Review: The Drowsy Chaperone at Theatre Charlotte

By Perry Tannenbaum

My advice for best enjoying The Drowsy Chaperone at Theatre Charlotte is to listen to the Man in the Chair – and yield to his pitch-dark hypnosis. Yes, before the lights even go up at the old Queens Road barn, he’s in his chair speaking to his audience and conjuring up what we should hope and pray for: “I just want to be entertained. Isn’t that the point?”

As the show unfolded, brilliantly directed by Billy Ensley with what must be the local cast of his dreams, I realized that, as a critic, I shou

ld heed that hypnotic suggestion devoutly. Discard my usual pointy critical and analytical tools. What’s more, I came to believe more and more strongly that, if actors and directors of previous Drowsy Chaperones I’d seen had followed that simple mantra, I would have fallen in love with the show long before last Friday night.

When the lights came up a few minutes deeper into the Man in Chair’s monologue, we saw him locking the front door of his humdrum apartment with four or five assorted deadbolts and chains. It’s a bit of an abrupt swerve, but we’re suddenly aware that this Broadway musical devotee is a recluse and a bit paranoid. Each time the phone rings, we’ll see that the Man in Chair fails to answer, yet another confirmation of these traits.

By the time the title character of the fictional “Drowsy Chaperone” is a few wobbly notes into her showstopping “As We Stumble Along,” we already should know that the Man in Chair is gay, which accounts for Lisa Smith Bradley delivering the song as a living fetishization of Ethel Merman and Judy Garland – Merman’s vibrato wedded to Garland’s glitter, slacks, and drug dependency.

Yet when we’re watching Kyle J. Britt as our genial host, we need not attribute his reclusiveness or paranoia to being a gay man. As a Broadway musical fanatic, this Man in Chair identifies more readily as a New Yorker with Innerborough hangups. Meanwhile, Bradley is sufficiently over-the-top as both gay icons – especially Merman – to be accused of impersonating a female impersonator.

We might say that Ensley & Co. have decided that being gay in 2024 isn’t nearly the leaden weight it was in 2006 when Drowsy Chaperone premiered in the Big Apple or in 1996 when Angels in America tore the QC apart and made us a laughingstock. Pretentiousness, solemnity, and subtlety really are inimical to this delicate relic. Britt handles it with audiophile care as removes the vinyl disc – a rare original cast recording of his favorite 1928 musical – from its LP sleeve and gives both sides a loving once-over with a Discwasher brush before lowering his treasure onto a turntable.

The same can be said of size and scale, which may also have muffled my enjoyment of productions at Belk Theater in 2007 and Halton Theater. There’s something so right about our little séance in the dark at the Old Barn on Queens Road that it cannot attain in a more modern and spacious hall where the Man in Chair must project his spell into a distant balcony. The homeliness of the Man’s urban dwelling also sits better on Queens Road than in the bowels of a bank building on Tryon Street.

To be honest, it’s Broadway Lights and the late CP Summer Theatre that should apologize for not matching the unpretentiousness of Josh Webb’s scenic design. Of course, it would be nice if Webb’s scenery could transform spectacularly into Broadway splendor when the stylus of our host’s turntable comes down – with its signature thump – onto the vinyl and the mythical “Drowsy Chaperone” comes to life. In the less-is-more world on Queens Road these days, these shortcomings are comedy assets, part of the overall charm.

On the other hand, our time travels to 1928 get a softer landing thanks to the costumes by Beth Killion, notable for their flair, their formality, and their discreet dashes of color. We’re awaiting the wedding of Robert Martin and Janet van de Graaf, so there are actually multiple levels of time travel here, for Bob Martin actually co-wrote the Drowsy Chaperone book with Don McKellar – and starred in the original Broadway production as Man in Chair – while he was married to the real-life Van de Graaf.

In fact, this originally Canadian work, which eventually layered on music and lyrics by Lisa Lambert and Greg Morrison, was gestated at Martin’s stag party in 1997, nearly 70 years after these fictional nuptials. More reasons not to view this lark as a gay cri de cœur.

Rare as his vinyl treasure may be, Britt comes across less as a scholar or a critic than as a fanboy, occasionally panting like an eager puppy as he presumes to approach his fantasy idols more and more closely. More than once, the principals will obligingly freeze for him. Nor does this Man in Chair seem to favor the men over the ladies with his adoration, only tipping the scales just before the final bows. Charmingly enough, there are overtones of scholar and critic as he dishes tasty trivia about the fictitious “Drowsy” cast members or advises us to be on the lookout for some truly dreadful lyrics.

