Review: Julius Caesar from Free Reign Theatre Company

By Perry Tannenbaum

It’s an odd juxtaposition, that’s for sure. In reviving Julius Caesar, Free Reign Theatre Company has taken what is arguably Shakespeare’s most urban tragedy and transported it to Historic Rural Hill, a 15-minute drive from the nearest town, suburban Huntersville. Coming by way of I-77 and the I-485 beltway to the Sunday matinee, we may have seen one traffic light after exiting the highways and entrusting our destiny to Google Maps.

When you arrive, you turn off a narrow winding paved road onto a narrower, arrow-straight gravel road that carves through a grassy rise, two rustic buildings looming at the top. On a sunny Sunday afternoon, the simple colors and weathered wooden structures of the place reminded me of Christina’s World at first blush, Andrew Wyeth’s masterwork. Even as we parked, it seemed unlikely that either of these buildings could be a theater. The shed at our right seemed too small, and the barn-like building in front of us seemed to be serving a different purpose.

The sheer number of cars in the makeshift lot gave me the sinking feeling that we were in the wrong place. The family emerging from another car did not have the look of theatergoers heading to see Julius Caesar. God help us.

Moving closer, I still felt that the old building might be serving as a café, with customers or picnickers mulling around under a ramshackle awning at the side. Wide double doors facing us didn’t seem to be in use, so we headed to the other side of this barn, where things finally began to make sense.

A long file of food trucks was aligned down the slope at the other side of the rise, explaining the phenomenal number of cars that had parked. The doors at this side of the big barn proved to be the entrance to Free Reign’s makeshift theater, extending all the way to the other end of the building. Actually, this theater extended beyond its rear wall – for those people who seemed to be dining al fresco on the other side were really Free Reign’s acting troupe.

Most of the backstage maneuvering in this production actually happens outdoors, with just a narrow corridor behind the temporary stage devoted to entrances and exits. Stage manager Megan Hirschy already had the comings and goings of the 17-person cast running with admirable precision by the time we witnessed the fourth performance, but could she really do it without a stash of Tylenol or other medicinals?

We couldn’t have mistaken the Roman citizens, senators, tribunes, tradesmen, or Caesar for picnickers if costume designer Heather Bucsh – and director Robert Brafford – had opted for the ancient attire from Italian fashionistas that was trendy in March of 44 B.C. Judging by the half dozen Caesars I’ve seen since the turn of the millennium (in Oregon, Canada, High Point, and Charlotte), it would be a novel idea these days to revert to authentic dress.

Not surprising. The tensions in this tragedy between representative government and autocracy, freedom and slavery, those in power and those scheming to overthrow them – all of these resonate with us more readily in the New World than the dynastic Old-World struggles and power grabs that typify Shakespeare’s histories and dramas. For some odd reason, the approval of the common folk seems to matter in Julius Caesar, and that naturally appeals to Americans.

Because Shakespeare views Caesar, Mark Antony, and Marcus Brutus with such admirable objectivity, it has always been fairly easy for actors and directors to tip the scales one way or the other – to make this Caesar’s tragedy or Brutus’s – or to balance Brutus equally with his adversaries, making them both tragic victims. In Elizabethan days, Shakespeare’s contemporaries would have been more likely outraged by any opposition or treachery against a monarch. For generations, Antony’s funeral speech would be memorized as if it were gospel.

Today’s audiences are more cognizant of Antony’s cunning. The laughter that rang out at Historic Rural Hill as Ted Patterson delivered the famed oration was partially directed at Antony for his transparent manipulativeness. Mostly, it was aimed at the notion that “We, the people” would fall for it. We would need to be very rustic indeed for that to happen.

Patterson lets us see, with a choice expression or three, how Antony marvels at how easy it is to sway a Roman mob, not exactly the same valiant and vulnerable romantic hero we find in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra. That’s enough to ensure that our sympathies will lean toward Brutus, but Russell Rowe gives us an extra nudge as Caesar, a little bit more arrogant, pompous, and egotistical than we might expect from a benevolent ruler – and a little less tender and empathetic towards his wife, Calpurnia, who pays more heed to soothsayers and bad dreams.

Offstage, Caesar is rejecting a crown three times during the opening scenes, but we actually see Brutus rebuffing Cassius when he repeatedly urges taking action, fearing that Caesar will relent, accept a throne, and become invincible. Both of the main adversaries show character, but Devin Clark as Brutus is clearly the gentler of the two. With just spare scenery at his disposal, Brafford shrewdly distinguishes between the dignity of Caesar’s household and the humbleness of Brutus’s at the other end of the stage.

There is also a palpable difference between the wives. Lauren Duckworth is regal as Calpurnia rather than adoring: when she counsels her husband against venturing out to the Capitol on the Ides of March, we assume that she’s angling to reign for decades as Empress of Rome. Alexandria Creech is definitely more submissive as Brutus’s wife, Portia, more intimate and seductive.

Both men give in to their wives, but Caesar’s yielding to Calpurnia is only temporary, largely because Cal has overstepped while Portia asks for less. More to the point, both leaders give in to their most potent political allies, Caesar finally deigning to accept a crown from Antony and The Senate, Brutus agreeing to join Cassius and his cronies in their assassination plot.

