Living Legends and Young Lionesses Featured in Spoleto Festival USA Jazz Lineup

Preview: International Lyric Academy Summer Festival

By Perry Tannenbaum

Look up, look around, and look quick. There’s a new international music festival here in Charlotte, and it’s already in progress. Opera Carolina announced their new International Lyric Academy Summer Music Festival mid-week a week ago, two days after the 86 singers who will performing arrived in the Queen City to begin master classes and rehearsals. The first Festival event, a Florilegium concert, was staged on Wednesday night at Central Piedmont Community College.

Apparently, Charlotte was not caught by surprise. Both the Wednesday and Friday night performances of Florilegium were moved from the upstairs Tate Recital Hall in the Overcash Building to the larger Dale F. Halton Theater below, where the popular CP Summer Theatre resided in the good old days.

Founded in Rome and now based in Vicenza, Italy, the International Lyric Academy has staged 28 Summer Festivals since 1995, but the 2023 will be the program’s first festival in the US. So yeah, this is quite a coup for Opera Carolina and artistic director James Meena.

Singers in the opera program will perform two additional concert programs, a Mozart Marathon (June 29) and an Opera Scenes Program (July 3) before two operas take over the Halton stage for two performances each, a semi-staged Tales of Hoffman (July 5 and 8) and a fully-staged Marriage of Figaro (July 6-7). Meanwhile, 30 more singers are flying into Charlotte for the Broadway musical component of the ILA Summer Festival.

Before ILA’s first US festival concludes next Saturday with the evening performance of Tales of Hoffman, the musical theatre singers will sparkle on the Halton stage with a matinee tribute to Richard Rodgers, With a Song in My Heart. For the opera singers, the show will go on – to Vicenza, where they will reprise their US opera and concert performances.

“The whole company gets on a plane and we go to Italy for two weeks and do classes with different master teachers there and perform in the theater,” says Meena, who is ILA’s guest conductor in Italy. “Vicenza is between Venice and Verona. So basically, we take over the theater for two weeks. These emerging artists get to perform here, and then they actually get to perform in Italy. We’ve invited a handful of intendants [opera impresarios] from Italian theaters to come to the performances and hear the kids. So it’s an amazing opportunity for them.”

The new festival in Charlotte represents a quantum leap in Opera Carolina’s youth education program and a magnificent expansion of their resident company. Now that the pilot program has emerged from under the radar, Meena will be meeting with his board to decide whether they will authorize a complete integration of the Academy into Opera Carolina – or whether they will continue working as separate entities to produce future Summer Festivals.

Working with so many emerging artists at the same time clearly had Meena excited when we spoke. While he was in rehearsals getting ready to conduct next week’s performances of Jacques Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffman, Stefano Vignati, ILA’s artistic director and founder, was readying the full-dress version of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, a comedy masterwork that figures prominently in any serious discussion of the greatest operas ever written.

The breadth of the program is as breathtaking as its sudden arrival.

“Our education department all of a sudden becomes youth through young adults!” Meena exults. “So it’s really pretty audacious. No other company that I know of other than Chicago Lyric and the Met and San Francisco are providing professional opportunities like this for emerging artists. So it’s pretty cool. We’re pretty excited about it all.”

Advertisements to attract young artists to the program began last July, and the program already has a network of university instructors spreading the word – in Toronto, Cape Town, Seoul, LA, and other US locations. The audition process began virtually before the decisive live auditions in six different cities.

When you add up the 86 opera aspirants with the 30 musical theatre recruits, you have a youth program that begins to rival that of Spoleto Festival USA, the annual arts behemoth that takes over Charleston for 17 days. Meena doesn’t shy away from the comparison.

“If we do this well,” he says, “this can become different than Spoleto but on that scale.”

There’s certainly a niche for it, since Spoleto has never done Sweeney Todd or West Side Story – and CP Summer Theatre staged both of those Broadway classics in its long history before making a quiet exit last year. But the combination of opera and musical theatre, in programming or in pedagogy is nothing new.

“We’ve been blurring the lines between American music theater and opera for decades, really,” Meena explains, “since Beverly Sills first started the City Opera, when she did Brigadoon. So it makes sense for us to get music theater kids, teach them a bit about classical singing, which can only help their performing, and then work that curriculum, really, to add some more diversity to the performances. If we do this well, by 2024, the music theater program will be probably two weeks. The opera program would be four weeks.”

Not only a big deal but a great deal. Two of the ILA Summer Festival concerts are free, and ticket prices top out at $35 for the rest. Festival passports are also on sale.

Review: Six The Musical at Blumenthal Performing Arts

By Perry Tannenbaum

Many of the people who know nothing more about King Henry VIII of England than the number of wives he married erroneously assume that he executed them all. Not so. Only twice did he behead a wife – no more often than he divorced or, more accurately, annulled one of their marriages – so four of the dears died of natural causes. Still a half dozen is a large portion of partners and death-do-us-part oaths for any grown man, especially one who lives out his life very much in the public eye.

You don’t earn a pass, even as a king, for summarily ordering your wife to be beheaded just because you refrained on other occasions. Nor is it a moral lapse if, three wives and six years later, you do it again after thinking it over.

What’s important, then, is the solidarity of these wives as Toby Marlow & Lucy Moss bring them all back to us in SIX THE MUSICAL. No matter that the ladies’ villainous tormentor has been dead for 476 years – and barred from appearing this week at Belk Theater as the touring version, adorned with Tony Awards for best costume design and musical score, spends a holiday week in the Queen City. These resurrected queens are out for revenge.

Queen-spired by Beyoncé and Shakira, Lily Allen and Avril Lavigne, Adele and Sia, Nicki Minaj and Rihanna, Ariana Grande and Britney Spears, plus Alicia Keys and Emeli Sandé, they are here to SLAY!! Glittering in eye-popping skirts, dresses, and slacks worthy of hardcore heavy-metal thrashers. Dazzling tops, bustiers, shoulder plates, ruffles, collars, and sparkling sleeves ready for the battlefield Wicked platform shoes and boots. State-of-the-art hand mics.

Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Anna of Cleves, Katherine Howard, and Catherine Parr are not here to play – not even with each other. They are here to ask us to decide, night after night, which of them suffered most under cruel King Henry’s hand. This is their battle, their consecrated competition.

If you are capable of biting your nails over the outcome of this high-stakes, high-decibel throwdown, then you’re likely to believe that I’m fully acquainted with all the inspirational pop queens I’ve just catalogued. Throngs of fanatics were no doubt pre-sold on Marlow &Moss’s handiwork before opening night at the Blumenthal Performing Arts Center, for their high-decibel responses often increased my difficulties in discerning what these dead queens were telling us.

A good portion of the screamers and shriekers had no doubt primed themselves by listening repeatedly to the cast album before the show or – like I did afterwards – by counting on Spotify and Apple to post the lyrics as it played. My recommendation would be to follow their example, though the sound crew’s performance on opening night was far better than average.

Intelligibility aside, as well as pertinence to the issue at hand, each of the six solos the queens sing has an unmistakable élan, and all six of the women onstage are powerhouses when the spotlight is most piercingly upon them. Of course, a Charlotte crowd is going to favor its own, and Amina Faye’s return to the Belk Theater stage as Jane Seymour, seven years after she took home a Blumey Award there for her stirring portrayal of Sarah in Ragtime – and a subsequent Jimmy Award up on Broadway – is already a triumph.

