Reviews: Nina Simone: Four Women and Ain’t Misbehavin’

By Perry Tannenbaum

With three new theater productions opening last week from Actor’s Theatre, Brand New Sheriff, and Theatre Charlotte – all sporting all-black casts – we have entered a Black History Month in Charlotte that is more about black history than ever before. Some of the African Americans who might be expected to show up for those auditions will be shining in the spotlight somewhere else this weekend as Children’s Theatre of Charlotte opens Bob Marley’s Three Little Birds at ImaginOn.

Unless you count university productions, we haven’t had more than one truly black theater production here in Charlotte during any Black History Month in the past 10 years.

So our Black History Month upgrade – and the stunning amount of local black talent necessary to make it happen – was definitely on my mind as I took in all of these shows. But a couple of times, in Actor’s Theatre’s tribute to Nina Simone and Theatre Charlotte’s Fat Waller revue, I found myself flashing back to January 2003.

That’s when a bi-racial Charlotte Rep production of Let Me Sing featured two black Broadway veterans, Gretha Boston and André de Shields, who boasted five Tony Award nominations and two wins between them.

Nina Simone: Four Women from Actor’s Theatre threw a new perspective on what are usually regarded as Rep’s declining years. The title role, calling for a passionate Black Power advocate and a charismatic singer-songwriter, would obviously benefit from the Broadway star power that Michael Bush, with his Manhattan Theatre Club connections, was able to lure down to our Booth Playhouse during Rep’s latter days.

De Shields was actually one of the original stars of Ain’t Misbehavin’ when it opened at Manhattan Theatre Club and took the Tony for Best Musical in 1978. So my thoughts naturally returned to De Shields, Rep, and Let Me Sing when Theatre Charlotte opened the Fats Waller musical revue two days after Actor’s opened their Simone musical. On this night at least, I had the satisfaction of recalling the Broadway star and feeling that our fair Queen City was getting along just fine without him.

A lot of the credit goes to Charlotte’s own Tony winner, educator extraordinaire Corey Mitchell, who directs this sassy 94-minute show at the Queens Road barn. The cast he culled from auditions is consistently spectacular, whether they’re singing or dancing, but we also need to slice off some accolades to the seven-piece jazz band led by trombonist Tyrone Jefferson, featuring Neal Davenport at the piano. Kudos to choreographer Ashlyn Sumner: with some formidable talents to work with, she has stretched them.

Conceived by Murray Horwitz and Richard Maltby, Jr., Misbehavin’ goes about capturing Waller’s essence by culling the gems from his imposing oeuvre and preserving the pianist’s penchant for interpolating sly comments and wisecracks between his lyrics. Comical gems like “The Viper’s Drag,” “Find Out What They Like (and How They Like It),” and “Your Feet’s Too Big,” all score big. Adapting and orchestrating, Luther Handerson and Jeffrey Gutcheon usually go with the grain of Waller’s merry, mischievous recordings, but occasionally they go against it, slowing down “Honeysuckle Rose” and “Mean to Me” so they sound brand new.

Yet Waller also composed one solemn anthem that belongs in the same elite pantheon as Simone’s “Four Women” and Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.” The introductory chords from the piano were all I needed to tell me that “Black and Blue” was on its way with lyricist Andy Razaf’s indelible refrain: What did I do to be so black and blue?

After delivering more than an hour of pure ebullient joy, it was a powerful question to ask. Lighting designer Chris Timmons dimmed his gels over Tim Parati’s funky nightclub set, Jefferson hushed the band, and Mitchell huddled his entire cast downstage where all five could look us coldly in the eye.

Never afflicted with obliquity. Waller and Razaf answered their own question: My only sin is in my skin.

