Review: Opera Carolina’s Turandot

By Perry Tannenbaum

When we gauge the cultural influence of Giacomo Puccini, we’re most likely to invoke the operas he composed that were subsequently repurposed into megahit Broadway musicals. The American colonialism that fueled the domestic tragedy of Madama Butterfly eventually suffused the spectacular Miss Saigon, and La Bohème, Puccini’s verismo masterwork was Americanized – Greenwich Village filling in for Paris – and turned even more successfully into Rent.

But we don’t readily think of Puccini in terms of grand opera, ALL CAPS, unless we narrow our focus to the Italian master’s last work, Turandot, the one opera he didn’t live to complete or see premiered in 1926. The fate of nations routinely hung in the balance when Verdi selected his libretti, but for Puccini, this tale of ancient China and Peking stands apart from his more private and intimate norm. If Traviata is Verdi’s most visionary work, anticipating Puccini, then Turandot is Puccini’s grandest and most retro work.

Opera Carolina’s history with the work tallies well with its popularity. This is the sixth time the company has staged Turandot, decisively trailing Puccini’s big three, Bohème, Butterfly, and Tosca, two of which have reached double figures. Yet since James Meena, a devout Verdian, arrived on the scene in 2000, Turandot has maintained parity with its kindred, staged three times since the turn of the century.

We must, begging Milady’s pardon, bestow an asterisk next to the current incarnation of Peking’s princess. If she wasn’t exactly a last-minute or eleventh-hour replacement for Camille Saint-Saëns’ Samson and Delilah, it’s fair to say that she was an eleventh-month substitution for the previously slated season closer.

Yes, a grand opera was inserted at Belk Theater as the clock or calendar was winding down! Around the world, Maria Callas, Birgit Nilsson, and Joan Sutherland are among the celebrated dramatic sopranos who have graced the powerhouse title role, and the Franco Zeffirelli production at the Metropolitan Opera is as revered for its stateliness and splendor as the Notre Dame Cathedral.

Grand? Monumental.

Needless to say, the Opera Carolina production didn’t figure to deliver legendary grandeur. But instead of smoke and mirrors, set designer Anita Stewart and lighting designer Michael Baumgarten call upon scaffolding and projections to bridge the gap. Stage director Jay Lesenger wisely keeps the curtain down over Stewart’s barebones set until Meena, down in the orchestra pit with the Charlotte Symphony, can begin working his magic with the score. It doesn’t take long to taste its beauties, ranging from delicate to majestic, or realize Meena’s deep affection for it.

Parallel to the build-up to Prince Calaf’s climactic confrontation with Peking’s ice goddess, when the princess asks him three riddles that he must solve – or die – there’s a steady build-up of ritual. A Persian prince has failed the Trial of Three Riddles and must be beheaded. To declare his candidacy, against the fervent wishes of his father and his dear maidservant, Calaf – “The Unknown Prince” – must strike the gleaming gong near the gates of the imperial palace. To stage a new trial, there must be a public proclamation, holy men must gather, the Emperor must preside, and Turandot herself must pose the riddles.

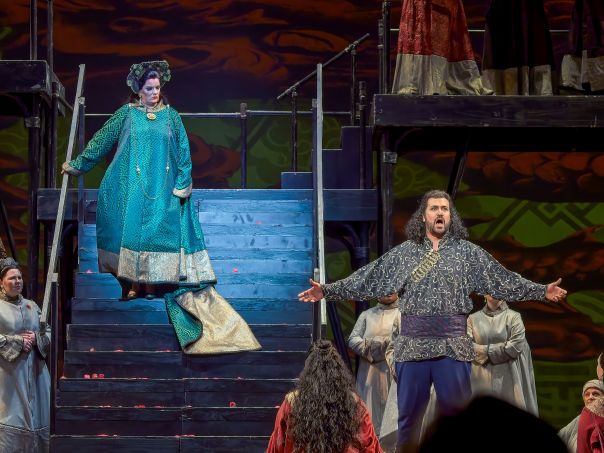

It’s a regal crescendo of pomp, ceremony, and colorful, eye-popping costuming from Anna Oliver that ultimately matches the trumpets heralding the divine Principessa. Watching the royal entrances of Emperor, Turandot, and their respective ministers and maidservants, high up and almost level with the proscenium, I had to wonder how much more scaffolding and stairs there must be hidden in the wings so that all these nobles, old and young, could safely ascend to those lofty heights.

At ground level, my worries began as soon as soprano Jennifer Forni made her auspicious Opera Carolina debut as Liù, the maidservant who has devoted herself to dethroned Tartar king Timur simply because her son, Calaf, once smiled at her before he fled the kingdom. Forni distinguished herself within the first ten minutes with her sweet fruity timbre recounting Liù’s backstory, and her buttery soft notes put the protagonists waiting for their big moments in serious jeopardy of being upstaged. After all, Renata Tebaldi, Renata Scotto, and Montserrat Caballé are among the notables who have been drawn to this role.

If we don’t see or hear the very best of Diego Di Vietro early in Act 1, there was enough Luciano Pavarotti DNA surfacing in his tenor to assure us that he would likely be equal to Calaf’s big “Nessun dorma” moment when the curtain rose on Act 3. The extra panache that was missing before intermission arrived on time, and Lesenger made more of Calaf’s first private moment with Turandot, calling upon Di Vietro to conquer the princess with brutish aggressiveness and charm. The chemistry that was so sorely missing when Opera Carolina brought Turandot to the Belk in 2009 had finally been recovered, making for a more deeply satisfying ending.

Though Lesenger could have given her more to do during Turandot’s icy phase, Amy Shoremount-Obra was certainly majestic, intimidating, and cruel as the Principessa in the stunning trial scene. Nor am I quite sure that Baumgarten took the best approach in lighting the Princess when she first appeared. Yes, Shoremount-Obra was dazzling but blinding might be equally accurate as the lights were so dazzling that there was no chance to behold the beauty of the Princess’s face, utterly bleached by the spotlight. (My photographer agrees.)

Yet there is visual drama in this tense ceremony as Turandot gradually descends the long staircase from her lofty height as her successive riddles are solved. Shoremount-Obra visibly becomes more human and vulnerable as she comes closer to the Unknown Prince’s level at the climax of Act 2 and he proves more and more worthy of her. The dramatic soprano’s stamina wavered just slightly after intermission in her pre-dawn duet with Di Vietro, but by this time, Shoremount-Obra’s beauty had been revealed and the chemistry was kindled.

Otherwise, there was no lack of strength or color among the remaining cast. John Fortson was austere and imposing in all of the Mandarin’s proclamations. Jeffrey McEvoy, Zachary Taylor, and resident artist Johnathan White were delightful as Ping, Pang, and Pong when we needed comic relief. Garbed and bearded in gray, basso James Eder brought out a paternal spirituality in the blind King Timur, and Elliott Brown, decked out in enough gold to be declared a Sun King, was a magnificent Emperor Altoum.

Rather electrifying, all around. Bravi.

Photos by Perry Tannenbaum