Clarity and intense emotion are already baked into “Heart of Stone,” so Faye is doubly set up for success with the Belk audiences. It’s the only song besides “I Don’t Need Your Love,” sung with searing urgency by Sydney Parra as Catherine Parr, that rises to the level of heartfelt testimony, a strange commonality for the two queens who have the least reason to feel aggrieved by Henry. Buoyed by this handicap, they are welcome counterweights to the prevailing glitz and silliness, and Faye is better to my ears than her cast album counterpart, Natalie Paris, who is comparatively plastic. Or pop plastic, if you don’t warm to that brand of singing.

Gerianne Pérez is surprisingly saucy as the senior – and longest reigning – among the royals, Catherine of Aragon, singing “No Way” in retelling how she rejected divorce and annulment from Henry. Nor does she fade into the background after taking the first solo, indisputably the most confrontational and contentious in the group. Her primary adversary, Zan Berube as Anne Boleyn, is by turns weird, wacky, lewd, and irreverent in “Don’t Lose Ur Head,” confiding that she lost her head only after giving some. Could be me, but it seemed like she was bragging, not gagging.

By the time we reached Terica Marie as Anna of Cleves and Aline Mayagoitia as Katherine, the idea that these badass queens were trying to point up their marital sufferings – or anything else besides telling their stories with varying degrees of attitude – was pretty much forgotten. Paradoxically, that made it easier to enjoy Marie’s “Get Down” as she went from down-low grooving to childish taunting. Anna seemed to be adopting Aragon’s playbook. Despising Mayagoitia’s all-men-are-alike messaging in “All You Wanna Do” came just as naturally as she narrated her way, chorus by chorus, to the hatchet man.

Interesting that the two women whom Henry beheaded get the most annoying songs. It’s a nice little hint from Marlow & Moss that the man was provoked. But then, so was the woman I heard complaining that, for 100 bucks a ticket, we should be able to understand the lyrics that these dead-queens-resurrected-as-rockstars are singing. Personally, I discarded such naïve notions at the last Avett Brothers concert I attended. At least at SIX, you can remain seated for the whole 80 minutes.

Review: Spoleto Festival USA

By Perry Tannenbaum

It’s been a tumultuous year for Mena Mark Hanna in his second season as the new general manager at Spoleto Festival USA. Chamber music director Geoff Nuttall, the festival’s most recognizable personality – the charismatic violinist who convinced Hanna to come aboard at Spoleto – died in mid-October at the age of 56 while undergoing treatment for pancreatic cancer.

Amid all his antics and flamboyance, Nuttall never seemed to be that old.

Then as all the pieces of Spoleto 2023 fell into place, including the memorial concert for Nuttall scheduled on the opening holiday weekend, last year’s centerpiece, the world premiere of Omar, won the Pulitzer Prize for composers Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels. That opera, rooted in the festival’s Charleston home, would stand as the signature achievement of Nigel Redden, Hanna’s predecessor. Redden handed over final alterations and trimmings to the new GM, who piloted the grand project into port.

So this year’s festival will likely be remembered as Hanna’s first true lineup, though Scottish Ballet, mandolin sensation Chris Thile, and iconic jazz artist Abdullah Ibrahim will be the last holdovers to file into Spoleto from the 2020 event that never happened. Yet without a replacement for Nuttall, a key member of Hanna’s hiring committee as well as an engaging host and performer, there’s a feeling that the festival remains in flux.

Even as I spoke to Hanna, a week before this year’s Spoleto began, he wavered between declaring he was in no hurry to replace Nuttall and assuring me that considering his successor was definitely on his to-do list during the festival and in the summer ahead.

It’s safer to say that sustaining the momentum for opera is an urgent priority for Hanna. Programming Samuel Barber’s Vanessa in 2023 is certainly a major statement, since its strong libretto was written by Spoleto founder Gian Carlo Menotti, and for 2024, the festival is commissioning a new opera. Announced at the same time the curtain was rising for the final performance of Vanessa, the new piece, Ruinous Gods by composer Layale Chaker and librettist Lisa Schlesinger is ballyhooed as “another bold project with powerful themes” in the mold of Omar. Opera Wuppertal and Nederlandse Reisopera will be co-commissioners and co-producers of the new chamber opera.

Menotti hasn’t been regularly involved at Spoleto since 1993, when he stage-directed one of his weakest works, The Singing Child. True, there was a revival of Menotti’s most heralded opera, The Medium, in 2011, but that production has come to seem like an obligatory celebration of the composer’s 100th birthday. Twelve years later, Vanessa feels like a whole-hearted embrace: bolder and more contemporary with Rodula Gaitanou’s daring stage direction, more searching with Timothy Myers wielding the baton.

A long pandemic after Gaitanou’s vision of Vanessa was first presented in 2016, the loneliness and isolation of Vanessa resonated more keenly in its US premiere, the effect only enhanced because her icy-cold vigil is self-imposed. The entire household seems to be in suspended animation, The Old Baroness mother perpetually painting at her easel, daughter Vanessa faithfully awaiting her former lover’s return after 20 years, and Vanessa’s niece Erika as much on auto-pilot as the maids and butlers.

All the many paintings and mirrors on the walls are covered, adding to the surreal atmosphere. It’s as if Vanessa were protecting herself from a raging plague, or as if this were a summer home about to be abandoned until next year. The futile circularity of the Baroness painting pictures that will be covered up as soon as they are hung up on the wall subtly prefigures what will happen when Vanessa’s beloved Anton arrives.

As Hanna had promised, the cast was killer. Nicole Heaston brought a neurotic hauteur to Vanessa, a steely cold soprano in her rendering of the tense “Do Not Utter a Word” aria that weirdly echoed Rosalind Plowright’s iciness as the Baroness, a role that the English mezzo originated at the Wexford Festival premiere of this production – before she reprised the role at Glyndebourne in 2018 (available on DVD and Blu-Ray). Compared to the stony and unwavering Plowright, Heaston’s Vanessa proved to be vulnerable, capricious, malleable, and oblivious in a quietly disturbing way.

If Heaston personified the creepiness and the supernatural tinge of Menotti operas, mezzo Zoie Reams as Erika inclined more to Barber’s sad and wistful Romanticism. More emotion poured out of her in “Must the Winter Come So Soon” than on any of the full-length recordings this side of the original live recording conducted by Dmitri Mitropoulos in 1958. Heaston ably gets across to us that her attraction to the second-generation Anton is a rekindling of her youthful ardor, but Reams shows us that Erika’s love for Anton is a first flowering, with a more hormonal heat and fire.

Yet Erika never wears her heart on her sleeve. Perhaps because of her more precarious finances, there’s a secretive and withdrawn aspect to Reams’ performance that marks her as a member of the family. So self-denying and self-destructive are they all that it becomes richly ambiguous whether tenor Edward Graves as young Anton is a ruthless fortune hunter or an idealistic romantic. It was rather wonderful, when Graves engaged Heaston in the slowly cresting “Love Has a Bitter Core” duet, how Anton and Vanessa could be seen triggering spontaneous passion in each other.

