Reviews: White Box, Polar Bear & Penguin, and The Turn of the Screw

By Perry Tannenbaum

Programming at Spoleto Festival USA is noticeably more fragmented and bunched-up this season (May 23-June 8), making it a little easier for jazz fans and theatergoers to see the entire sets of offerings without overstaying their budgets. Most of the jazz performances are blocked together on the tenth day through the sixteenth day of the 17-day festival, though Cecile McLorin Salvant and Phillip Golub could be savored on Days 5 and 6. Theatre presentations, however, were not to be seen at all until Day 7, and will continue – though never more than three of the five at once – until the last evening of the festival.

But the best theatre you’ll see here in Charleston this season may turn out to be an opera, Benjamin Britten’s The Turn of the Screw, with a script by Myfawnwy Piper adapted from Henry James’s ghostly novella. The world premiere production is directed by Rodula Gaitanou, who triumphed so decisively with her revival of Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti’s Vanessa two seasons ago.

The Piper script is certainly more family-friendly than the James novella – but not altogether stripped of the novella’s wispy psychological complexities. Scenes are more fragmentary than most old-time operas, more in keeping with the layout of a Renaissance tragedy. Yet Gaitanou doesn’t settle for our imagining the scene shifts from indoors to outdoors or from night to day.

Each scene change in Yannis Thavoris’s extremely supple, elegant, and creepy scenic design is punctuated at Dock Street Theatre – which itself dates back to 1736 – with the drop and rise of a black scrim. These blackouts take us back to the days of silent film, before the simplicity of jump-cuts was imprinted into our DNA. They also place a greater emphasis on the wonders of Britten’s interstitial music, which almost covers every scene change behind the curtain perfectly.

In the one exception, where the scene change must happen without musical cover, soprano Elizabeth Sutphen as James’s famously inexperienced and beleaguered Governess steps in front of the curtain for the space of an aria while the scenery changes behind her. The whole effect of Gaitanou’s staging was magnificent in a way that I hadn’t anticipated. Britten’s music seemed to infuse the pores of every actor, even boy soprano Everett Baumgarten as the possessed Miles, whose vocal lines were as simple and pure as a choir boy’s.

No wonder legendary soprano Christine Brewer as Mrs. Grose, the housekeeper, believes that Miles was incapable of violence. And indeed, the horrific denouement hinges on the boy’s natural delicacy. All is not placid when the child draws our attention. There is major orchestral turbulence when Miles, behind the Governess’s back, tears up the letter she has written to his uncle – and wild skittering sounds when he hurriedly gathers up the pieces of paper from the floor.

Not only does Thavoris’s scenery harmonize with his costume designs and synchronize with Britten’s music, it is wondrously detonated by Paul Hackenmueller’s lighting. At key moments throughout the two-act opera, the huge mirror that nearly dominates the set turns translucent or transparent, revealing the ghosts that haunt the estate. These ghosts might simply stand there in Hackenmueller’s eerie blue light or they might come to melodramatic musical life and sing.

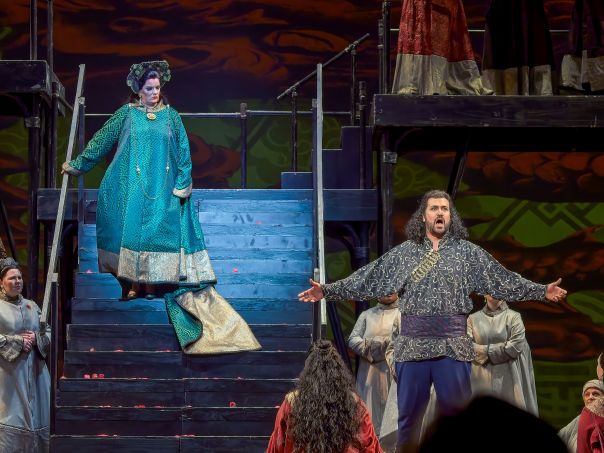

Omar Najmi sings the narrative prologue before tackling the charismatic tenor role of Peter Quint, the more malignant of the two ghosts. His wholesome and romantic appearance, like Miles’, belie the evil lurking within – but Quint’s evil is never under musical restraint. There never needs to be any question that Quint is a madman, and Najmi never leaves any doubt.

The struggle between Quint and Miles is more titanic than that between the other ghost, Miss Jessel, and Miles’ sister, Flora. Yet an extra eeriness had wafted into this Spoleto world premiere on opening night because the singer portraying Jessel, Mary Dunleavy, was still recovering from an illness. She still acted the role, lip-synching to Rachel Blaustein, who sang the role from offstage. Blaustein sometimes sounded sepulchral and indistinct from wherever she was sequestered, in and outside Dunleavy’s body, depending on where she stood.

Fortunately for Blaustein and all the other treble voices at Dock Street, but especially for us, there are English subtitles on hand when the text might otherwise be lost. Sometimes, as when Baumgarten sings “Malo, malo,” it’s just good to have the projected text above the proscenium to confirm what we’re hearing!

Aside from the oddity of these subtitles for a Broadway show, it’s hard to see why this gripping production couldn’t be a hit. Dunleavy’s interactions with Israeli soprano Maya Mor Mitrani, singing the role of Flora, are particularly outré and suggestive. Though the text never seems to give her enough to justify her take, Mitrani’s brattiness only clashes with the elegance of her lavish Victorian dress, and there’s a frequent sense of jealousy toward Miles because of the attention he draws under Quint’s spell.

In the climactic lake scene, where the ghost of Jessel supplicates Flora, Gaitanou tosses aside any notion from fussy modern lit critics that there is ambiguity on whether James’s ghosts are real or figments of the Governess’s fevered imagination. We see Jessel, floating above Flora in her boat on the lake, long before the Governess does. Until then, she’s quietly ashore on a quaint little bench, absorbed in a book.