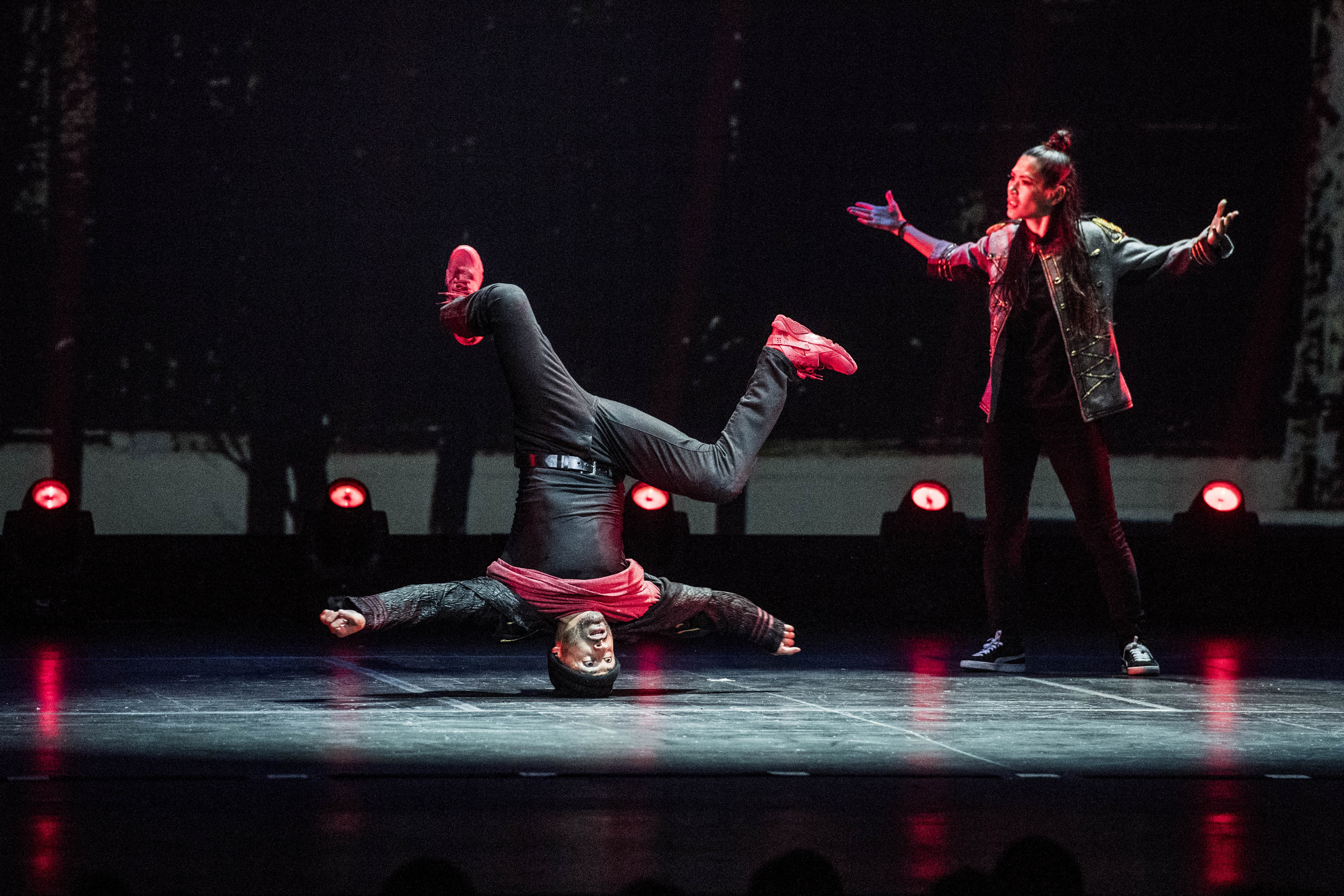

Keston Steele has the most amazing voice in this cast, and it’s not just her range and volume. Steele may look small, but as “I’ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling” proves, this lady can g-g-growl! Best dancer is more of a toss-up. Look no further than Nonye Obichere kicking “How Ya Baby” if you’re looking for somebody startling and athletic. Tyler Smith is your man if your quest is for someone smooth and sensual.

Smith was the comedy showstopper – and the chief reason why De Shields can stay right where he is – delighting us with his stealth and style in “The Viper’s Drag,” but Marvin King was just as hilarious in the outright insulting “Your Feet’s Too Big.” Danielle Burke’s breakout moments were her mellow “Squeeze Me” solo and her bawdy “Find Out What They Like” duet with Steele.

The songlist is loaded with Fats faves that will get your toes tapping, including “Handful of Keys,” “The Joint Is Jumpin’,” “Fat and Greasy,” and “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now.” Or you might get into the sway of “Jitterbug Waltz” and “Lounging at the Waldorf.” All in all, another insane overachievement for Charlotte’s community theater. Pass the reefer and the champagne!