The denouement was a walloping “To Leave, To Break, To Find, To Keep” quintet with baritone Malcolm MacKenzie, a welcome presence as The Old Doctor, completing the fugal fabric. It all sounded so present and powerful at Gaillard Center, the singing perfectly balanced with Myers’ ardent work in the pit, while ever-present, precisely synced supertitles projected above facilitated transmission of Menotti’s text.

For those of us who were fortunate to attend Vanessa and the big orchestral performances of Spoleto 2023 – John Kennedy conducting The Rite of Spring, Mei-Ann Chen navigating the New World Symphony, and Jonathon Heyward reveling in the Symphonie Fantastique – the Gaillard and its fine acoustics were arguably the center of the festival. Both the Spoleto Festival Orchestra and the Spoleto Chorus, recruited in nationwide auditions, are rather awesome. And fortunate: not only do they get to perform at the Gaillard, they individually and collectively get to perform edgy, outré, and contemporary pieces at other Spoleto venues that you’re unlikely to experience anywhere else.

Chen, the music director at Chicago Sinfonietta, dug into her wide-ranging repertoire to greet us with Florence B. Price’s Ethiopia’s Shadow in America, a three-movement work that likely begins a mile or two away with an Introduction and Allegretto depicting the arrival of slaves in America. The brief yet solemn middle movement vividly evoked the famous New World Largo we would hear later in the evening, and the concluding Allegro, “His Adaptation,” had the urbane Ellingtonian strut of the Jazz Age.

Delights and Dances, gleaned from Chen’s 2013 Cedille CD that gathered three different concertos for string quartet and the Sinfonietta, was a welcome dive into an earlier Abels work in the wake of his Pulitzer. Nor was it difficult for me to exit the Gaillard feeling that the New World was Antonín Dvořák’s fantastic symphony, for the onset of the trombones in the final movement brought on goosebumps.

The lesser-known Heyward, the music director designate at the Baltimore Symphony, was not to be upstaged – not by Chen, at any rate. A native of Charleston, Heyward received a hearty greeting from the hometown crowd that puzzled the out-of-towners sitting behind me. Heyward began his grand homecoming with the US premiere of Nymphéa, a 2019 work by Doina Rotaru inspired by Borin Vian’snovel, L’écume des jours, with a sprinkling of Duke Ellington’s “Chloe,” the namesake of Vian’s heroine.

What the music evokes, partly through a delicate combo of piano and muted trumpet that grows fearsome and awesome – embroidered by plentiful percussion – is the growth of a huge destructive water lily (nymphéa) inside Chloé. Call it a 19th-century tone poem written with a 21st-century quirkiness, with a rubbed oriental gong, a plucked Steinway, and a stray mallet head that accidentally bounced into the front row of the audience.

Yet all of this spookiness was upstaged in an instant by the return of another local musician, pianist Micah McLaurin. With a glittery, androgynous, and otherworldly David Bowie aura, the slender McLaurin strutted onstage to a huge ovation in a blinding fuchsia jumpsuit with a lowcut back and a single silver sleeve. He proceeded to pound out the opening chords of Grieg’s Piano Concerto once the startled crowd had quieted, working the pedals with platform shoes, which had only increased his considerable height and the éclat of his entrance.

The outer Allegro movements showed off McLaurin’s strengths better than middle Adagio. Even there, the soft and loud passages were gorgeously shaped until late in the movement when his tone grew too steely for maximum effect. But the latter stages of the final movement were irresistible, crackling with authentic thunder.

When he reached Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie, Heyward benefited from the luck of the draw in delivering a more consistently satisfying account than we had of the New World. All 100 members of the Festival Orchestra don’t appear together, and the principals who performed featured solos with Heyward outperformed Chen’s chosen.

Not only did Heyward send his principal oboist offstage in the wondrous countryside movement, he deployed tubular bells to the wings for the closing “Witches’ Sabbath” movement to chilling effect. The drumbeats and sforzandos in that movement and in the preceding “March to the Scaffold” were nothing short of electrifying. Audience buzz after the Fantastique was every bit as enthusiastic as it had been at intermission in the wake of McLaurin’s exit.

The other Spoleto venues were rich in talent and adventurous spirit. At Dock Street Theatre, countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo performed an outrageous hybrid lark, Only an Octave Apart, with cabaret icon Justin Vivian Bond, nary a male outfit in their wardrobes. Otherwise, we could compile an epic review of the 11 lunchtime chamber music programs that rocked the Dock, though my wife Sue and I only witnessed seven – enough for us to see 11 different hosts standing in for Nuttall introducing 25 pieces (nine by living composers), including an original score by pianist Stephen Prutsman for 7 Chances, the most hilarious Buster Keaton film we’ve ever seen.

St. Matthews Lutheran Church and Sottile Theatre were both graced with concerts led by director of choral activities director Joe Miller. Surprisingly, the Festival Chorus program at the church, Density 40:1, was more secular than the one two blocks south, a precedent-breaking concept from beginning to end. Miller and his 32+8 voices all ascended to the organ loft in order to spread out over us and perform the 40 parts of Thomas Tallis’s Spem in alium. More earth-shattering, the choir did not perform “Danny Boy” or an encore. Instead, we all sang “Over the Rainbow” together.

A new venue, the Queen Street Playhouse, was added to the Spoleto portfolio with mixed success. Artistically, A Poet’s Love was a resounding triumph for tenor Jamez McCorkle, powerfully following up his exploits of last season in the title role of Omar by singing Robert Schumann’s Dichterliebe – while accompanying the entire song cycle by himself at the piano. Designer and choreographer Miwa Matreyek made this a completely immersive experience with animated projections, shadow puppetry, and the movement she designed for Jah’Mar Coakley.

But the staging was badly bungled. Once McCorkle sat himself behind the Steinway, I never saw more of him than his scalp from my second-row seat. Fortunately, Matreyek and Coakley combined on a magnificent performance I didn’t miss.

After a rather bizarre foray at Festival Hall (formerly Memminger Auditorium) for his first Music in Time concert, Kennedy made better use of Queen Street Playhouse for Sanctum, a wild collection of contemporary pieces, concluding with the 2020 work by Courtney Bryan that gave the program its title.

That piece was decisively upstaged by Everything Else, a 2016 composition that I will likely never forget. For this novelty, 15 members of the Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra laid aside their instruments and drove the everyday concept of music to new frontiers most of us had never pondered before. One musician sat with a newspaper, turning the pages at leisurely intervals, another put on a jacket and zipped it up, three of the women passed around and munched a bag of chips, and another tapped obsessively on the keyboard of a laptop while, across the stage, another blew bubbles.

All of this low-volume action – and a multitude of louder acts – continued simultaneously. There were pennywhistles, a kazoo, somebody blowing on the rim of a bottle, two guys slapping cards down on a table in a game of war, and balloons blown up, shaped, and worn as comical crowns. Of course, there was the obligatory popping of balloons near a woman who insouciantly demonstrated how many different things can be done with a bottle of water without hardly making a sound.

Kennedy had seated himself with us in the audience so he could join us. Yet every musician onstage seemed to know exactly what to do onstage, when exactly it was time to launch into a new action, and when exactly to initiate interactions with other musicians. Anyone who thought about it had to wonder how such a multifarious sea of chaos could be taught, rehearsed, and performed – so precisely that the entire ensemble, without a conductor in front of them, stopped at the same instant.

I still can’t decide whether or not I wish to know.

