Review: Spoleto Festival USA in Charleston

By Perry Tannenbaum

Looking down benignly at his Dock Street Theater audience, the newly anointed host of Spoleto Festival USA’s chamber music series, Paul Wiancko, gave us a slight ceremonial nod. “You have chosen wisely,” he said sagely.

But he wasn’t exactly speaking to me, since this was already the fifth program in the noonday series – the backbone of Spoleto – that I was attending this year. Nor was he speaking to the “eleven-ers” in the audience who were signed up for the complete set of programs down in Charleston through June 9.

He was speaking directly to those in the audience who would only attend one of the concerts. Today. And he would go on to ask us all to participate in making the experience special and unforgettable.

It would be very special – beginning with a Beethoven piano trio that showcased Amy Wang at the keyboard, Benjamin Beilman on violin, and Raman Ramakrishnan on cello. How’s that for diversity? My love affair with Wang’s artistry and demeanor had begun just two hours earlier when she played the Schumann Violin Sonata, teamed up with the Slavically expressive Alexi Kenney.

Enough to mightily crown most concerts, the Beethoven was merely a satisfying appetizer. For Wiancko had cooked up a powerful combo, calling upon two living composers that I was barely familiar with, Jonathan Dove (b. 1959) and Valentin Silvestrov (b. 1937).

Our contribution to the magic would be to withhold our applause between the two pieces. It was easy enough to maintain stunned silence after In Damascus, Dove’s heartfelt setting of Syrian poet Ali Safar’s grieving – and aggrieved – reaction to a senseless car-bombing in his nation’s war-torn capital.

The prose poems were achingly and angrily sung by tenor Karim Sulayman, perhaps most indelibly after an extended instrumental interlude, turbulently delivered by a string quartet that included Kenney, Beilman, Wiancko (on cello), and violist Masumi Per Rostad.

“We will be free,” Sulayman sang in Anne-Marie McManus’s ardent translation, “of our faces and our souls – or our faces and our souls will be free of us. And the happy world won’t have to listen to our clamor anymore, we who have ruined the peace of this little patch of Earth and angered a sea of joy.”

Sulayman was visibly in tears as the lights went down on In Damascus and pianist Pedja Mužijević entered with his iPad and sat down at the Steinway. In the dimness, Mužijević played Silvestrov’s Lullaby, an appropriate coda to a song sequence that began with the children of the Zuhur neighborhood in Damascus who would never wake from their sleep – or survive a bogus “holiday truce” – and ended with the evocation of mothers and loved ones who would always await their return.

Amazingly enough, this isn’t the only instance where Sulayman is singing about children caught in the web of brutal war and barbaric terror, for his wondrous voice also figures at Spoleto in the world premiere of Ruinous Gods, a new opera with exotic music by Layale Chaker and libretto by Lisa Schlesinger.

Co-commissioned by Spoleto, Nederlandse Reisopera, and Opera Wuppertal, Ruinous Gods is a fantastical deep dive into the mindworld of Uppgivenhetssyndrome, a rare traumatic response to living in the limbo of displacement. It was first observed in children detained in Sweden, but the syndrome has now been observed in refugee camps around the world. Hopeless children simply go to sleep in reaction to their endlessly unresolved status. Some die, others lapse into coma – sustained only by a feeding tube.

Encased in a surreal bubble over a grassy bed from scenic designer Joelle Aoun, that is how we find our sleeping-beauty protagonist, Teryn Kuzma as H’ala, when the opera begins. Mezzo-soprano Taylor-Alexis DuPont as her mom, Hannah, is stressing and blaming herself while two doctors, Overcast and Undertow, hover over their patient, unsympathetic researchers hoping to analyze and classify the disease.

