Review: Ripcord at Davidson College

By Perry Tannenbaum

We’ve had more than a couple of engaging David Lindsay-Abaire moments in the Charlotte metro over the years, beginning with the Actor’s Theatre production of Fuddy Meers in 2002. Wonder of the World continued the company’s love affair with Lindsay-Abaire in 2004, and when the playwright’s Rabbit Hole took the 2006 Tony Award and the 2007 Pulitzer, Actor’s Theatre took full custody for the 2008 Charlotte premiere.

Since then, the edgy Lindsay-Abaire has largely disappeared, along with – not coincidentally, I’d contend – Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte. The exception proved the rule when Carolina Actor’s Studio Theatre mounted a fine production of L-A’s Good People in 2013, for CAST made its exit years before ATC’s demise.

Tiding us over until the current run of Ripcord in a Davidson Community Players productionat Duke Family Performance Hall, Lindsay-Abaire has graced us with numerous softer, cuddlier visitations. For he wrote the book for the musicals that brought the animated Shrek to life in a trinity of darling fluff, beginning with Shrek the Musical before hatching its twin afterbirths, Shrek Jr. and Shrek TYA. A full-length revival was staged at ImaginOn by Children’s Theatre as recently as 2022.

With the touring edition of Lindsay-Abaire’s newest Tony Award winner, Kimberly Akimbo,due for a Knight Theater rendezvous next April, many Charlotte theatergoers may rightly feel that the time is ripe for catching up with this notably successful writer. They will find a very fine production at the Duke, nestled inside the Davidson College student center, although Ripcord isn’t Lindsay-Abaire at his edgiest.

On the other hand, Ripcord isn’t nearly as humdrum as its main locale, Bristol Place Senior Living in New Jersey, would lead you to presume. That’s because roommates Abby and Marilyn have radically clashing temperaments, turning the apartment into a tinderbox. Fundamentally, Abby is misanthropic grouch who treasures her privacy – but instead of forking out the extra cash that would put her in a private apartment, she has pragmatically made herself impossible to live with.

Sunny, cheerful, and chatty, Marilyn is totally averse to the quiet and solitude Abby thrives on, breezing into the suite in a jogging outfit while her sedentary counterpart vegetates on an easy chair. She doesn’t see Abby as a mortal enemy. She’s oblivious to most of the insults that Abby hurls at her and impervious to the rest. Marilyn needs to play with others and blithely treats Abby’s hostility as playful banter.

Such insouciance totally flabbergasts and infuriates Abby, opening avenues to comedy and drama. Lindsay-Abaire slyly chooses both. So do director Matt Webster and his cast, decidedly tipping the scales toward comedy. You can easily despise both Pat Langille as the Pollyanna senior Marilyn and Karen Lico as her adversary.

Abby’s inability to dim Marilyn’s sunniness is frustrating enough for her to enlist the assistance of eager-to-please Scotty, the resident aide who cares most about the women. You can definitely empathize with Scotty when Abby confides in him and keeps pestering him to get Marilyn transferred to a single apartment that has become vacant downstairs.

Strangely enough, Scotty’s patience isn’t as boundless as the saintly Marilyn’s, which gives Lowell Lark some leverage to work with in the role. As a peacemaker, he gently informs Abby that she likes it upstairs, where it’s sunnier and there’s a nice view of the nearby park. As a dealmaker, he won’t commit to speaking to management on Abby’s behalf about moving out her roomie, but he could get in a word for her about serving up some chicken and dumplings – instead of the usual tasteless gruel – if she’ll buy a ticket and come to a show he’s acting in.

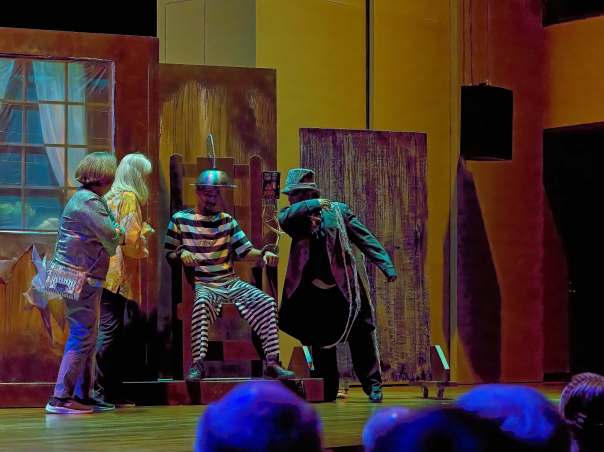

Actually, “Beelzebub’s Den” is a haunted house, liberating us from the ladies’ institutional humdrum bedroom and bath on an excursion to the first of three breakaway scenes, two of them obliging set designer Kaylin Gess to create living quarters that quickly stow away in the Duke’s commodious wings. Lots of work for the seven-person set crew. Doubling as DCP’s lighting designer, Gess gets to supply the phantasmagoria at Beelzebub’s while Beth Killion provides the outré costume designs. Technical director Shawn Halliday also gets in on the fun, here and in the signature skydiving scene.