Review: I and You at Theatre Charlotte

By Perry Tannenbaum

Stevie Wonder made the point so memorably over 50 years ago when he dropped his Talking Book album: “You and I” sounds so much more melodious and natural than if you reverse those pronouns. As Laura Gunderson’s unique 2014 dramedy reminds us, now wrapping up Theatre Charlotte’s 95th season, I AND YOU sounds and feels rather awkward – even if it’s grammatically correct.

Predictably, the play is written for two high-school-aged people going through an awkward meeting, and director Rasheeda Moore makes the two-hander a little more fit for community theatre programming by rotating two different casts during the production’s two-weekend run. Pronouns figure prominently in the plot from the beginning, for when Anthony enters Caroline’s bedroom and meets her – without prior notice – for the first time, he’s carrying a really lame handmade poster and a fairly shabby old book, overflowing with scraps of sticky notes and bookmarks.

He’s a young man on an urgent mission, so desperate in his pleading that he almost sounds commanding. You and I, he is telling her, need to collaborate on a project for our American Lit class where we show how the meaning of I and You keeps changing during the course of Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself.” That’s a rather big ask of Caroline, a rather ornery young woman suffering from a liver disease that keeps her out of school most of the time. She actually hates poetry, let alone Walt Whitman.

Caroline’s objections to poetry and how it’s taught in school are rather intelligent, and Anthony’s advocacy of Whitman is passionate and rather erudite for a teen. If they can get together, the outcome could be provocative. We know that Caroline isn’t really going to throw Anthony out, and we know that Anthony isn’t going to storm off, never to be seen again, so it’s gratifying that Gunderson only briefly feints in those directions. Once these formalities are dispensed with, our main interest jibes with that of the people before us onstage: getting acquainted and finding out why they’re worth our time.

Gunderson keeps it personal and unpredictable, with mercifully few ensuing chances that Anthony and Caroline will break apart before they get to know each other. They do get to know each other over two acts, with multiple scenes before and after intermission. Through various disagreements, crises, musical jams, and accords – and of course, through the lyricism and the merging, pantheistic spirit of Whitman.

Along the way, Anthony’s classroom assignment becomes a subtle template. For while he and Caroline are wrestling with the multitudes that Whitman packs into his pronouns, we find ourselves on the lookout for how the I and You speaking to each other onstage are changing before our eyes – in their views of themselves, each other, and what they can do and be together. Even so, the outcome was beyond my wildest imagination, though Gunderson had skillfully dropped a hint or two.

Moore is similarly thoughtful in how she handles her two casts, the Walt Cast and the Whitman Cast. They are listed in that order on our playbills, but it was the Whitman Cast, Njoki Tiagha and John Emilio Felipe, who actually premiered this production last Friday at the Queens Road barn. That’s the cast I saw at the Sunday matinee, so the Walt Cast (Dorian Herring and Isabella Frommelt) will be performing more times during the second week of the run as they continue to alternate, evening the score for the last time at this coming Sunday’s matinee.

You’ll also notice – and perhaps appreciate – that the players in each cast are listed in the order of Whitman pronouns they will explore. Chris Timmons’ set design is richly hued, a nicely coordinated mix of turquoise, blue, and purple, always in tune with Timmons’ lighting. The décor is more dreamy than girly, particularly when Caroline turns on the little light show she has installed. Bedridden though she often is, she is outfitted with a laptop, a cellphone that serves as a gateway to her someday becoming a photographer, a smoke detector with a dead battery, and a turtle pillow that she hugs fiercely and talks to.

Anthony, we learn, is a varsity basketball player fresh from a game where he had a traumatic experience. Not a total loser with women, he comes bearing waffle fries.

Although Gunderson specifies the race of each character, Moore demonstrates that she finds such prescriptions disposable. Her results with the Whitman Cast are quite admirable, though she needs to tell both players to turn up the volume if they’re to conquer the acoustic problems of the renovated Old Barn. Even the most veteran actors who have appeared there since the grand reopening have sometimes struggled to be heard.

Tiagha is near-perfect as Caroline, particularly in mixing the teen’s intelligence with her eccentricities. She only needs to let us know a wee bit more clearly that Anthony is getting over on her and that she is falling for him (and Walt’s poetry). The opposite problem afflicts Felipe, who is perennially a couple of notches too shy and worshipful toward Caroline – he’s a popular jock at school! – without gaining sufficient confidence as he begins to make headway. While I question those choices, I must applaud how intensely Felipe inhabits every moment. Furthermore, the rapport that Tiagha and Felipe have sown is superb at every turn.

Gunderson strikes the right chord in developing her protagonists through the music they love. For a boomer like me – who owns Jerry Lee Lewis’s complete Sun Sessions as well as John Coltrane’s complete Atlantic, Impulse, and Prestige recordings – her choices couldn’t be more perfect. Or authentic. YMMV, y’all.

Review: The Book of Life at Spoleto Festival USA

By Perry Tannenbaum

Staggering our ability to comprehend, with a death toll of a million people over the space of just 100 days, the Rwandan genocide of 1994 isn’t the easiest subject to deal with, either for those who lost loved ones in the slaughter or for the international community that looked away. Co-creators Gakire Katese Odile, who speaks to us, and Ross Manson, who also directs, both know that the carnage cannot be minimized or undone.

Collaborating on The Book of Life, which premiered at the Edinburgh International Festival last September, Odile and Ross don’t even point fingers at those who sowed the deadly discord with toxic misinformation. Instead, their mission is one of healing for the survivors of the catastrophe and building concrete new hopes to replace the ruins. Staged at Festival Hall (formerly Memminger Auditorium) in its US premiere, The Book of Life is undoubtedly one of the most extraordinary events at Spoleto Festival USA this year, a genial ceremony of storytelling, music, dance, AV projections, and communal empathy.

We all received little pencils and pieces of paper as we entered the hall, so it was no mystery that we would participate. Odile, better known as Kiki, tells us something curious in the early moments about her encounters with both survivors and perpetrators: all of them speak of “we” in addressing their experiences instead of “I,” the more logical first-person.

To break through that defensive emotional distancing, Kiki asked them all to write personal letters to the dearest relatives they lost or, in the case of the perpetrators, the people they killed. Kiki’s collection of these letters, some of which she reads to us, are her Book of Life. Since each of these recalls a different story, it is easy enough for Kiki to weave other elements into the fabric of her show.

One recurring thread is an origin folktale where a leopard calls together the entire animal world and asks them all how they can steal away a piece of the sun from the other side of creation to light up their world of darkness. In succeeding episodes, a mole rat, a vulture, and a wee spider volunteer to be the leopard’s stealthy envoys, tunneling through to the other world, chipping off a piece of sun that won’t be missed, and bringing it back intact to spread the light.

Spread across the stage, four women in amazing multicolored braids on each side of Kiki, are a group of live light-givers, the inspirational Ingoma Nshya (“New Drum” or “New Power” if you don’t speak Kinyarwandan): The Women Drummers of Rwanda. In the wake of the 1994 genocide, a grassroots movement incorporating all of Kiki’s constructive and conciliatory impulses founded the first Rawandan women’s drum circle in centuries – overturning a taboo against women even touching a drum or approaching a drummer.

The group’s name proves to be rather modest, for the women not only pound complex arrangements by Mutangana Mediatrice on their large conga drums, they sing impressively – as soloists or as a chorus – and they also dance, swinging their multicolored braids as part of the choreography or in pure joy. Translations of the songs are projected upstage, where we also see animations that accompany the testimonial letters and the animal fable.

