Review: Meet and Greet at The VAPA Center

By Perry Tannenbaum

Auditions are a kind of interview, and interviews are a kind of audition. You enter, drop a résumé on somebody’s desk, and minutes or hours later, you exit elated or deflated. Instant drama. Singularly human. A paradigm of life.

At the VAPA Center, auditions and interviews are the entire evening for three weekends in Meet & Greet, a themed set of three one-act comedies produced by Charlotte’s Off-Broadway in the COB Black Box. Yeah, from the outside looking in on aspirants and applicants who have stressed for weeks preparing, strategizing, dressing, and grooming for the big moment or trial by ordeal, the denouement can be quite entertaining.

We can laugh our heads off at these overinvested humans and empathize at the same time. Imagining we were them or grateful that we are not.

Of course, there are perils for playwrights working within these familiar templates. Skirting predictability is the keenest, particularly if your audience has been exposed to sketch comedy over and over.

You can rest assured that each of the playwrights featured at VAPA contrives to make the familiar ritual different from what we expect, concealing at least one twist and surprise. Neither Susan Lambert Hatem’s Hamilton Audition nor Don Zolidis’s The Job Interview far exceeds the length of a typical TV sketch, so opinions will likely vary on whether they transcend the streaming standard.

Both of them have yummy roles for multiple players, so transcendence becomes less of a factor if you’re seeking comedy simply for escape in these dark days. The incontestable headliner of the evening is the finale, Meet & Greet by Stan Zimmerman and Christian McLaughlin – in terms of length, number of histrionic roles, and prestige. Zimmerman’s fame rests chiefly upon his extensive writing credits, most notably the beloved Gilmore Girls and The Golden Girls.

Meet & Greet clocks in at more than twice the length of most sitcom episodes. Between laughs or afterwards, you may catch yourself pondering why.

COB’s producing artistic director – and VAPA Center co-founder – Anne Lambert has her energetic hands all over this one-act hodgepodge, starring as The Director in her sister’s Hamilton Audition and (what else?) stage directing all that follows.

There may be an inside joke here. Do you really audition for the role of The Director in the play you have programmed by your sister at your own theatre? Do you think director Anna Montgomerie invited Lambert to play the role, or was the inviting done in the opposite… direction? Wouldn’t Lambert, not the shyest person on the Charlotte theatre scene, have leveraged some of her status – and experience – in determining how her character should be written and played?

We’ll never know, unless the saga of putting Hamilton Audition on its feet spawns another script. In the present instance, Lambert has invited the most prodigious voice in town to audition for the lead role in an all-female production of Hamilton, and the diva who has graciously consented is apparently the only person on the planet who has never heard of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s megahit.

More likely, people who come to see Hamilton Audition will not realize that Lambert was a co-founder of Chickspeare, which pioneered all-female productions of Shakespeare in the QC. It is not at all far-fetched to say that Lambert inspired the role she is playing as well as the play her sister has written. Posters on the rear wall touting fictional Chickspeare productions practically shout this in-joke out loud.

From appearances, you might conclude that Lambert is more out of her element directing a hip-hop musical than Nasha Shandri as Shondra Graves is auditioning for the role of Aaron Burr. Just you wait. Although she looks perfect for her dashing Founding Father role, Shondra gives a more atrocious hip-hop reading than you would dare to expect from The Director.

Comedy gold.

Amazingly, Shandri is supposed to be no less ignorant about rap than she is of Hamilton! Suddenly, the whole idea of a pioneering all-female version seems like a certain disaster… with fallout for females and minorities. It’s at this point that Graves and The Director probe the sexism that already lurks in the original gendered Hamilton. So yes, Hatem has put some meat on her hambone dialogue.

Whether or not Zolidis replicates that feat in The Job Interview is more open to question. The bio in the digital program, summoned by your QR code reader, states that Zolidis is one of the most prolific and produced playwrights in the world. Maybe the thuddingly generic blandness of this title explains why Zolidis was so previously unknown to me nonetheless.

Fortunately, his Job Interview playscript proves to be livelier and more imaginative. The basic premise, we will soon find, ensures that the sparks will fly. Both of the applicants waiting to be called into T.J.’s office, Chloe Shade as Marigold and Marla Brown as Emily, will be interviewed at the same time, adding the elements of confrontation and fierce female competition to the drama. For Emily, it’s already life-or-death.