Production values at Hadley Theater looked like they would be up to the usual high Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte standard when we took our seats on opening night of Nina Simone: Four Women. Chip Decker’s set design for the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, is colorful and impressive. And shifty: when Decker detonates his sound design, simulating the bomb blast that killed four black girls on September 15, 1963, the walls twist acutely to register the racist atrocity.

But after Lizzie and American Idiot, two arrestingly loud shows at ATC’s new Queens University home, this Christina Ham drama was often too soft-spoken to be clearly heard – even though I spotted the actors wearing head mics late in the 86-minute performance. That was a major element that can improve as the run continues.

Shortcomings in Ham’s script and Chanel Blanchett’s stage direction are not so easily remedied. I’m sure the playwright didn’t intend to be insulting, but her scenario basically tells us that Simone went down to the 16th Street church, stationed herself defiantly behind the sanctuary keyboard with the intention of completing her livid protest song, “Mississippi Goddam.” While completing her response to the murder of Medgar Evers three months earlier in Mississippi, three of the women who would be immortalized in “Four Women” walked in off the street to take refuge from the violence still raging out on the streets of Birmingham.

Fate basically hands the songwriter one of her most revered compositions, if you take Ham literally.

I’m not sure that Blanchett wants us to take the story that way. Played with stormy intensity by Destiny Stone, Simone is already hostile and militant when she arrives in Birmingham. Nina’s urgent need to get her song finished only begins to catalog the reasons why she antagonizes each of the three women who walk in on her. Sarah is a humdrum housemaid who would rather pursue MLK non-violence than take Malcolm X action. Sephronia is a yellow-skinned socialite who doesn’t struggle at all financially like Sarah, drawing class hatred from the housekeeper for her money and scorn from Simone for her political aloofness.

Further stirring the pot is Sweet Thing, seething because she can’t have Sephronia’s fiancé though she can have his baby. This liquor-swigging streetwalker draws hatred and scorn from all quarters, for how she lives and for entering a holy place. Beware, though, she’s brandishing a knife.

Although the arguments are passionate, Blanchett blunts their sharpness, preferring to space her players rather than getting them in each other’s faces – until Arlethia Friday arrives as Sweet Thing. Stone, Erica Ja-Ki Truesdale as Sarah and Krystal Gardner as Sephronia often face us instead of the person they’re arguing with. Maybe Blanchett doesn’t really believe that Simone and the “intruders” are really there at the Baptist Church. Having these actors appear like they’re reliving the first play they ever performed in grade-school doesn’t solve the problem.

After all the verbal and physical combat, the title song breaks out. It’s surreal: all three women miraculously know their lyric and their order in the song. I’m guessing this dramatic flouting of logic will help distract us from the fundamental flip she burdens Stone with in portraying Simone. For 80 minutes, she has heaped hatred, anger, and scorn upon these women who are interfering with her creative process. Now she’s deeply empathetic toward them all, turning them into emblems of scarred, heroic black womanhood.

With 11 other songs along the way, there are sudden lurches as we move forward, cutting abruptly from argument to song. Stone’s singing, with pianist Judith Porter leading a driving quartet, is the show’s most human element as she channels Simone’s fire into “Sinnerman,” “Mississippi Goddam,” and the last of the “Four Women.” Stripped of the backup singers that sugarcoat Simone’s recordings of “Young, Gifted, and Black,” I liked the crispness of Stone’s even better.

Intensity was never Stone’s problem. What I was looking for was more arrogant self-assurance lifting her rage to a higher plane – a serene majesty that earns you the title of High Priestess of Soul. A few more leading roles, not to mention turning 30, will likely do the trick someday. Probably because she comes in toting a flask and a knife, getting the liberty to stagger around the stage rather than finding a mark and facing front, Friday’s Sweet Thing is the best acting we see. She isn’t Simone’s Sweet Thing until she sings her, but she’s closer to what Nina had in mind than Ham’s housemaid. Darting between the worlds of rock, jazz, blues, folk, and soul, Simone has eluded many who would find excitement and enjoyment in her music. Ham’s writing marshals key facts in this North Carolina native’s life into the dialogue but never really captures her soul. The songs in Four Women and Stone’s singing could be a gateway to that treasure trove.