Altogether, I thought that Kiki didn’t read nearly enough letters from The Book to counterbalance all of her charming diversions. Perhaps the most pleasing of these was hearing of her initiative to employ more women in Rwanda, an ice cream shop called Sweet Dreams, staffed entirely by women.

Most intriguing was Kiki’s unique exercise in sharing, when she asked everyone to draw a picture of one of our grandfathers with our pencils and papers. Not at all standoffish, Kiki herself came out into the hall to collect our handiwork, a nice touch. Then she gathered the entire drumming ensemble around her onstage to pick a winner that was shared with all of us, blown up on the projection screen.

The sharing continued as Kiki showed us a sheaf of past winners, one by one. After the show, trays of today’s drawings would be available in the lobby, and Kiki encouraged us to pick up one of these grandfathers as a keepsake on the way out. It was a fine way of underscoring a key point: images and memories of loved ones we have lost are still in our hearts and minds, shareable if we make the effort.

Review: An Iliad at Spoleto Festival USA

By Perry Tannenbaum

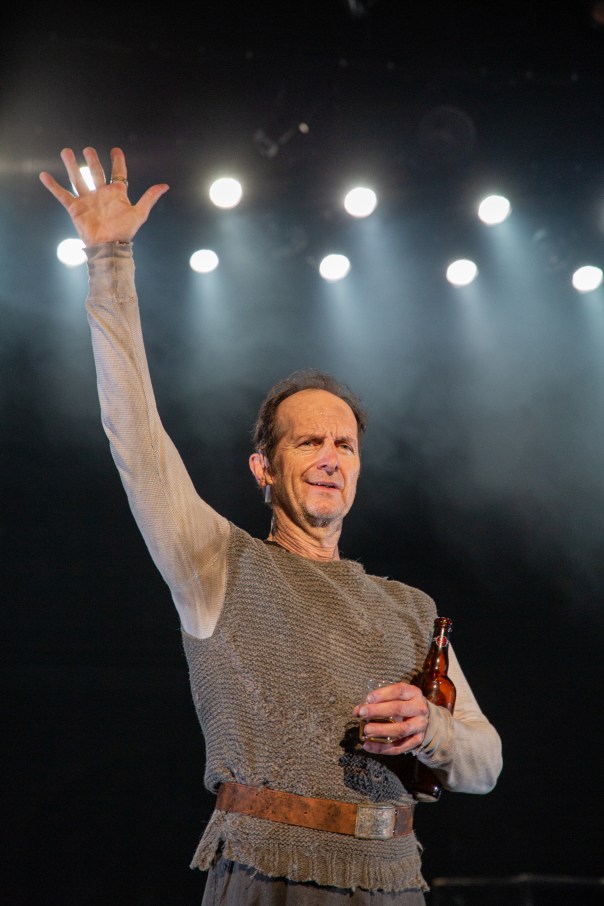

Writer-director Lisa Peterson and writer-actor Denis O’ Hare have chosen well in naming their adaptation of Homer’s epic AN ILIAD. For this Iliad is to be understood as one of many possibilities: one of many ways of retelling the blind poet’s colorful account of the Trojan War, which itself codifies many ancient oral transmissions by the Greek bard, and sadly, one of many wars that can be lamented, bewailed, and memorialized in this way.

There’s a noticeable world-weariness in O’Hare’s demeanor as he enters for his Spoleto Festival USA debut, turns off a downstage ghostlight, and moves it to the wings at the antique Dock Street Theatre as he settles into the storytelling. Clearly in his eyes, it isn’t a story that does credit to mankind.

We quickly learn that Achilles and Hector will be the chief protagonists and adversaries in this distillation. Mercilessly, Peterson and O’Hare zero in on chief Greek personalities, just as Homer did, but with a more concentrated focus on their pettiness and hypocrisy. The war was begun when Hector’s brother, Paris, eloped with the beauteous Helen of Troy, stealing her from King Menelaus of Sparta.

King Agamemnon of Argos, brother of Menelaus, declares war on Troy to avenge his brother’s disgrace, and launches the fabled thousand ships to bring Helen back. O’Hare actually dips into the Robert Fagles translation of Homer to enumerate the kingdoms and the exact numbers of their ships that have sailed the seas with armed soldiers just to settle this domestic squabble.

Yet when we first see O’Hare portraying Agamemnon, nine long years into the 20-year war, the Argive king is refusing to give back a woman he shouldn’t have, despite the fact that the gods have already punished him for his insolence by decimating the entire Greek army with plague. When the Greek general finally relents, he does so by taking Achilles’ woman, Briseis (spoils of a previous war!), in exchange. Achilles’ isn’t pleased at all, but his counter to this indignity is more sullen and tranquil: the greatest champion of the Greeks sits in his tent, refusing to fight.

O’Hare is so focused on the pettiness and selfishness of Achilles that he ignores the impact and implications of his sitdown strike: by sulking on the sidelines, Achilles does as much – if not more – to turn the tide of the war than the deaths of thousands in the plague. That’s how colossally great this warrior so often proves to be in Homer’s telling.

But despite O’Hare’s anti-heroic sentiments, there is no stinting when he arrives at the wrath of Achilles, the Myrmidon king, after Hector has slain his beloved Patroclus. Nor should there be, since “Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles” is the opening plea from Homer to his Muse in Fagles’ translation – and every other – clearly the Bard’s central subject.

There’s a huge payoff for dwelling on Achilles’ rage and his barbaric exultation after he has avenged Patroclus’s killing. The fury of it resonates through the Homeric catalogue that O’Hare inserts into his narrative, a catalogue of wars that have raged around the world since the Trojan War that parallels the Homer’s catalogue of ships that sailed on Troy.

Ultimately, Achilles’ fury and his fearsome rampage are a towering eruption of his hurt pride and the bitterness of his compounded losses. Agamemnon surely hasn’t appeased him, and his best friend Patroclus found no way to end his sulking. Yet when he spirals out of control, still furious after wreaking his revenge, it is the grieving King Priam, Hector’s aged father, who finally calms Achilles down and returns him to civility.

O’Hare crafts his storytelling, referencing our pandemic sufferings and the war in Ukraine along the way, in a manner that augments the dignity and poignancy of Priam’s supplications – making us understand how deeply the old king must reach to stir Achilles’ humanity and steer him back toward reason.

The magic of this moment is in the commonality of the grief that Achilles and Priam can share. It is a grief that men have perpetrated and suffered forever. We shake our heads sadly over how devastatingly hurtful and heartbreaking it all is – and how utterly senseless and stupid.

By Perry Tannenbaum

With so many theatre, dance, opera, jazz, orchestral, choral, and chamber music events to choose from – more than 300 artists from around the world, streaming in and out of Charleston over 17 days (May 26 through June 11 this year) – planning a dip into Spoleto Festival USA is always a challenge. Even Spoleto’s general director, Mena Mark Hanna, struggles to prescribe a strategy, as hesitant as a loving mother of 39 children to pick favorites.

“My suggestion for a first-time participant,” he says, sidestepping, “would be to see two things you like and feel comfortable about seeing, maybe that’s Nickel Creek (May 31-June 1) and Kishi Bashi (June 3), and two things that are really pushing the envelope for you. So maybe that’s Dada Masilo (June 1-4) and Only an Octave Apart (June 7-11).”

