Review: how to make an American Son at Barber Theatre

By Perry Tannenbaum

Beyond the first two capital letters ever used by playwright christopher oscar peña in any of his titles, peña injects a joke or two into his newest, how to make an American Son. Within a few minutes, we learn that Mando, the father of the title character, Orlando, doesn’t have the slightest interest in parenting. Mentoring or shaping Orlando as he journeys from childhood to adulthood seem to have been forgotten, replaced by a compulsion to provide him with the best that money can buy.

And then by setting limits on what the kid buys on Dad’s credit. Not so easy when you haven’t been concerned with parenting or tough love for the past 16 years.

We also learn that Mando, the founder/CEO of a successful janitorial firm, is a Honduran immigrant and his son was born in the US. So Orlando is an American! In the crudest sense, the fabrication of our young antihero was successfully consummated in dimly-lit intimacy.

Clearly, peña is working with a more nuanced definition of what an American truly is, pursuing a more nuanced answer on how one is made. Orlando is gay, piling fresh levels of challenge and difficulty on his quest to reach a feeling of belonging while making that quest more widely relatable to any member of a family with someone who has come out. Mom and Dad, to their credit, have accepted their son’s sexuality, though Mom (never seen) prefers that Orlando date Latinos.

Whether or not he has been bolstered by his parents’ liberal leanings, Orlando is fairly strong-willed. Yet he also has that second-generation softness of suburban children who take their money and privilege for granted, never needing to stoop or get down on his knees to clean a toilet at home or at work. We get different perspectives as new characters take us from Mando’s office to Orlando’s elite school, the interior of a schoolmate’s car, and the lobby of Mando’s most valuable client.

Toss in a careful, diligently hard-working immigrant, who reflects Mando’s work ethic more faithfully than his son, and you can see why peña’s piece appeals so strongly to Common Thread Theatre Collective. Formed last summer by theatre faculty at Davidson College and North Carolina A&T University, the nation’s largest HBCU, Common Thread pushes back against the top-down power dynamic of most professional companies. The Collective seeks to include rather than exclude perspectives of women, LGBTQ+ artists, and artists of color while highlighting today’s most critical issues.

At Barber Theatre, on Davidson’s liberal arts college campus, it’s safe to say that immigration, class divisions, and homophobia fit the bill. White folks aren’t banned from this conversation, but they comprise only one-third of peña’s cast and get an even smaller cut of the stage time. There’s a breezy lightheartedness at the core of Mando’s attempts to check Orlando’s extravagances – a new leather bag for school, tickets to a Madonna concert, and an impulse purchase of Rage Against the Machine tickets to impress the white schoolmate he’s hoping to date.

Comedy lurks in the details because Orlando can run circles around his dad with his tech savvy while he remains so self-centered and immature. A native Honduran who has assimilated more thoroughly than Mando, Rigo Nova brings a streetwise authenticity to this gruff businessman even though has chosen a more urbane path for himself. He makes Mando a juicy target for his son’s slights and barbs, only adding more to the impact of his own thrusts with his scarcely filtered vulgarity.

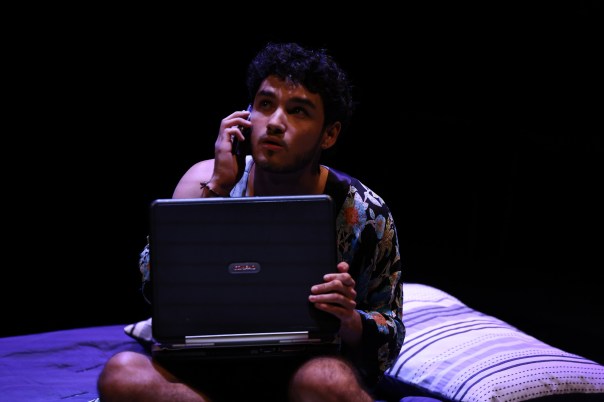

Directing this play in her Metrolina debut, Holly Nañes calls for a nicely calibrated mix of shock, resentment, curiosity, and cool from Nicolas Zuluaga as Orlando when his dad finally sheds his customary benevolence and test-drives the idea of punishment. There are no onsets of diligence, penitence, or heightened seriousness in Zuluaga’s demeanor as he dons a janitorial uniform for the first time in his life. Nor is there any childish pouting or seething resentment as he’s paired up with Rafael, the lowly immigrant.

That breeziness while playing with fire sometimes reminded me of Athol Fugard’s Master Harold in his insouciant superiority; at other times, when seducing Rafael, Curley’s wife from John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men came to mind – an undertow of foreboding as Orlando’s differences with Rafael mirror those he has with his dad. Zuluaga’s almost slothful dominance is nicely complemented by Richard Calderon’s wary and subdued debut as Rafael. He isn’t busting his butt either as he engages Orlando, but he’s working rather than slacking. We can see what Rafael has been through and that he knows the drill.

Striving to get over on Sean, the school jock and Rage Against fanatic, Orlando instinctively drops his cool superiority. We surely see that Logan Pavia as Sean is playing him, ruthlessly confident that he can get what he wants. Maybe Pavia’s audacity shocks you anyhow. The same sort of flipflop happens when Mando shows up Dick’s office, hoping his most-valued client will renew his contract.

We don’t see Rob Addison as Dick until late in the action, and it might have helped a little if we’d gotten to know the white plutocrat better. For this is Addison’s only scene, arguably the most explosive scene of the night as two generations of whites and Hispanics square off. A second blowup afterwards, registering somewhat less on the Richter scale, happens when Mando peeps in on his son and Rafael at precisely the wrong moment.

Stacy Fernandez as Mercedes, newly promoted to become Mando’s general manager, doesn’t witness either of these blowups – or Orlando’s humiliation in Sean’s car. That’s a double humiliation for Orlando because his dad has paused his promise to buy him a car. Without these contexts, Mercedes has a radically different perspective on how to make an American son than the one taking shape for Orlando and his dad. Fernandez gets the opportunity to express this bitter viewpoint in a blowup of her own, and she does not misfire – what she sees, we must acknowledge, is no less valid than what the men see.

Slick and antiseptic, Harlan D. Penn’s glassy set design thoroughly purges Mando’s office of any color, artifact, or furniture that might be regarded as ethnic. Even the bookcases are vacuously neutral, populated with trophies, plaques, correspondence, business records, and binders. As the script swiftly underscores, no books. One shelf is entirely devoted to cleaning liquids, always at the ready in case a fingerprint sprouts up on a glass window or a door.

We may yearn occasionally for less polished flooring to separate us from Mando’s desk and the full-size Honduran flag that hangs vertically behind him. The frequently mopped surfaces evoke a sterile lab or an ER lobby where dirt comes to die. Or with that flag perennially in the distance, we might view that empty space as the desert that Latinx immigrants have crossed to get here. Or the spanking clean desert they found when they arrived.

Peppered with a contemptuous sneer, what Mercedes would tell you in answer to peña’s prompt is that both father and son have effortlessly become Americans without even trying. The answer Mando and Orlando would give you is grimmer than that.

By the end of the evening, thanks to peña’s deft plotting, there are battle scars supporting both points of view. The Donald’s wall across our southern border is the worst by far, but peña methodically shows us that it isn’t the only one.