Both men give in to their wives, but Caesar’s yielding to Calpurnia is only temporary, largely because Cal has overstepped while Portia asks for less. More to the point, both leaders give in to their most potent political allies, Caesar finally deigning to accept a crown from Antony and The Senate, Brutus agreeing to join Cassius and his cronies in their assassination plot.

Off my radar since her college days 12 years ago, Chelsea Hunter is instantly sensational as Cassius. Along with Patterson, Rowe, and Clark, Hunter has one of the strongest voices onstage, so her Cassius is formidable and authoritative as well persuasive – perhaps even intimidating, notwithstanding Clark’s impressive sangfroid. What seems strange in this modernized Caesar, with its colorblind and gender-blind casting, is that Brafford didn’t cross a final frontier and change the pronouns of the text to suit his players.

Two thousand years after Caesar’s death – and 300 after Shakespeare’s – it’s perfectly ordinary to find women scheming and mixing it up with fellow politicos. So why hesitate?

Brafford’s reluctance became most problematic and comical with Jess Johnson’s unmistakably feminine – and gossipy – take on Casca. Giving Cassius and Brutus the lowdown on Antony thrice offering the crown and Caesar turning it down with increasing reluctance, Johnson was repeatedly flapping open an oriental fan to punctuate her narrative. This mode of exposition was pretty hilarious and hard to quibble with, particularly in recounting what we know, we know, we know.

Johnson’s demonstrative antics were also handy at a matinee on a hot afternoon when the building’s AC was waging war against the heat outside, victorious against the torrid temperature but also against all but the loudest voices. Conditions for hearing all the actors and getting the full impact of the lighting are undoubtedly better at evening performances, and a boost for Great Caesar’s Ghost. But whoever had his or her hand on the switch should be coping with cooler weather next Sunday’s matinee – and better aware of the AC overkill this week that had some members of the audience rubbing their arms or shivering.

Less AC would be a win-win for noise and comfort.

The view outside at Historic Rural Hill is likely pretty hectic during a performance, for more than half the cast is doubling, tripling, or more to play all the roles that Shakespeare prescribed. Brafford himself took on four roles aside from directing. My favorites among these platooned players were Jonathan Caldwell as the sassy Cobbler in the opening scene, Kristin Varnell as the spooky Soothsayer, and the inimitable David Hensley as Lucilius, the slimeball who hilariously impersonates Brutus in the heat of battle.

Best of all, though, is the chameleonic Katie Bearden, who plays no fewer than five roles, including Decius Brutus, surely the most underappreciated role in all of Shakespeare. For Decius undoes Calpurnia’s persuasion, reinterprets her prophetic dream, and with sly flattery convinces Caesar to come on down and accept the crown from The Senate. These are feats of dissembling and oratory worthy of Mark Antony, with no less impact on Roman history.

What was conspicuous for me in 2022 watching Julius Caesar – what I overlooked when I previously saw it at Spirit Square in 2014 – was the complete lack of dialogue between Brutus and Caesar before differences between them were settled with violence. Very much like America now and then, only so much more obvious today.

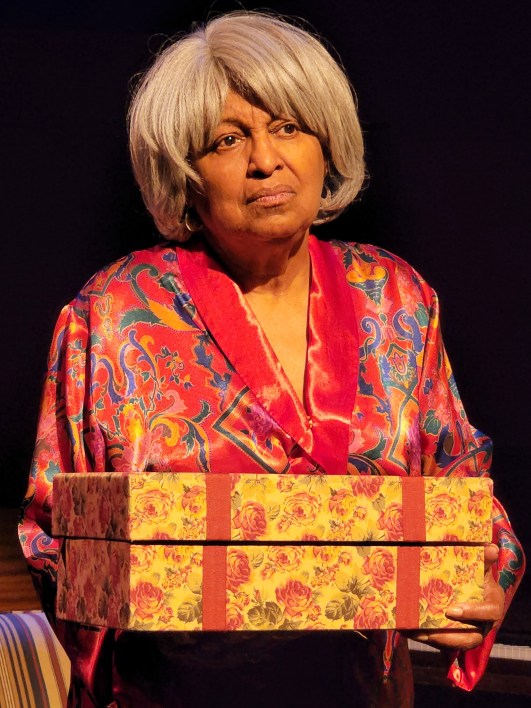

![Noises-116[4]_edited-1](https://artonmysleeve.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/noises-1164_edited-1.jpg?w=604)

Like me, audiences are so used to seeing this story of grim understanding and growth through the eyes of a little girl, Finch’s tomboy daughter Scout. They will likely be shocked to discover that Sorkin is far more interested in the lessons Atticus learns – and the lessons we still haven’t learned as a society. In the wake of 2020 and the bitter fruit of #BlackLivesMatter, Sorkin’s Mockingbird 2.0 offered some fortified pushback from the Finches’ housemaid Calpurnia, scolding Atticus for his oft-expressed bromides that we should respect everyone since everyone has some good inside of them.

Like me, audiences are so used to seeing this story of grim understanding and growth through the eyes of a little girl, Finch’s tomboy daughter Scout. They will likely be shocked to discover that Sorkin is far more interested in the lessons Atticus learns – and the lessons we still haven’t learned as a society. In the wake of 2020 and the bitter fruit of #BlackLivesMatter, Sorkin’s Mockingbird 2.0 offered some fortified pushback from the Finches’ housemaid Calpurnia, scolding Atticus for his oft-expressed bromides that we should respect everyone since everyone has some good inside of them.