There’s fun for us watching the haunted house antics, but Abby is neither impressed with Scotty’s acting nor scared by any of the spookiness. Abby matter-of-factly tells that she doesn’t scare. Period.

Enjoy the fun, then, but the prime takeaway from Beelzebub’s is Abby’s pride in her fearlessness. In the very next scene back at assisted living, Marilyn will insist with equal certitude that nothing Abby can do will make her angry. Resistant to all the previous bets her quirky roomie has proposed, including whether she can balance a slipper on her head, Abby sees a betting opportunity here. If Abby can make Marilyn angry, she wins. If Marilyn can scare Abby, victory!

The high stakes are predictable: if Abby wins, Marilyn leaves; if Abby loses, Marilyn gets to take over the coveted bed near the window. Game on!

And no holds barred. Lico and Langille aren’t at the high end of Lindsay-Abaire’s specified age range for their roles, so the patina of seeing ancient biddies acting like kiddies isn’t happening in Davidson. But it is definitely the playwright’s intent for Langille to exceed expectations with her imaginativeness and for Lico to shock us with her meanness and cruelty.

With stakes set this high, this is war, and the warfare escalates each time an attack fails. Bombarding your roomie with phone calls and fake messages or drugging your roomie are not out of bounds as the battles begin. Enlisting your relatives and pranking your opponents’ kin are also legit strategies as the Abby-Marilyn War escalates. The avenues of comedy and drama widen along the way.

Langille and Lico obviously revel in hatching their devilish schemes and flouting our presumptions of senior citizens’ dignity and decorum. So the Odd Couple comedy, seasoned with a half century of aging, works well. But there’s also a theme of bonding that Lindsay-Abaire plants deeply in his script from the moment his antagonists strike their bet. Reviews of the 2015 Manhattan Theatre Club premiere indicate that director David Hyde Pearce missed it with his sitcom reading, and Webster also misses some of the early hints.

Yeah, Scotty the peacemaker and dealmaker subtly evolves into the common enemy – inevitably, the uniter, if both women survive! – when Abby and Marilyn solemnly agree to keep their bet a secret from him. Lark has his best moments when he suddenly appears at an inopportune time, threatening to blow the renegade gamblers’ cover.

The deeper mojo is in the bond formed between the two combatants, a literary staple stretching past Robin Hood and Little John all the way back to the Homeric epics. We’ve all seen two boxers sincerely hugging one another after pummeling each other for 12 or even 15 rounds. That’s genuine emotion, the rawest kind, not ritual or fakery. It comes from a gradually growing appreciation of your opponents’ gifts and grit as the battle grinds on. At its keenest, the upswell of emotion also comes from the realization that your mortal enemy has pushed you to a level that you never believed possible – and that part of extra specialness of your opponents’ performance comes partly from you.

So there are many fine moments that Lico and Langille have once the game is on, though digging into them would disclose too many comical and dramatic spoilers. Equal to any one of them is the spot where, the bet having been won, the combatants begin praising each other for their devilish deeds. At that point, Webster, Lico, and Langille are all catching Lindsay-Abaire’s drift.

Supporting actors are also a treat, starting with Rigo Nova as the Zombie Butler, our host at Beelzebub’s. Transforming into Derek, Marilyn’s son-in-law, Nova is almost as surreal in his geniality and self-doubt. Victimized by one of Marilyn’s pranks, John Pace wears his victimhood well as Abby’s drifter son after donning a clown suit back at the haunted house.

Kimberly Saunders is also spectacularly silent at Beelzebub’s as the Woman in White, but her surprise appearance as Colleen, Marilyn’s daughter, is an immediate joy – for she is foiling Abby’s first wicked prank just by walking through the doorway. Soon she’ll be rubbing her hands with glee at the prospect of joining her Mom in some awesome payback. Mischief is more fun when the whole family is in on the plot.