Review: One Year to Die at Matthews Playhouse

By Perry Tannenbaum

September 11 has been part of LaBorde family lore much longer than for nearly all other American families. On that date in 1943, the USS Rowan was sunk in Mediterranean waters by German torpedoes after delivering an arms shipment to Italy to combat the Nazis. Local actor/director/playwright/school principal Charles Laborde’s Uncle Joe was among those aboard the Navy destroyer lost on that day, along with 201 other officers and crew. Only 71 survived the attack, rescued by the USS Bristol.

Curiously enough, the official date of Uncle Joe’s death is listed as September 12, 1944 – still a full five years before Charles was born – because none of those 202 bodies was recovered. As the Naval Officer informs Charles’s grandma Edwina with full-dress formality in LaBorde’s new play, One Year to Die, Joe was officially “missing” after the Rowan was torpedoed until one year and one day had elapsed. Then the Naval Death Certificate would be issued.

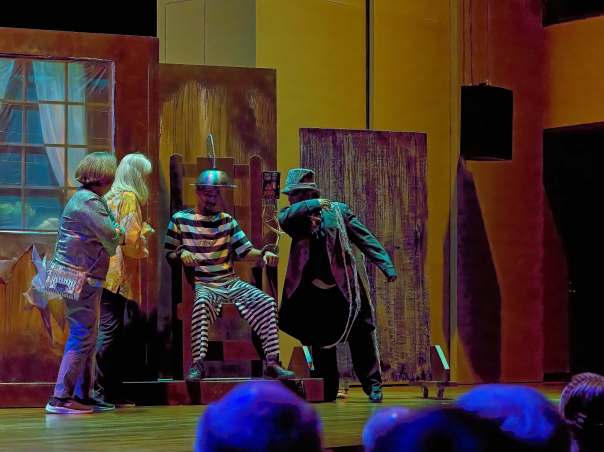

The world premiere of LaBorde’s play opened last week at Matthews Playhouse and runs through September 29 at the Fullwood Theater.

While it’s intriguing to wonder how Charles’s grandparents, Oscar and Edwina, coped with this limbo year of unofficial death – maybe holding out hopes of a miracle for a few weeks or months – it’s hardly the stuff of sustained suspense and drama. To achieve these enhancements, LaBorde applies some research, imagination, and basic math.

Time-travelling back to his grandparents’ farm in Hessmer, Louisiana, which wasn’t big enough to be incorporated until 1955, LaBorde modestly multiplies the number of local families impacted by the Rowan’s sinking. Now two moms down in Cajun country are grieving over their lost sons, Edwina and Ella Broussard, an ailing black washerwoman who takes in laundry from the richer families in the region.

Everybody seems to know everyone else around town, so when the Naval Officer shows up on Edwina’s front porch to deliver his sad news, she can point him in the right direction toward the part of town where Ella presumably lives. The fact that LaBorde has invented her makes no difference. But it’s going to take far more resourcefulness from the playwright for him to even begin exploring the racial divisions and tensions that prevailed in the little town of Hessmer when the dark days of Jim Crow hadn’t been dispelled, even after African Americans were welcomed by our military.

No, for that to happen, LaBorde had to find a compelling reason for Ella to appear at Edwina’s doorstep. Indeed, to fully engage us and win our admiration for Ella, the mission driving her to Edwina’s farmhouse had to be compelling enough for her to knock on the LaBordes’ front door. Now you have an action sufficiently outré to set a little Jim Crow town in turmoil.

What on earth could be so important for Ella to commit such an effrontery?

She has enough imagination and ambition to match her chutzpah, for she plans to pay tribute to both her son Lonnie and Edwina’s Joe – along with all the other 200 soldiers aboard the USS Rowan who perished fighting the Nazis. The tribute will be a quilt of 202 gold stars on a field of blue, with the two stars representing Lonnie and Joe conspicuously larger than the 200 others.

The project is worthy, and quilting 202 squares with 202 perfectly centered stars, along with a suitable border to frame it all, seems to be a sufficiently monumental task to occupy two women for the better part of a year – once the ladies have solved the math problem of how to symmetrically configure those 202 stars. Director Dennis Delamar certainly isn’t going to gloss over the problem of getting the math exactly right.

But that front door thing is key (even though Edwina is proud to say it’s unlocked) and obliges LaBorde’s family to be tested onstage in a manner they probably never faced in real life. To the playwright’s credit, neither of his kinfolk is perfect in receiving their surprise guest – who should, as everybody in Hessmer knows, be knocking at the back door.

That is the attitude here from both Edwina and Oscar when they first encounter this unfathomable cheek. Just to double-underline the point that the LaBordes are not perfection, Edwina rebuffs Ella twice. Yet we soon see that they are willing to evolve, uniting with Ella’s cause once they’ve heard her out. Granting her the unique privilege of entering by the front door. But what about the rest of the town? Here is where LaBorde can inject suspense, drama, and a sprinkling of terror.