These glamorous, theatrical, servile, and criminal characters are all blissfully ignorant of the nerd who has conjured them up, preoccupied with their conflicting efforts to carry off the planned wedding or ruin it. The bride herself, Lindsey Schroeder as Janet, seems to be grandly ambivalent about becoming Robert’s wife, sacrificing her glittery stage career and the adoration of millions, while suppressing her basic instinct to “Show Off.” Love is at comical war with vanity. Carried away by the swiftness of this whirlwind romance, Andy Faulkenberry as Robert also has his doubts.

Aside from Janet’s drunken chaperone, politely labelled as Drowsy, there are a butler Underling, an eccentric Mrs. Tottendale, and Robert’s best man George shepherding the loving lambkins to the altar. Only Zach Linick as George seems to be afflicted with any degree of competence or reliability. More importantly, he and Faulkenberry make up a formidable tapdancing duo. (Thank-yous to choreographer Lisa Blanton.) Allison Rhinehart as a frilly, bustling Tottenham and Darren Spencer as the gray and starchy Underling are no less inevitably channeled toward blithe entertainment.

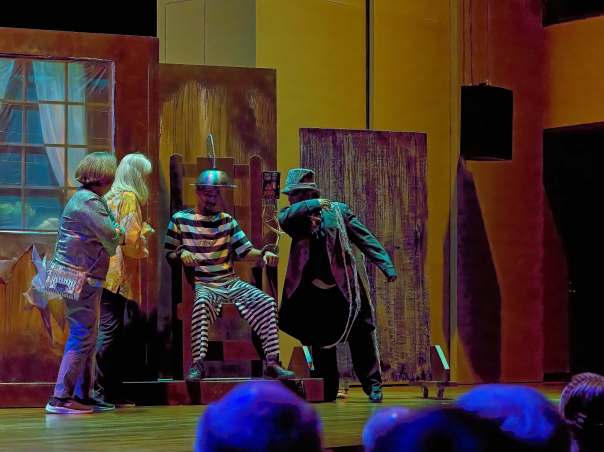

Counterbalancing the fragile determination of the bride and groom, compounded by the flimsy protection of their good friends, we have an exquisite mix of bumbling baddies trying to sabotage the wedding. These are led by Joe McCourt as Broadway producer Mr. Feldzeig (Feldzeig Follies ring a bell?), under pressure from his mobster backers, who consider Janet to be the cash cow of the Feldzeig franchise. The sneering McCourt is bedeviled by Gangster 1 and Gangster 2, armed emissaries – Titus Quinn and Taylor Minich – masquerading as hired chefs to ensure a catastrophe.

Ah, but it isn’t simply muscle aimed at swaying the maiden and returning her to showbiz. Somehow, a predatory Lothario is among the wedding guests – although he has never met anyone else there. Mitchell Dudas is this egotistical Adolpho, far more arrogant than Feldzeig, a mixture of Erroll Flynn and Bela Lugosi with a thick Iberian accent. Feldzeig has no trouble at all convincing Adolpho that he was born to seduce the bride-to-be.

Equally dumb, Autumn Cravens as Kitty is a ditzy chorine, constantly nagging her boss and wedding escort Feldzeig to let her fill Janet’s shoes in his next Follies. Effortlessly, Dudas will outperform Cravens in thwarting Feldzeig’s schemes. Love conquers all, but it would be a huge spoiler to say how many times when we reach this very happy ending.

Just one more wild card is needed to tie up all the festivities. Be on the watch for Trinity Taylor as Trix the Aviatrix, who descends from the skies at just the right moment with a voice of thunder. For a few moments, she even upstages Britt and Schroeder who are so fabulous.

It would be a mistake to miss the craftmanship lavished on this plot with its stock characters by Martin and McKellar, brought out so brilliantly by Ensley and his dream cast. For instance, think how perfectly 1928 was chosen: between Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight, Babe Ruth’s 60 homers, The Jazz Singer of 1927 and the Wall Street Crash of 1929. A brief last window of bliss before global misery. In the real world, the parade of yearly Ziegfeld Follies revues would be halted after 1927 – until 1931.

![IMG_4165[1]](https://artonmysleeve.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/img_41651.jpg)

The three Heathers retain their iconic croquet mallets from the film, but costume designers Beth Killion and Ramsey Lyric get Griffin’s drift and take their outfits in a more dominatrix direction. Together in various synced poses, they are sensational — all in major roles for the first time.

The three Heathers retain their iconic croquet mallets from the film, but costume designers Beth Killion and Ramsey Lyric get Griffin’s drift and take their outfits in a more dominatrix direction. Together in various synced poses, they are sensational — all in major roles for the first time.