Review: Mojada: A Medea in Los Angeles at The Arts Factory

By Perry Tannenbaum

When Euripides took first place for the first time at the Dionysia Festival, Athens’ five-day playwrights showdown celebrating Dionysius, it was so long ago that theatre scholars aren’t sure whether he won an ivy wreath or a goat. Ten years later, when his Medea took third place, we can’t say what the Greek master took home as a reward. It wasn’t gold or bronze, but Olympic champions and runners-up back then didn’t win medals, either. Nor can anyone remember the titles of the tragedies that finished ahead of Euripides’ masterwork.

Now that Luis Alfaro’s Mojada: A Medea in Los Angeles has premiered in an excellent Three Bone Theatre production at the Arts Factory, we can say – 2455 years and five months later – that we are a giant step closer to seeing a premiere of Euripides’ white-hot spectacle in Charlotte. Until now, the closest approach of the charismatic adventurer Jason and his sorceress consort Medea to the Queen City was a 2004 Gardner-Webb U production in Boiling Springs.

That production, one might presume, came in the wake of the sensational 2003 Broadway revival of Medea starring Fiona Shaw. But was there also a connection between that Media and Alfaro’s?

Could be! For the Broadway sizzler also transported Euripides’ hellcat to Los Angeles. But there’s also a huge difference: Shaw’s Medea was a Hollywood superstar who capriciously craved a Garbo-like solitude. Alfaro’s is a mojada, or wetback, who needs to lay low because she’s an illegal – and mostly because, during their treacherous migration from Mexico, she suffered far more severe trauma than the rest of her family and their longtime viejita, Tita, who is always seething over the indignity of being considered a “housekeeper” in America.

She considers herself a curandera, a healer, so she tracks with the Nurse in Euripides’ tragedy. After winning the 1948 Tony Award for Medea – and recreating the role for a 1959 TV movie – Judith Anderson was content in 1982 to take on the role of the Nurse in another Broadway revival, earning a second Tony Award nomination with the same Robinson Jeffers adaptation.

So you can expect Banu Valladares as Tita, Christian Serna as Hason, and Sonia Rosales McLoed as Medea all to have potent roles to play in Alfaro’s explosive retelling. Unlike Euripides, Alfaro flashes back to the treacherous journey that brought Hason and Medea to the Rio Grande, with enough hardships, suffering, and trauma to suggest a parallel to the Middle Passage from Africa. And of course, Medea’s barrio lifestyle also tracks with Langston Hughes’ “dream deferred” in Harlem – both of them pulsating toward an explosion.

Alfaro shakes up Euripides’ cast as well, replacing both kings, Creon and Aegeus – and the unnamed, offstage daughter Creon expects Jason to marry – with the sassy, bossy Armida, Hason’s employer and benefactor. We might also say that Alfaro has replaced the Euripides’ Chorus of Corinthian Women with Josefina, a bread-peddling gossip making her daily rounds.

Confronted with a rich mixture of Spanish and English, spoken with authentic Hispanic accents by an all-Latine cast, we may feel as disoriented in this Chicano world as Hason’s family are in LA. Seeing a quiet Medea, burdened by an oppressive workload and timidly tethering herself to her sewing machine, we further struggle to connect Alfaro’s protagonist with Euripides’. Back in Corinth, the royal Medea was outraged, suicidal, and wildly vengeful from the moment she first appeared, a volatile dynamo of shifting, fiery emotions.

Since we come into Alfaro’s story a little earlier, it will take a little while for his tragedy to overlap the Greek’s, even if you read it the night before. And if, like me, it’s been over 20 years since you’ve seen the work live or read a translation, you may miss some of what Alfaro has preserved from Euripides’ telling. For Euripides, it wasn’t such a big deal that Jason and Medea were immigrants, but they were. For me, I hardly noticed that Jason and Medea weren’t legally married, but they weren’t.

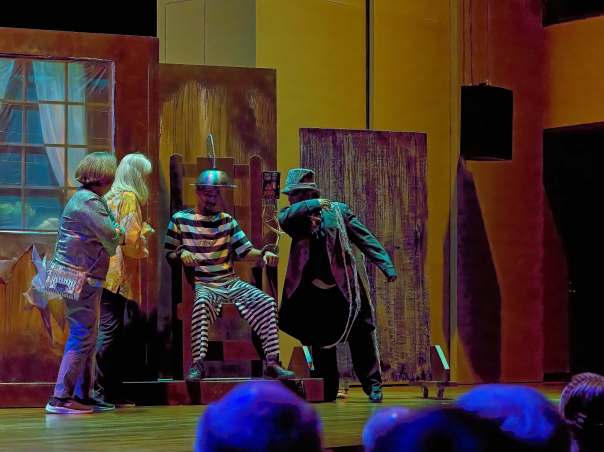

For Alfaro, these are central plot points. Just don’t think he’s changing those parts of the story. It’s really brilliant how they’re elevated to top-of-mind when we watch Mojada at the Arts Factory. Complementing their all-Latine cast, most of whom are making their first appearances with Three Bone, are directors Carlosalexis Cruz and Michelle Medina Villalon, also in their Three Bone debuts. They don’t always listen to their players with helpful Yankee or Dixie ears, but they deftly quicken the heartbeat of this drama as it climaxes.

