Music played by the CP Orchestra seemed less vibrant behind more earthbound dancers, draining the Alan Menken score of a bit of its punch. Even the Harvey Fierstein book seemed thinner, plotlines and characters less fleshed-out.

Of course, director Tom Hollis hasn’t trimmed the script, so I’d presume that first-timers may be surprised to discover how mature this Disney product truly is. Sure, the history of the 1899 strike has been tidied up and moved to Manhattan, while the financials are fudged to amp up the drama. Kelly has been installed as the single organizer and leader while Katherine, modeled on an actual newsperson who backed the strike, has been extensively re-engineered, predictably becoming Jack’s love interest.

Jack gets a Jewish newbie named Morris as a sidekick who handles the practicalities of organizing and publicizing the strike, another vague nod toward history; and up in his office, Pulitzer does entice Jack to recant his strike support with a tempting offer. Teddy Roosevelt, then Governor of New York, makes a couple of cameo appearances, adding extra period flavoring, though not nearly as crucial as cousin Franklin was in Annie.

Other factors come into play that could deflect Jack from plunging into full-bore labor agitation. At the top of the show, he and his crippled crony stand on top of their roof, mooning over an escape from the tenements to a cleaner life in “Santa Fe.” Later on, the police raid a newsie gathering and haul Crutchie (what else does a city kid call a crippled crony?) off to jail. Jack feels responsible – and he’s on the lam from the cops himself.

Above all else, our Jack has talent. He could become a visual artist or, more to the point, an illustrator at the newspaper he’s been selling all this time. Jack’s artistic aptitude and the introduction of Katherine are the chief alterations Fierstein makes to the 1992 screenplay by Bob Tzudiker and Noni White. You may shake your head a bit at the end after watching Jack take advantage of both of these exciting opportunities. He’s still waltzing off into the sunset as a newsboy.

With awesome gravity-defying dancing in the jubilant Newsies package, you might easily ignore this gauche resolution, but at Halton Theater, we must fall back on the excellence of Ashton Guthrie as Jack. C’mon, this is all about Jack, isn’t it? Happily, Guthrie delivers. I’ve been watching Guthrie on local stages since high school when he was the evil Zoser in Aïda (from Disney to Disney, right?), and I greeted him back then in 2009 as a triple threat to watch – and keep in Charlotte.

His command of all those skills is fuller now, and the professional polish of his Jack is a constant joy to behold whether he’s speaking, singing, dancing, or simply listening to others onstage. Smoothly, he combines the poise of a natural leader with the roughness of the streets, stirring in the rebellious hormones of a teen. Familiar with much of his past work, I had to chuckle a bit at his pugnacious punk mannerisms.

The elders are so good in this cast that I have to cite them as being the other key reasons why this CP production so enjoyable. Hollis gives every one of these vets free license to give performances that are a wee bit outsized. As Pulitzer, we find that Rob Addison adds a pinch of melodramatic villainy to the brass tacks businessman, and springing off Mount Rushmore as Teddy Roosevelt, Craig Estep adds a Jerry Colonna twinkle to the Rough Rider’s vitality.

Presiding over the newsies’ hangouts, Brittany Harrison and Jonathan Buckner bring us some Big Apple diversity, Harrison as a diva nightclub hostess and Buckner as a deli owner who opens his doors to the boys even when they’re nigh broke from striking. Among the newsie gang, only two pairs of brothers really stand apart to leave as much of an impression as Treston Henderson’s Crutchie. Jalen Walker is just slightly nerdy as Morris Delancey and Patrick Stepp is precociously adorable as little brother Oscar. Collin Newton and Alex Kim are the other bros, Jack’s most enthusiastic boosters and the staunchest militants in his roused rabble.