Nicely said. Only you can easily take in the first three events Hanna has named within three days, but you’ll need another four days before you can see singer-songwriter phenom Justin Vivian Bond and their monster opera-meets-cabaret-meets-pop collaboration with countertenor sensation Anthony Roth Costanzo. If you happened to see the recent Carol Burnett tribute on TV, the cat is out of the bag as far as what that will sound like, if you remember the “Only an Octave Apart” duet with opera diva Beverly Sills – recreated for Carol by Bernadette Peters and Kristin Chenowith.

What it will look like can be savored in the Spoleto brochure.

The giddy Bond-Costanzo hybrid is one of the key reasons that my wife Sue and I are lingering in Charleston through June 9. Equally decisive is the chance to see jazz legends Henry Threadgill (June 6) and Abdullah Ibrahim (June 8), the Spoleto Festival USA Chorus singing Thomas Tallis’ Spem in alium (June 7-8),and Jonathon Heyward conducting Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique (June 9).

One other irresistible lure: the opportunity to see Maestra Mei-Ann Chen conduct Antonín Dvořák’s New World Symphony (June 7), along with works by Florence Price and Michael Abels – less than four months after her scintillating debut with the Charlotte Symphony.

Abels, you may recall, teamed with Rhiannon Giddens last year in composing Omar, the new opera that premiered at Spoleto – after an epic gestation that spanned the pandemic – and won the Pulitzer Prize for Music earlier this month. It was a proud moment for Spoleto, for Charleston, and for the Carolinas. For Hanna, it was an extra special serendipity to help shepherd that work to completion.

“I mean, it’s kind of incredible,” he explains, “to be someone who comes from Egyptian parentage, speaks Arabic, grew up sort of fascinated by opera and stage work and spent their career in opera and was a boy soprano – to then have this opportunity to bring to life the words of an enslaved African in Charleston, South Carolina. And those words are Arabic!”

We may discern additional serendipity in the programming of this year’s opera, Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti’s Vanessa (May 27-June 10), which garnered the Pulitzer in 1958. Revived at Spoleto in 1978, the second year of the festival – with festival founder Menotti stage directing – the production was videotaped by PBS and syndicated nationwide on Great Performances, a huge boost for the infant fest. That revival also sparked a critical revival of Barber’s work.

Omar was the centerpiece of a concerted pushback at Spoleto last year against the Islamophobia of the MAGA zealots who had dominated the headlines while the new opera was taking shape. Vanessa is part of what Hanna sees as a subtler undercurrent in this year’s lineup, more about #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, and the repeal of Roe v. Wade.

“I want there to be a kind of cohesiveness without necessarily us being able to see what the theme is,” Hanna reveals. “If there is something that unifies a lot of these pieces, it’s about understanding that we are telling stories from our past, some of them the most ancient stories that we have in our intellectual heritage. We are looking at these stories with a different sense that takes on the reverberations of today’s social discourse.”

Among other works this season at Spoleto that Hanna places in his ring of relevance are An Iliad (May 26-June 3), a one-man retelling of Homer’s epic featuring Denis O’Hare; Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (June 5), as an orchestral concert and the inspiration for Masilo’s The Sacrifice; Helen Pickett’s new adaptation of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible for Scottish Ballet (June 2-4); and A Poet’s Love (May 26-30), a reinterpretation of Robert Schumann’s Dichterliebe song cycle by tenor/pianist Jamez McCorkle, who played the title role in Omar last year – with stagecraft, shadow puppetry, and projections by Miwa Matreyek.

“Going back to the Trojan War, An Iliad is as much about war and plague then as it can be today with the reverberations of Ukraine and the pandemic,” says Hanna. “Vanessa, is reinterpreted here through the lens of a remarkable female director, Rodula Gaitanou. The cast is just killer: You have Nicole Heaston as the lead with Zoe Reams and Edward Graves and Malcolm McKenzie and Rosalind Plowright, just a world class cast at the very, very top. And it’s also really cool to see these roles, which are traditionally sung by Caucasian people, being sung by people of color.”

Aside from the recurring motif of reclusion, so vividly resonant for all of us since our collective pandemic experience, Hanna points to a key turning point in the opera. Menotti left it mysterious and ambiguous in his libretto at a key point when Vanessa’s niece, Erika, either has a miscarriage or – more likely – an abortion.

For Hanna, that brings up an important question: “What does that mean now when we are looking at a renewed political assault on female autonomy? So these stories take on new messaging, new reverberation in 2023. And we need to retell these stories with the new lens of today.”

Especially in the Carolinas.

Long accompanied by a more grassroots and American-flavored satellite, the Piccolo Spoleto Festival, Menotti’s international arts orgy has taken a long, long time to shed its elitist mantle. Now it is moving forcefully in that inclusive direction with a new Pay What You Will program, offering tickets to about 20 performances for as low as $5 – thanks to an anonymous donor who is liberating about $50,000 of ticket inventory.

Hanna brought this exciting concept to the unnamed donor, hasn’t talked to him or her or them – yet – about sponsoring the program in future years, but he is pledging to continue it regardless.

“What art can do is endow you with a new experience, a transformational experience that you did not have before you took your seat,” he says. “It can help create an understanding of another side that is normally seen by one perspective as socially disparate, as highly politicized, as a discourse that’s just way too far away. Art can break down that barrier through the magic and enchantment of performance. To me, having those artists onstage, representative of a demographic we wish to serve, only takes us so far. We also have to lower the barrier of entry so that we can actually serve that demographic.”

Kishi Bashi not only continues Spoleto’s well-established outreach to Asian culture, he also typifies the more hybrid, genre-busting artists that Hanna wants to include at future festivals.

“We want to try to find these artists that are like pivot artists, who occupy these interstitial spaces between dance and theater and classical music and jazz and folk music,” Hanna declares. “And Kishi Bashi is one of those. He plays the violin on stage. He has all of these violinists on stage with him, but it’s this kind of strange, hallucinatory, intoxicating music that’s like somehow trance music and Japanese folk music, but using sort of Western classical instruments. Yet it’s very much in an indie rock tradition as well.”

Other wild hybrids include Leyla McCalla (May 26), the former Carolina Chocolate Drops cellist who blends Creole, Cajun, and American jazz and folk influences; Australian physical theatre company Gravity & Other Myths (June 7-11), mixing intimate confessions with acrobatics; Alisa Amador (June 7), synthesizing rock, jazz, Latin and alt folk; and the festival finale, Tank and the Bangas (June 11), hyphenating jazz, hip-hop, soul, and rock. Pushing the envelope in that direction is exciting for Hanna, and he promises more of the same for the ’24, ’25, and ’26 festivals.

Until the Pulitzer win, the year had been pretty rough on Hanna, losing Geoff Nuttall, the personable host of the lunchtime Chamber Music Series at Dock Street Theatre. Nuttall was the artist who convinced Hanna to come to Spoleto. At the tender age of 56, Nuttall had become the elder of Spoleto’s artistic leadership when he died, beloved for his style, wit, demonstrative fiddling, and his passionate advocacy of the music. Especially Papa Haydn.