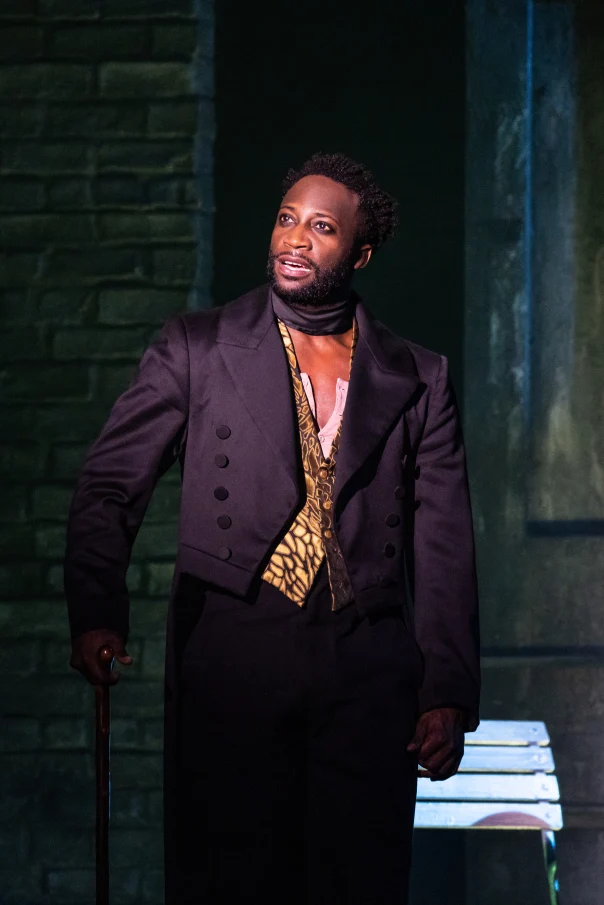

Meanwhile, Sulayman is decked out in a feathery all-black outfit as Crow, the mentor who, like Dante’s Virgil, guides all these comatose children from around the globe into a common underworld dreamscape where all are free. Is that a spaghetti rainbow dropping down across the Sottile Theatre stage from the fly loft as the imprisoning globule lifts off H’ala, or is there an unfathomably large jellyfish floating above?

Sinuous, jazzy, and sensuously obsessive, Chaker’s music resurfaced in the jazz sector of Spoleto 2024 – at Charleston Music Hall, a venue never used by the festival before. Bigger than Spoleto’s customary hall for chamber jazz (and eccentric modern music), the Emmett Robinson at the College of Charleston, the Music Hall was an acoustic revelation and a welcome escape from the Robinson’s clean-room sterility. Bonus points for the stars that lit up on the black backdrop.

Attendance was astonishing, more than could ever be seated at the Robinson, as Chaker, leading her Sarafand quintet on violin – with an occasional vocal – delved into her two most recent albums, Radio Afloat (2024) and Inner Rhyme (2019). Having worked with Daniel Barenboim and his West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, Chaker has created a jazz equivalent in Sarafand with Phillip Golub on keyboards, Jake Charkey on cello, John Hadfield on drums, and Sam Minaie behind the bass.

Compared to her opera, Chaker’s jazz and her Sarafand personnel made subtler political points. But this wasn’t the only jazz gig that came loaded with extra cargo. Terri Lyne Carrington returned to Cistern Yard for a pointedly themed concert under the moon and the live oaks – with political firebrand diva (and NEA Jazz Master) Dianne Reeves as her special guest.

Carrington’s cargo was collected into her Grammy-winning album of 2022, New Standards, Vol. 1, the first studio sprouting of her pathfinding songbook collection, New Standards: 101 Lead Sheets by Women Composers. So without much preaching, her set was a celebration of Geri Allen, Gretchen Parlato, Eliane Elias, and – at a high summit where Reeves duetted for the first time with Christie Dashiell – the great Abbey Lincoln and her mesmerizing “Throw It Away.”

All these greats joined together again on Allen’s “Unconditional Love,” with Kris Davis on piano, Matthew Stevens on guitar, and trumpeter Etienne Charles all getting in their licks, plus spoken and dance stints from Christiana Hunte. Wow.