If you’ve inferred that T.J. is eccentric and perhaps sadistic, you’re on the right track. Rahman Williams as T.J. doesn’t ask his applicants a scripted set of questions – or even the same questions. Deepening his aggression and moving us abruptly from interview to audition, he challenges Marigold and Emily to show him how they would handle specific on-the-job situations.

Not only might we say that the difficulty of the questions and roleplay challenges seems to be tipping the scales of fairness way off kilter, but we can also discern radical differences in the temperaments and preparedness of the two candidates. It would be impossible to find an aspect of Emily’s performance where she outscores her rival… aside from how desperately she needs this.

Now anybody interviewing for a job knows that he or she is already facing steep odds, but knowing that you’re outclassed during the interview is a special torture, one that permits Brown to go totally nuclear as Emily. On the other hand, Shade can play with the absurd and ballooning insult that Marigold, in all her perfection, is obliged to keep competing with this loser – and that the outcome still lies in the hands of this outrageous interviewer.

Rahman, in the meantime, gets to play with the disconnect between T.J.’s spit-and-polish military background and his high-level position at Build-a-Bear Toys. Three tasty roles, all well-done. During the run, Nicole Cunningham shares Shade’s chores.

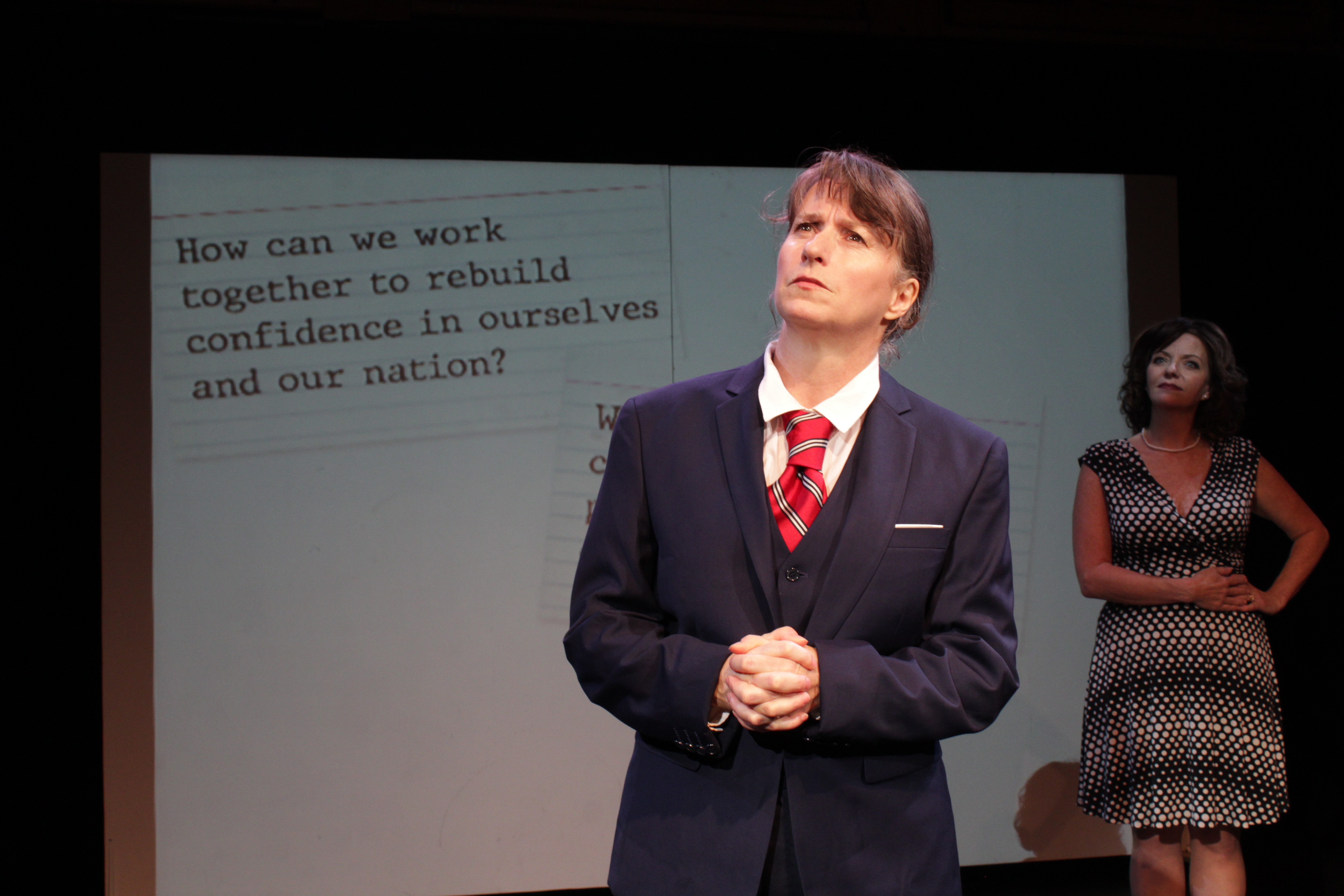

Contrary to what you may be thinking while it plays out, Zimmerman & McLaughlin have aptly named their Meet & Greet. Take it in the same way that the four auditioning actresses do and ride the rollercoaster. To make it all tastier, two of the four have a history together, co-starring long ago during better days on a hit sitcom, Lane Morris as the embittered psycho Belinda and Stephanie DiPaolo as the bimbo Teri.

For my generation, I was thinking Joyce DeWitt and Suzanne Sommers from Three’s Company, but you might hear different echoes. Teri is the airhead who tends to spoil everything, or she is deeply misunderstood and cruelly typecast. Bubbling and pouting seem to be her main forms of expression. Also in the room before Teri’s majestic entrance is Marsha Perry as Desiree White, with some sort of acting experience as the star of the “Real Housekeepers of Palm Beach” reality show.

Contrasting nicely with Desiree and her leopard-skin bodysuit is Joanna Gerdy as the splendiferously monochromatic Margo Jane Mardsden, who has fallen from her regal perch as living Broadway legend due to a combo of drink and disgrace. Being among this gaggle, especially the déclassé Desiree, is already a devastating humiliation.