More importantly, when they reach the spectacular ending, what they concoct – with Jennifer Obando Carter’s most unforgettable costume design – hits the spot. We could feel that viscerally on opening night.

Obviously, Latine theatre wants to happen in the Queen City. With Three Bone committed to producing Alfaro’s complete Greek Trilogy, Electricidad next August and Oedipus El Rey slated for 2026, it’shappening.

Because Alfaro is messing with both the story and Euripides’ character, those who know the Medea myth can experience the suspense at nearly the same high intensity as audience members who have never come across this Mom-of-the-century before, in Greece or in this LA rewrite. Over and over, as memories of the Euripides’ came flooding on me from past encounters with the live Shaw, the TV Anderson, and the text, I found myself wondering, Is he really going all the way?

After all, part of the reason Euripides’ Medea hasn’t played in Charlotte for at least the 37 years that I’ve been on the beat could be that Queen City theatre companies were protecting us from its full barbaric force. Could be some blowback in Bank Town.

Thanks in large measure to the harrowing flashback sequence, McLoed is able to traverse the wide gulf between the semi-catatonic Medea we confronted at the beginning of the evening and the flaming red raptor we see at the end. That’s Medea!? I found myself wondering during Scene 1, so the development arc from there is nothing less than astonishing. There’s a haunting connection between the catatonia we see at the beginning and the vengeful glare that comes some 90 minutes later. She’s actually relatable most of the time!

Precisely because this LA Medea lacks the fire and wicked glamour of her Corinthian counterpart in the early scenes, we can effortlessly empathize with Serna’s ambitious Hason as he pursues the American Dream. She won’t leave the house! Family outings with their son cannot happen, she’s too traumatized for sex even when she’s in the mood, and. He wants to get ahead while his Medea is a poster girl for inertia.

And considering the huge difference between an immigrant’s status in modern-day America and his relative safety in ancient Corinth, Hason has many pragmatic reasons to accept the predatory Armida’s business and marriage proposals, no matter how much he may still love Medea. Giving us earlier access to the story – before the breakup – not only allows Alfaro to add fuel to the drama, it allows him to show us that there is fault on both sides.

Serna’s performance isn’t quite as wide-ranging as McLoed’s, but it is no less nuanced, for he is navigating this new American world and trying to provide for his family’s future. We see that he’s a far better parent to his son, Acan, than Medea, and it’s not just because he kicks a soccer ball around with him in the front yard. Citizenship for him, no matter how heartlessly he betrays Medea, will mean citizenship for the boy.

In her venomous cameo, delivered with a wondrous mix of elegance and malignity, Marianna Corrales is magnificently resistible as Armida, Hasan’s childless employer and Medea’s implacable landlord. Hard to say whether Armida wants Acan as a son more than she wants Hasan as a husband, but with knowledge of Medea’s immigrant and marital status, she knows she is invincible and will have her way. Corrales is cool. Ice.

Alfaro not only gives Leo Torres more to say and do in his story as Acan than any of Jason’s children have ever had before, he makes him a key part of the tale. Torres will not only tell his mom about visiting Armida’s swank house with Dad, he will also – huge new dramatic irony – suggest that she make the rich lady a dress.

Further igniting Medea’s suspicions and jealousy is Isabella Gonzalez as Josefina, bringing her signature vitality along with her cartful of bread as she shares gossip with Tita. Yet she is also eager to make friends with Medea, especially if a certain amount of freebie loaves will convince the artful seamstress to make her a smashing new outfit. So it makes sense, out of friendship, that she tells Medea what the buzz is around town about Hason and Armida.

We never learn how long Hason has actually been married – or how far custody proceedings have gone – when Medea gets the newsflash. This point in Alfaro’s LA comes late in the drama, but in Corinth all this has happened before we first see the sorceress. No wonder the rest of the evening was such a feverish whirl.

In hindsight, after dipping back into the original 431 B.C. playscript, methinks it was far crueller that Alfaro’s Medea sends Tita – instead of Jason and the child – to deliver her bridal gift. Cruel as it is to make the viejita a witness, it gives Valladares a monologue that even Judith Anderson would have loved to sink her teeth into. As the eternally griping Tita, Valladares seems to hate everybody, beginning with us, whom she addresses directly after Alfaro’s incantatory opening.

But she has crossed rivers, faced outlaws and starvation, because of her loyalty to Medea, the one person she adores. And now Medea sends her off with a giftbox to Armida and tells her that she herself is a second gift for Hason’s benefactor. Discarded like an old rag!

Plenty of steam to work with. Valladares does not misfire. Nor does McLoed, though we hear an ominous helicopter overhead.