Theatre at Spoleto this season is densely messaged. Or not. The Song of Rome was deeply immersed in issues of immigration and sexism, with an overarching interest in the fate of republics, in ancient day Rome and 21st century USA. Cassette Roulette, on the other hand, was pure frivolity, barely deeper than its title and whole lot bawdier.

After starring in An Iliad last season, Denis O’Hare could be logically expected to follow up that one-man conquest with An Odyssey. Well, he has, sort of. O’Hare co-wrote A Song of Rome with Lisa Peterson, his Iliad writing partner, but this time he doesn’t appear onstage, handing over the acting chores to Rachel Christopher and Hadi Tabbal.

Christopher is Sheree in modern times, a grad student striving to learn Latin, and Octavia, Emperor Augustus’s sister at the dawn of the Roman Empire. Tabbal is Azem in present day, Sheree’s immigrant Latin tutor – and our overall storyteller – and the poet Virgil during the reign of Augustus.

So O’Hare is skipping over the rest of Homer to engage with Rome’s great epic, The Aeneid, knowing full well that Virgil based the first six books of his masterwork on The Odyssey and the last six on The Iliad. As a thematic bonus, O’Hare and Peterson discovered during their research for this world premiere that Virgil himself was a refugee, forced out of his ancestral home in Northern Italy by Roman avengers of Julius Caesar who got Dad’s estate for their prize.

Although Virgil’s epic was likely commissioned by Emperor Augustus, aka Octavian, doubt remains whether The Aeneid is a work of propaganda justifying the Roman Empire as divinely ordained – tracing Octavian’s ancestry back to Aeneas and Venus as meticulously as the New Testament traces Jesus back to King David, son of Jesse – or a subversive work by an immigrant genius settling a score. While getting handsomely paid to do it.

Octavia and Virgil go back and forth on this point because the Emperor’s sister is both an admirer and a keen reader, but both are critical of Octavian, who is hell-bent on buttressing the legitimacy of Rome while closing off its path back to a glorious Republic.

“The Republic is over,” they agree. And how about ours?

While Sheree is learning about the Roman issue that comes up as Virgil delivers more and more manuscript pages to Octavia over the years, Sheree must face the issue in American terms when Azem receives a deportation notice. Does she instantly jump to his defense and rescue, or does she immediately suspect him of criminal activity?

Meanwhile, Sheree is reading The Aeneid differently from Azem and Octavia. Why is Octavia left out of literary history if she played such a key role? Why are Virgil’s women, particularly Dido and Lavinia, so passive and pathetic while the strong woman, Camilla, is a she-devil?

Finding this insidious neglect and defamation rampant in literary history and beyond, Sheree comes up with a radical, shocking solution that she announces on her podcast. She will pour fuel over every single book piled on the Dock Street stage and burn them all.

When will all this vicious animosity end? Citing the end of Virgil’s epic, where Aeneas, the immigrant from far-off Troy, killed the vanquished Turnus instead of offering peace, conciliation, and mercy, Sheree answers us curtly lighting the flame: it won’t. Opting for chaos, she almost says it aloud – to hell with the immigrants. (Or give it to the immigrants, if you’ve heard of the Goths.)

Moments like that land hard at Spoleto. Deep in Trump Country, at the Sunday matinee of Ruinous Gods, there was a loud boo among all the lusty cheering as the singers took their bows. Good. The nurturing point of the opera, gushing with empathy toward immigrants worldwide, had hit home, no matter how you feel about it.

Depending on whether you were attuned to John Cameron Mitchell’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch cache, or whether you resonated with Amber Martin’s worship of Reba McIntyre, Bette Midler, and Stevie Nicks, Cassette Roulette was hit-and-miss, redeemed or further cheapened by Martin’s bawdiness. Nicks’ “Rhiannon” was the crowd fave and mine on the night I attended, getting a far more epic performance that you’ll hear on AM radio or an elevator. But neither David Bowie nor Midler got much of a rise. The diet of ‘70s and ‘80s hits didn’t draw much of a youth crowd to Festival Hall, which was made over to a quasi-cabaret setup.