Yet as we can hear as they emerge from their auditions, both Desiree and Margo are spectacularly successful in their auditions for the role of Andrea, the leading lady of an upcoming series pilot. Leopard Skin draws uproarious laughter from the sanctum within before Diva Nun draws a thunderous ovation. Which one do the showrunners, producers, and writers inside actually prefer?

Every word that Tommy Prudenti utters as the Casting Assistant is a tantalizing clue to what the show and Angela will be, and there is a girlish coyness about him… and a deceptive servility. All through this epic catfight showdown, Zimmerman’s Golden Girls pedigree is on display in a blizzard of quips, taunts, and one-liners. We shall only divulge the maestro’s recipe for “sidewalk pizza” here: you jump out the window of a tall city building.

Yes, I’d advise doubling and tripling the roles of the staffers. Then Josh Logsdon would have more to do than Mondale’s brooding fatalism, the criminally underused Berry Newkirk could more fully display the full spectrum of his talents, and Paul Gibson as Jordan could flub a more interesting variety of lines. That tack would also present ways of sneaking in more background info about 1979 America and let us outside of the White House West Wing bubble that Hatem creates. With those enrichment opportunities missed, Greg Paroff as Hertzberg, both avuncular and ambivalent, emerged as the most compelling performer in a supporting role while Nathaniel Gillespie was convincingly cringeworthy as Caddell.

Yes, I’d advise doubling and tripling the roles of the staffers. Then Josh Logsdon would have more to do than Mondale’s brooding fatalism, the criminally underused Berry Newkirk could more fully display the full spectrum of his talents, and Paul Gibson as Jordan could flub a more interesting variety of lines. That tack would also present ways of sneaking in more background info about 1979 America and let us outside of the White House West Wing bubble that Hatem creates. With those enrichment opportunities missed, Greg Paroff as Hertzberg, both avuncular and ambivalent, emerged as the most compelling performer in a supporting role while Nathaniel Gillespie was convincingly cringeworthy as Caddell.![CATS cast photo + Anne + Susan #1[4]](https://artonmysleeve.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/cats-cast-photo-anne-susan-141.jpg)

![3Days-ART[8]](https://artonmysleeve.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/3days-art8.jpg)