Joshua Webb’s set design, with its wood-burning stove and perpetual coffee pot centerstage, has a rusticity that allows for a wisp of primal danger and violence lurking beneath its humble domesticity. Both kitchens are lovingly dressed, but sightlines are a rather dreadful problem: unless you’re seated in the center or toward the right side of the Fullwood Theater audience, you might go home never knowing that Oscar had been visible building his stone wall – hidden by the Broussard kitchen to those of us sitting on left – in defiance of stone-throwing yahoos (or KKK) repeatedly breaking the LaBordes’ windows.

Complemented by Sean Ordway’s moody lighting design, which casts a spell even before the action begins, Yvette Moten’s costume designs have the timelessness of Norman Rockwell paintings on the covers of old-timey Saturday Evening Post magazines. It’s hard to resist the visual charm of this production as Delamar frames one memorable tableau after another. From the time we first see the spirits of Young Lonnie and Joe (Aaron Scott Brown and Bennett Thurgood in rather touching non-speaking roles) to the great starry quilt reveal, Delamar lavishes a series of freeze-frames that are a memorable slideshow within the show.

Some discreet subtraction is applied to LaBorde family history that results in somewhat awkward casting for the leading ladies, Paula Baldwin and Corlis Hayes. Nowadays, we’d expect moms of strapping young military enlistees to be in their forties or fifties, not 60+ – but the real Edwina had way more offspring than two sons, so she actually was aged 60 at the time of Joe’s death.

So sitting at her kitchen table, sustaining her renown as the county’s quilting queen, and looking rather matronly, Baldwin is exactly what LaBorde envisioned as Edwina. Life on the bayou does take its toll here, so Joe will merely be the beginning of Edwina’s ennobling griefs. Baldwin endures these crucibles like so many we’ve seen from her over her distinguished QC stage career, with signature stoicism. Neither Delamar nor LaBorde had any hesitation in casting her.

As for Hayes, I first encountered her at Johnson C. Smith in 1988 when she directed for colored girls at the tender age of “24” – just guesstimating here – so she’s also perfectly cast as Ella. Maybe the most heartwarming aspect of this production is the gift LaBorde has given her with a world premiere credit in this role. Confronted by both black and white folk, Ella is a far more nuanced and varied character than we normally see Hayes portray.

We instantly see the strong spine that brings her to Edwina’s door – twice – and we see her pragmatism in backing off the first time. She seethes back home and resolves to repeat her effrontery, still knocking at the front door. Then there’s the beautiful passive aggression when Edwina belatedly agrees to allow Ella over her front threshold. Hayes pointedly hesitates, referencing the insults she has previously absorbed and the dignity she maintains.

LaBorde has obviously labored over Ella, for she has her maintaining this steely dignity when confronted by her minister, Reverend Johnson, and even when she is complimented by white churchlady Nodie Ardoin, Edwina’s nemesis. Yet there’s one more telling Easter egg to be found in LaBorde’s script, that Hayes and Delamar brilliantly emphasize. As soon as Ella gets the first clear sign from Oscar that she might not be welcome in his kitchen, we see Hayes instantly cowering, clutching her pocketbook, and readying for a quick exit.

That’s the kind of good sense Ella has, for all of her sturdy spine. We can be thankful that this rich role has finally found Hayes.

If it weren’t obvious before, One Year to Die signals that Matthews Playhouse has joined the ranks of Metrolina community theatres that consistently present pro-grade work. The standard set by Hayes and Baldwin is met by the men who portray the Hessmer clergy, Steve Price as the soulful Father Morton only slightly upstaged by the charismatic Keith Logan as Rev Johnson. LaBorde would have done better by both of these religious leaders if he had refrained from broadly hinting that Catholic and Baptist ministers follow the exact same script when upbraiding wayward lady congregants.

Aside from Oscar, the other guys we see onstage are military, so we never sample the boorishness or the toxic philosophies of the town’s window breakers. The military cameos, however, are beautifully handled by Vic Sayegh as the Naval Officer who rocks the LaBordes’ world and Brian DeDora, who appears as The Sailor after the Normandy invasion.

Possibly, LaBorde dropped the idea of including the rock-slingers onstage, for Nodie bears the same last name as one of them. Robin Conchola as Nodie is actually the more benign of the “watchin’ committee” that darkens Edwina’s doorstep to register their condemnation, a lot more conflicted than Barbara Dial Mager as Sarah Jeansonne. It’s Conchola as Nodie who has the chance to be rebuffed by Hayes. Sarah is slower to evolve, so we can despise Mager longer, if only for her horrid wig.

As Oscar, also aged 60 when Joe perished at sea, Henk Bouhuys is delightfully homespun, although there’s still enough Jim Crow ingrained in him to be shocked by the ladies’ audacity. Bouhuys continues to project ambivalence long after Oscar decides the memorial project is worth doing no matter how the rest of Hessmer may think. Once he gives Edwina his assent, his loyalty is as steadfast as his love.

Whether it was absent-mindedness or a directive from Delamar, Bouhuys only intermittently sounded Cajun on opening night – while the rest of the players hardly bothered with an accent. So it was startling when Oscar became full-out Cajun just before intermission after a cowardly attack on the LaBorde farmhouse. Out of nowhere, the accent was stunningly convincing, adding some sharp ethnic spice to the most fiery monologue of the night.

Photos by Perry Tannenbaum