Trombone Shorty slayed far more decisively at TD Arena, where his outdoor revels with Orleans Avenue were abruptly moved when rain threatened. At the height of the indoor bacchanale, Shorty paraded through the audience at the home of College of Charleston basketball with key members of the band (none of whom were named in Spoleto’s fabled program book). They slashed up the rear aisle of the stadium, swung around to the side of the gym and came down along the side.

Snaking through the stadium, Shorty & Orleans reigned over the reigning pandemonium. The prohibition against photography was washed out to sea in a riptide of glowing cellphones.

Shoot, the band was taking selfies! And through it all, the sound remained perfect, Shorty and his brass perfectly aligned with the rhythm section on the TD stage, absolutely distortion-free. Sure, a few dissenters and defectors also trickled through the aisles, accompanied by true believers seeking and returning with beverage.

The most pathetic sufferer sat right across the aisle from my wife Sue and me, hunched over, elbows on kness, with his hands tightly cupped over his ears. Probably needed a ride to escape. Maybe he would have fared better in the open air, where at least some of the sound could have escaped skyward through the live oaks of Cistern Yard.

Final week highlights: Bank on it, the Bank of America Chamber Music series has four more different programs to offer – and a dozen performances – before Spoleto wraps up on Sunday. The Wells Fargo Jazz lineup continues strong, with an all-star Latin twist. Puerto Rican saxophonist Miguel Zenón and Venezuelan pianist Luis Perdomo bring their Grammy-nominated El Arte Del Bolero albums to life at the Dock Street Theatre in a three-day, five-performance engagement (June 6-8) while Cuban percussionist extraordinaire Pedrito Martinez lights up Cistern Yard with an Afro-Cuban stewpot of infectious rhythm, Echoes of Africa (June 7).

After distinguishing themselves in Mahler’s Fifth, the Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra returns to Gaillard Center with Beethoven’s Third (June 5), plus a Rachmaninoff concerto for piano + trumpet and composer-in-residence Reena Esmail’s “Testament” for tabla and orchestra. Upstaged by a visitation from the Charles Lloyd Sky Quartet this past weekend, the Spoleto Festival USA Chorus rebounds with a two-performance run of The Heart Starts Singing (June 6-7), sporting another Esmail piece that will feature Wiancko’s cello – and an eclectic mix of works by Tomás Luis de Victoria, Rachmaninoff, Irving Berlin, and more.

The Festival Finale of yore is gone this year, but there’s more folk, funk, Americana, and alt-country in this year’s Spoleto lineup. Still to come are Andrew Marlin and Emily Frantz’s latest partnering, Watchhouse (June 5), with their own band-backed experiments in folk-rock playing at Cistern Yard; Grammy Award winner Aiofe O’Donovan (June 7) returns with the SFUSA Orchestra to Sottile Theatre; and Jason Isbell (June 8-9) headlines the final weekend with a two-night stint at the Cistern.

Theatre continued during Spoleto’s second weekend with sharply contrasting shows, the wholesome Ugly Duckling from Lightwire Theater and the savagely satirical send-up of the American West, Dark Noon, from the Danish fit + foxy company in its US Premiere. A similar dichotomy prevails this week as Australian company Casus Creations takes over Festival Hall with Apricity (June 6-9), a family-friendly mix of aerial and acrobatic astonishment, with sprinklings of comic shtick and moody music.

On the edgy side, RuPaul’s Drag Race fans can rejoice greatly as Season 9 champion Sasha Velour deigns to bring her presence to Gaillard Center with The Big Reveal Live Show! (June 6). Is Charleston’s big house big enough for drag’s Queen of Queens? The Holy City and Spoleto haven’t been so sensationally desecrated since Taylor Mac ruled the festival.