Looking quite serene and elegant in her prim business attire, Robin Dunavant does get to sketch out a modest storyline of her own, trying to prove that women can be serious journalists long before the suffrage movement prevailed. She’s cool to Jack’s advances at first. Only when she realizes that this déclassé Jack is an upstart labor agitator does she see him as a stepping stone toward professional respectability. And we eventually learn that Katherine isn’t a nobody from nowhere. So that’s why Fierstein has added on Jack’s talents! To justify her affections.

Whatever the right degree of warming up to Jack is required, Dunavant reaches it demurely. She could have turned up the heat a little without endangering Guthrie’s dominance, but this will do.

Is everything pre-ordained by a higher power? Or might everything that happens simply be the inevitable outcome when the algorithms of time and space work upon the star stuff that materialized in the wake of the Big Bang? If not, might a lucky ring or a soothsayer’s gaze into a crystal ball shift the gears of an oncoming fate? These are a few of the notions that Kim Rosenstock was playing with when she conceived Fly by Night, the last musical Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte will ever stage at 650 E. Stonewall Street.

Will Connolly and composer Michael Mitnick joined Rosenstock’s writing team, producing a storyline that revolves around two South Dakota sisters who fall in love with the same New York slacker, Harold McClam, a full-time sandwich maker and songwriter. Daphne and Miriam are as radically different as sisters can be. Daphne is impatient to leave Hill City behind and become a Broadway star, while Miriam is perfectly content to stick around home and pour coffee for the townsfolk at her waitressing job.

But Miriam already is a star in the sense that, listening to her dearly departed dad, she has absorbed the notion, during fondly remembered stargazing sessions, that we all come from that star stuff they were counting in the nighttime sky. Aspirationally, there is a link between Harold and Daphne, who meet first at the clothing shop where she clerks and again across his sandwich counter. Vocationally and temperamentally, Harold has a kinship with Miriam. They spark more instantaneously, more intensely, and more lastingly. Trouble is, they meet at the Brooklyn diner where Miriam works when Harold is already engaged to marry Daphne.

Hovering over the action, as a kind of providential presence with avuncular Our Town overtones, the Narrator frequently shape-shifts into some of the orbiting characters in his tale, including both of the sisters’ parents and the eccentric soothsayer. We actually begin the main story on November 9, 1964, with the funeral of Harold’s mother – exactly one year before his dad’s abortive suicide attempt.

There will be a certain providence in Mr. McClam’s survival, to be sure, but until then, his morose appearances can be somewhat trying and tedious. Each of the three central characters is being tormented by a livelier, more interesting nemesis. Daphne has Joey, a commercially successful playwright who’s getting serious about his craft by writing a play just for her. With plenty of revisions, stretching out the rehearsal process. Harold is bedeviled by the sandwich shop owner, Crabble, a quintessentially cranky New Yorker. The only inkling we get that Crabble has a heart is his chronic hesitation to fire Harold for all his delinquencies and screw-ups.

Miriam has the most important tormentor, that kooky soothsayer who gives her the most improbable set of omens for determining her destined true love, wrapped into a prophecy that promises bliss and catastrophe. All of them begin to recur when Harold walks into her life, sending Miriam scurrying back to South Dakota when the two are on the verge of connecting.

Fleeing fate is no less futile for Miriam than it was for Macbeth or Oedipus. She holds out the hope that her doom isn’t settled until time stands still. That will happen on November 9, 1965 – twice.

Three significant events will happen on that date, only one of them anticipated: the postponed opening of Daphne’s play. Ironically, the only stars shining on Broadway that night will be those that twinkle mockingly in the sky.

With Chip Decker directing and Jerry Colbert narrating, Fly by Night moves along briskly with plenty of verve and heart. Colbert has aged gracefully into the paternal wisdom that the Narrator and Miriam’s dad deliver, yet there is comical extravagance each time he becomes the Brooklyn soothsayer or the South Dakota mom. This Narrator seems to become most personable when he stops the action to guide us into a prefatory flashback, so we appreciate Colbert more and more as these time loops proliferate.