The special Celebrating Geoff Nuttall (May 26) concert will gather his close friends and colleagues for a memorial tribute at Charleston Gaillard Center, including violinist Livia Sohn, cellist Alisa Weilerstein, countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo, tenor Paul Groves, pianist Stephen Prutsman, and surviving members of the St. Lawrence Quartet. The occasion will be enhanced by the Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra and Atlanta Symphony’s Robert Spano – plus other guests soon to be announced.

Hosting chores for the lunchtime 2023 Chamber Music series, spread over the full festival, 11 different programs presented three times each (16 performances at 11:00am, 17 at 1:00pm) will be divvied among vocalists and instrumentalists who perform at the Dock. It was totally inappropriate, in Hanna’s eyes to replace Nuttall onstage this year, but he will begin to consider the charismatic violinist’s successor during the festival and into the summer. Hanna assured me that the player-to-be-named later will be a performer who participates in the musicmaking.

Continuing on the trail blazed by Amistad (2008), Porgy and Bess (2016) and Omar, Hanna wants to place renewed emphasis on the Port City and its African connection. It must run deeper than seeing Vanessa delivered by people of color.

“Charleston was the port of entry for the Middle Passage,” Hanna reminds us. “And Charleston has at its core an incredibly rich Gullah-Geechee-West African-American tradition that is part of the reason this is such a special, beautiful place to live in with its baleful history. So I think that you see that this year, you see that with Gakire Katese and The Book of Life (June 1-4), you see that with Dada Masilo and The Sacrifice, you see that with Abdullah Ibrahim and Ekaya.”

Resonating with the brutalities of Ukraine, Ethiopia, and Syria on three different continents, the US Premiere of Odile Gakire Katese’s The Book of Life may be the sleeper of this year’s festival, crafted from collected letters by survivors and perpetrators of Rwanda’s 1994 genocide and performed by Katese, better known as Kiki. “After the unthinkable, a path forward,” the festival brochure proclaims. The finding-of-hope theme will be underscored by music created by Ingoma Nshya, Rwanda’s first-ever female drumming ensemble, founded by Katese.

“Kiki is engaging with how a country tries to reconcile with its recent, terrifically horrific past of the Rwandan genocide as someone who grew up Rwandan in exile. You see that in the work of Abdallah Ibrahim, who was really one of the great musicians of the anti-apartheid movement, who composed an anthem for the anti-apartheid movement, was in a kind of exile between Europe and North America in the 80s. And then when he finally came back to South Africa for Nelson Mandela’s inauguration, Nelson Mandela called him our Mozart, South Africa’s Mozart.”

Marvelous to relate, you can hear more of South Africa’s Mozart this year at Spoleto Festival USA than Vienna’s Wolfgang Amadeus – or Germany’s Ludwig von Beethoven. That’s how eclectic and adventurous this amazing multidisciplinary festival has become.

See for yourself.

Review: Only an Octave Apart at Spoleto Festival USA

By Perry Tannenbaum

As we were recently reminded in a special CBS celebration of Carol Burnett’s 90th birthday, “Only an Octave Apart” was first sung by Burnett and soprano Beverly Sills in 1976 on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera. That was a year before the first Spoleto Festival USA was first presented in Charleston, South Carolina. So the full-length CD recorded by Anthony Roth Costanzo and Justin Vivian Bond, followed by the full-length Only an Octave Apart stage show, now live at Dock Street Theatre, is a fascinating look at how much things have changed – and how much they haven’t – since the crown jewel of New World arts festivals was still in embryo.

When Burnett and Sills staged their duet, the New Met was still a pre-teen at the Lincoln Center, and their encounter was mostly about the comical incongruity between network TV and opera, pop and high culture, a sweet voice that could benefit from amplification and one that gloriously blared, and how delightfully these vast differences could be bridged. Julie Andrews subsequently filled in at Sills’ spot opposite Burnett, somewhat altering the chemistry and disparity, and Bernadette Peters recently teamed up with Kristin Chenoweth when Burnett was feted.

Costanzo and Bond are clearly in a different mold, and their show produces a different, more risqué vibe. The younger Costanzo is gay, and the elder Mx Bond is trans, so the chemistry is brasher and bolder, and after engagements in Brooklyn and London, they can jubilantly proclaim that this is the show’s first foray “into a Hate State.” Nothing remotely as mundane as network TV is in this cross-cultural rendezvous. Now we have edgy cabaret encountering baroque-era opera, drag pitted against high culture, and a sweet countertenor mixing it up with a non-binary baritone who seem to have razor blades in their larynx.

Watching Octave after attending Bond and Costanzo’s joint interview with Martha Teichner the previous afternoon was a lot like sitting in an echo chamber, since much of their early patter was about ground already covered: how their show came into being and their mutual admiration. As the lines about the Hate State affirm (along with Bond’s repeated quips about performing at the “Stiletto Festival”), there is flexibility built into the script, a certain amount of spontaneity and improvisation for the cabaret divx to feel free and a certain amount of structure and recognizable landmarks for Costanzo to feel secure and oriented.

Of course, those who came to the show after listening to the Octave CD had a different echo-chamber experience. For me, the anticipation of what songs these two flamboyant performers would sing together – aside from the title song, of course – was genuinely suspenseful.

Even though I’d seen publicity shots, the outré Jonathan Anderson costumes turned out to be more of a wallop. The first pair of full-length gowns, with their pointy projections, could double as writing desks! Although they were seriously overmiked, I wanted to hear much more of Bond at a softer volume, for Costanzo has been a staple at my visits to Spoleto for over 20 years, long before his Akhnaten apotheosis at the Met.

No wonder, then, that the most satisfying duet for me – and everyone else in the room – was the fun-filled mashup where Bond sang the novelty pop hit, “Walk Like an Egyptian,” while Costanzo actually did that, crossing in front of Bond as he reprised the quacking gibberish Philip Glass wrote for him when he portrayed the ancient Pharaoh. Naturally, the exuberant Bond wanted to get a piece of that quacking action themselves, and Costanzo completed the role reversals by singing the pop trinket as high as it has ever been sung.

Less successful role-reversal silliness came earlier in the show when Costanzo stationed himself behind the curtain so Bond could feel like the bewitching Carmen as they lip-synced the countertenor’s rendition of the “Habanera.” More to my liking was Costanzo’s singing of both roles in an Orpheus and Eurydice duet by Christoph Willibald Gluck, underscoring what he had told us the day before in the Teichner interview, that he had started his operatic career as a tenor.

Yet Costanzo confided in the scripted format of Octave that he found the countertenor pre-1750 lane too narrow to stick strictly with an operatic career, and Bond sagely confirmed the enormity of their co-star’s ambitions. Perhaps this was what impressed me most about Bond and their rapport with Costanzo. Speaking barely above a Lauren Bacall purr, they could interrupt the ebullient Costanzo in mid-gush and not a word of their quips or barbs would go unheard.

Before the rousing “Egyptian” climax, there are more serious and affirming interludes that help set up this zany showstopper. Costanzo sings Franz Liszt’s “Über Allen Gipfeln Ist Ruh,” based on Goethe’s valedictory poem; Bond brings tenderness and a very timely pathos to “I’m Always Chasing Rainbows,” and he only goes slightly overboard on the loneliness of “Me and My Shadow.” The duet on Patrick Cowley’s “Stars” was the most consistently powerful of the night, but only because their rendition of “Under Pressure” by David Bowie and Queen – some notably operatic rockstars – veered into “Vesti la giubba” from Pagliacci.