Numerous creepy touches abound, not the least of them involving the onstage curtains that hide or highlight the ghosts lurking behind the huge mirror. Suddenly the curtain begins rustling behind the children and adults onstage – yet nobody there notices for the duration of the scene. But we do.

White people obsessed by the white polar regions has been a powerful theme since Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein (1818) and Edgar Allen Poe wrote The Narrative of A. Gordon Pym (1838). It was still in the air when Swedish adventurer Salomon August Andrée proposed a new method of mapping out the North Pole to the Royal Geographic Society in 1895: exploring the region in a hydrogen balloon.

Once again, wind conditions weren’t ideal. But Andrée, more adventurous than patient, lifted off with his comrades anyway and… vanished. For 33 years, nobody knew their fate for certain until their remains were recovered and brought back ceremoniously to Stockholm in 1930. The fullest narrative took another 66 years to recover, pieced together with the journals of the three explorers and the partial restoration of Strindberg’s photographs.

Sabine Theunissen rewinds the story in White Box in its US Premiere at Emmett Robinson Theatre on the College of Charleston campus. From a theatrical standpoint, it’s a very quirky and visual retelling, making liberal use of Nils’s photographs and primitively enhanced animations. He seems to be more of Theunissen’s protagonist than Andrée, but none of the three men onstage has any dialogue.

Thulani Clarke and Fana Tshabalala are designated as Dancers in the Spoleto program book, while Andrea Fabi is labelled Performer, presumably because he shapeshifts between Nils and Andrée. Given the silence of the humans, the old-timey camera, mounted on a wooden tripod and occasionally capable of a life of its own (thanks to puppeteer Meghan Williams), could be regarded as a fourth character.

So far what we’re describing might be viewed as akin to silent film, even though Catherine Graindorge adds violin and viola from one side of the hall and Angelo Moustapha adds piano and percussion from the other. Not even granted a bio in the program – or present for the final bows – Maria Weisby delivers all the info we can hear via pre-recorded Voice Over.

It’s hard to detect any consistent intent or message in Theunissen’s various caprices. Her Dancers are part of the expedition party and they aren’t. Their choreography from Gregory Maqona is more African than Nordic and so are their skins. The same disconnect doesn’t always apply to Graindorge’s music composition, but aside from the honky-tonk piano by Moustapha bookending the narrative, his percussion has more of a jungle flavor than an evocation of windswept Arctic tundra and ice caps.

And Theunissen’s declaration that she must tell her tale backwards to tell it right isn’t religiously carried out – though we did learn why the expedition was doomed from the start toward the end of the show. Somehow, all of Theunissen’s quirks and incongruities worked beautifully, even poetically. And viscerally.

When Nils stands doomed on a sea of ice, dancing with his mammoth camera, we can join him in tossing accuracy and logic to the winds.

Even more fanciful was the children’s show that opened on the same Saturday that White Box closed, Polar Bear and Penguin, written and acted by John Curivan and Paul Curley. Brrrrr! So theatrically speaking, it was a bipolar weekend in balmy Charleston.

Curivan and Curley (who better to concoct this alliterative title?) had some bipolar intentions of their own. For polar bears are only found natively in the northern hemisphere while penguins are natively confined to the south. Wherever they bump into each other on runaway icecaps, their personalities are also poles apart, replicating the ancient grasshopper and the ant fable. In floating igloos.

As Polar Bear, Curivan is all carpe diem: see a fish, catch a fish, eat a fish. Curley is more communal, considerate, and calculating as Penguin. In the here-and-now, Penguin will catch a fish and share a fish. Longterm, he will catch another fish and save it for later. Curivan uses his paws to bash a hole in the ice and grab his prey. The more sophisticated Curley – yes, Clara Fleming’s costume design includes full-length tux jacket and tails – extracts a fishing pole from Penguin’s little cave.

Ah, but they don’t merely catch fish out there in the frozen North or South. Penguin hooks a bottle, Polar Bear hooks a shoe, and something with buttons pops out of the deep, maybe a cell. Curivan and Curley subtly remind us with these human throwaways – and the occasional sound of airplanes above – that these primal and adorable creatures are cast adrift and endangered by the overreach of civilization.

Global warming.

Meanwhile, Polar Bear and Penguin demonstrate that their differences can be bridged as they become best friends. Until a crisis emerges at a cookout that irresistibly engaged the participation of the ankle-biters in the audience. Penguin was cooking up a glorious fish dinner from a hidden spot upstage while Polar Bear was downstage waiting for dinner, sorely tempted by an overflowing pail of raw fish that they had caught and agreed to save for later.

Each time Penguin exited to tend his unseen campfire, a new wave of temptation assailed Polar Bear. As if Peter Pan and Tinkerbell were hovering somewhere in the darkened hall, children all over the Rose Maree Myers Theatre in North Charleston began hollering to Polar Bear not to eat the damn fish.

In some ways, our innocence remains intact.

But Curivan and Curley didn’t leave us with a happily-ever-after ending. Before the lights went down, Polar Bear and Penguin reconciled, closer friends than ever before. Bear achieves better impulse control while Penguin tempers his hoarding tendencies. All that chumminess, sad to say, didn’t prevent a further thaw of the ice that connected their little caves. So they finally drifted towards opposite wings of the stage, separated forever.

A little girl sitting in front of us burst into tears, inconsolable as her mom carried her away. She likely got the point more keenly than her peers – and likely better than many of her elders here in Trump Country.

The bulk of Spoleto’s theatre lineup has yet to open, The 4th Witch opening on June 4, Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski making its bow on June 5, and Mrs. Krishnan’s Party arriving on June 6. Until then The Turn of the Screw reigns as my top pick, with a final performance on June 6.