Colbert himself loops back to his heydays, flying by night to some fairly high notes and singing with an ease we haven’t heard from him since, oh, maybe 1997 in the 1940’s Radio Hour. Perhaps he’s inspired or rejuvenated by his co-stars. The sisters, Cassandra Howley Wood as Daphne and Lisa Smith Bradley as Miriam, are aptly cast, already ablaze in their early pair of star songs. Wood repeatedly chants “I’m a star!” with Broadway conviction belting out her anthemic “Daphne’s Dream” as she begins navigating the New York rat race, and there’s a cute Avenue Q silliness to her “More Than Just a Friend” duet with Harold.

Bradley simply torches her calling card, “Stars I Trust,” creating a wider gulf between the sisters than you’ll find on the original cast album, and there’s a greater maturity to her lighter “Breakfast All Day” sequel as she settles into Brooklyn, with less of a shuffling rock beat from the three-piece band directed by Ellen Robison. So easily grooved into a humdrum rut, it’s surprising how unnerved Miriam becomes when the soothsayer sings his “Prophecy” – in two parts – and when her eyes first meet Harold’s. Bradley, Colbert, and Christopher Ryan Stamey make it all work.

Stamey cut his teeth at Actor’s Theatre as their go-to wild man in trashy treasures like Slut and The Great American Trailer Park Musical, so to watch him mellowed into the relatively colorless Harold could be jarring to those who have witnessed his vintage exploits. But he actually nails it as both the nerdy Romeo and the mistake-prone sandwich drone. Best of all, he’s the adult in the room in his ultimate showdown with Miriam, “Me With You,” tapping into who he is and what we all believe must be right in the face of implacable destiny.

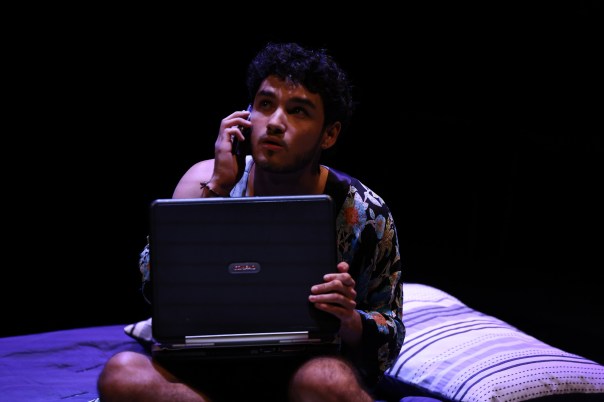

![FLY 4[11]](https://artonmysleeve.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/fly-411.jpg?w=300)

Supporting roles all draw superb performances. Stephen Seay is wonderfully hyper as Joey when he first pursues his muse Daphne in “What You Do to Me” – and still spoiled rotten, revision after revision. James K. Flynn captures the working class vulgarity of Crabble with a poifect accent, combining with Stamey in “The Rut,” a paean to workplace hopelessness and drudgery. Perpetually toting a wee record player and a vinyl recording of La Traviata in his pathological grief, Rob Addison eventually gets to break out of his stonefaced depression as Mr. McClam. Toward the end, he decides to actually go see that opera and later, when someone finally has the time to listen, he pours out his sad, sad love story, “Cecily Smith.” Which just happens to rhyme with one of the best lines of the night: “Who cares what you are listening to? It’s who you’re listening with.”

The design team, Dee Blackburn for the set and Carley Walker for the lights, give us a nice off-Broadway sense of the various locations, efficiently transporting us to Miriam’s yard and front porch in South Dakota, the seedy nightclub where Harold tries out his song, Crabble’s misspelled sandwich shop, and McClam’s bathtub.

When we get to Penn Station and Times Square, however, an SOS goes out to our imaginations. After “At Least I’ll Know I Tried,” a tasty quintet ushering in the eventful denouement, I prophesy you’ll answer that SOS willingly.