In the midst of the COVID pandemic, Only an Octave Apart started off as a recording project that would keep the artists busy, productive, and connected. But the stage version of OCTAVE continues to benefit its stars and expand their skill sets. While Costanzo has acclimated himself to venturing off-book onstage, he has noticed that his newfound comfort and relaxation have carried over into his singing. His hunched-up shoulders have eased down, and one night, he discovered that he had sung three notes higher than he had ever reached before.

Naturally, there were a few Hate Staters in the audience who had blundered into the Dock Street Theatre not knowing just how far apart from their comfort zones this show would be. They walked out at various points, exhibiting differing levels of tolerance that might be clinically analyzed. More of us were uplifted by the audacity and pride we saw onstage – and by the overwhelming acceptance throughout the hall.

Every so often, we were reminded of Taylor Mac’s triumphant return to Charleston in 2011 after a previous conquest, when he proclaimed, “This is my festival now, bitches!” and renamed it The Stiletto Festival. It is rather pitiful that America has regressed at least as much as it has progressed since then. That made Only an Octave Apart more than a heartening display of courage and lighthearted determination from Costanzo and Bond. In a Hate State flooded with MAGA maniacs, this was a rainbow of love.

By Perry Tannenbaum

Baked into many great American plays is the notion that dreaming big, striving for the golden apple of success, is a kind of latter-day hubris – sure to be tragically quashed and beaten down. Walter Lee Younger in Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun was a grim example of such a tragic hero, dreaming of owning a liquor store in Chicago during the 1950s. It was hard for me not to think of Walter Lee’s beatdown – and paradoxically, the soaring success of Sidney Poitier, the breakthrough actor who portrayed him – as Dominique Morisseau’s Detroit ’67 unfolded at Theatre Charlotte.

Tautly directed by Ron McClelland and superbly designed by Chris Timmons, Morisseau’s work is darker and bloodier than Hansberry’s classic but emphatically more hopeful. Even with the background of the Detroit race riots of 1967, the pride of Black culture never leaves our eardrums for long as a clunky old record turntable, replaced by a slicker 8-track player and a pair of bookshelf loudspeakers, cranks out the hits of Motown’s famed music machine.

Come on, David Ruffin! The Temptations! Smokey Robinson and The Miracles. Mary Wells. Martha and the Vandellas. The Four Tops. Gladys Knight and the Pips. Marvin Gaye.

Morisseau’s protagonist, Lank, and his sister Chelle are trying to upgrade their unlicensed basement bar so that it will become more competitive with other after-hours speakeasies – when Sly, Lank’s best friend and a numbers runner, offers him an opportunity to buy into a legit bar. History lesson: a police raid on one of the unlicensed bars Lank and Chelle are seeking to emulate triggered the Detroit riots, the worst in 20th century America until another shining example of policing, the Rodney King riots in LA, eclipsed them in 1992.

While the riots rage and Michigan guv George Romney is calling in the National Guard, Lank and Sly are striving to scout out their hoped-for property and close on a deal – against Chelle’s wishes. Meanwhile, a second hubris slowly develops as Lank shelters a lovely white woman, Caroline, who has been battered and is mysteriously linked with the white underworld. She’s actually in more mortal danger than Lank.

Despite mutual suspicions, Caroline and Lank are drawn to each other. But they bond over Motown music, and they are both capable of busting a dance move.

The rioting in the Motor City was a prelude to the Black Power demonstrations at the Mexico City Olympics in 1968. We can also view them as a precipitating factor leading to the pride-filled Summer of Soul celebrations in Harlem and the rapprochement between the races on the musical scene that accelerated at the gloriously chaotic and inspiring Woodstock Festival of 1969, for so many of us the decade-defining event of the ‘60s.

So Detroit ’67 not captures a city in turmoil, it echoes the prime crosscurrents of that era, the struggle of Black people for their legitimate rights, the backlash from white people and government, and the mainstreaming of Motown as it breaks into pop culture. And by the way, Sidney Poitier’s To Sir With Love and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner were both released in 1967. The question of whether Blacks were making significant progress, suffice it to say, was very much up in the air as we watch this action at the Queens Road barn.

Running an underground business together, Lank and Chelle are more advanced in their autonomy, street smarts, and connections than Walter Lee and his sister Beneatha were, still living under their mother’s roof with Walter Lee’s wife and child. Pushback against Lank’s feasible but difficult dream comes entirely from Chelle, who can realize deep down that continuing to run an illegal operation is also a risky choice.

Morriseau, McClelland, and Shinitra Lockett, making her acting debut as Chelle, all seem to have made this same calculation. So Lockett seems noticeably more vehement in her opposition toward Lank’s romance with Caroline than in her objections toward his business venture with Sly. On the business end, Sly’s persistence and charm in pursuit of Chelle’s affections bodes well for his deal-making prospects, another softening factor, for Lockett occasionally shows us that the slickster is making headway.

Because we see Graham Williams is so composed and self-assured as Sly, we can begin to see Lank as acting audaciously and responsibly. Yet there’s enough shiftiness mixed with Williams’ confidence for us to retain Walter-Lee misgivings about their venture, especially when the riots and the National Guard are thrown into the mix. Devin Clark, one of Charlotte’s best and most consistent performers for more than nine years, gives Lank a stressed and urgent edge. He’s not as regal and commanding as he was portraying Brutus last summer, but he’s far more spontaneous and charismatic.

Chandler Pelliciotta, in their Theatre Charlotte debut, brings a bit of shy diffidence to Caroline that meshes well with her story. Her worldly swagger has obviously been dealt a severe blow as she wakens, bruised and disoriented, in the basement of a Black man’s home she has never seen before. While Lank is drawn to her and wishes to protect her – we aren’t always sure which of these impulses is in play – Chelle has a couple of good reasons to wish her gone.

Not the least of these is the trouble Caroline is in with people who have battered her with impunity. The trouble might pursue her and find her at this fledgling underground speakeasy. It’s an awkward position tinged with risqué allure, but Pelliciotta’s performance leans more into the awkwardness, their glamor far less in the forefront than their fearfulness – for Caroline herself and for her protectors.

You can probably name 15 Black sitcoms that have characters like Chelle’s mismatched chum, Bunny: sexy, flirty, quick-witted, and imperturbable. Germôna Sharp, in her bodacious Charlotte debut, takes on her life-of-the-party role with gusto and sass. Sharp makes sure we’re not getting a PG-17 version of Bunny: slithery, regal, carnal, and militantly unattached. She will dance with anybody – Lank, Sly, or Chelle – but not for long, totally neutral amid the sibling fray.

Costume designer Dee Abdullah helps turn on the glam, more flamboyant for Sharp and more elegant for Pelliciotta. Morriseau withholds from her characters any sententious awareness that they are standing at Ground Zero of anything historic, now or in the future, but she clearly wishes that awareness on us. A distinctive black fist is prominently painted on one of the basement walls, right above the record player and the 8-track, and its presence is meaningfully explained.

Nor should we consider evocations of Hansberry’s classic urban drama as accidental. Morriseau’s script tells us that her protagonist’s name, Lank, is short for Langston. It cannot be a coincidence that the poet Langston Hughes wrote “Harlem,” the iconic poem from which Hansberry drew the title of her masterwork, A Raisin in the Sun.