Still in Flux, Spoleto USA Runs Brash Gamut From Barber To Balloon Pops

I first ran into Mena Mark Hanna at last year’s Spoleto Festival USA, when he was sitting near to us at Sottile Theatre, enthusiastically selling the merits of the festival to a total stranger. Almost immediately, I walked up to him and filed a complaint: my wife Sue and I couldn’t see everything! Again and again, we were forced to choose between missing the end of one performance or missing the beginning of another. Hanna, the new incoming general director at Spoleto, empathized, having faced the same dilemma.

So we were off to a good start, good enough when the calendar circled around for me to call up the Spoleto office and ask for 15 minutes of Hanna’s time after I received the green light from Queen City Nerve to write up a festival preview. To my surprise and delight, he gave me 40 and far more prime insights, experiences, and hype than I needed.

This edit of the complete interview contains all the overflow.

Perry Tannenbaum: How are you doing?

Mena Mark Hanna: Very well. Happy to have the conversation.

Yeah, this is really a treat for me too. So tell me how Spoleto is doing this year financially.

Well, knock on wood, we seem to be doing pretty well with ticket sales. And you know, we’re working to create a culture of belonging with the institution that goes into some of our accessibility efforts, like Pay What You Will and Open Stagedoor.

So I’m looking at that Pay What You Will initiative, looking into it a little bit more in terms of which events will be eligible, and it’s a pretty impressive list.

Thank you.

I was worried at first about the timing, but now I’m understanding that the timing may not have been in response to wanting to fill up houses so much as the fact that somebody, some anonymous somebody, wanted to launch this initiative.

Yeah. When you think about our society, right, we’ve got three types of institutions. We’ve got public institutions, local governmental you bodies and things like that. We also have private for-profit entities, publicly traded companies, and then we have nonprofits that kind of sit in between that public and private space.

And to me, we sort of fill in the gaps that our public sector cannot extend to our community and our private sector cannot compensate for. What that means is that we should be holders, we should be generators, we should be engendering public value for our community.

So Spoleto is not just one of the preeminent performing arts festivals. It’s also a place where people can have transformational experiences. We want to make that shared to a wider segment of our audience. We want to share to a wider segment of the public and a wider slice of the community of the Lowcountry in the greater Charleston area.

I believe very deeply in that mission. And I also think that that leads to a healthier understanding of some of the principles and values that are at the center and core of the art that we produce and create at Spoleto – principles of diversity, of access, of inclusivity. Those principles are really about engendering and creating a culture of belonging through the festival.

What art can do is that it can endow you with a new experience, an experience that you did not have before you took your seat. It can help create an understanding of another side that is normally seen by one perspective as socially disparate, as highly politicized, as a discourse that’s just way too far away. And it can break down that barrier through the magic and through the enchantment of performance.

Having those artists on stage representative of a demographic we wish to serve only takes us so far. We also have to lower the barrier of entry so that we can actually serve that demographic.

So is that a kind of a flowery way of hinting that you were in search of such an anonymous donor and pitching it in the way you were explaining it to me just now?

Well, this anonymous donor is someone whos also very passionate about these principles and about these core values at the festival. We can only do so much in order to make something like this offer to a wide range of our audience. I mean, it’s a significant amount of ticket inventory. It’s about $50,000 of ticket inventory.

Not only is that a significant amount of ticket inventory, but we have to create our own private landing page for it. There’s community outreach and initiatives that go into it. There is a whole set of staff and human resources that go into creating a program like this and running a program like this effectively. And that also takes money. So it’s not just the ticket inventory that takes money. It’s running the program.

And the hope is that we would be able to do this in a way where we would be able to offer this to our community without really losing money on it. And that’s where the generosity of this anonymous donor really shone through. And it’s someone that I think is an incredible person to be supporting the festival.

Yeah, it must be. I mean, kudos. And many thanks, I should say.

Thank you.

Is this something that even comes too late to be a part of the festival program booklet? Or is there like a special place that will be set aside for acknowledging this new program?

I don’t know if it’s going to be in the program booklet, but it’s definitely a program that we will keep up in future years.

Ah, OK! That’s through the same anonymous donor, or are you just going to carry the torch from here on in?

Well, carry the torch from here on in. I haven’t spoken with the anonymous donor about future years.

So is this like a combination of you and this donor putting your heads together and coming up with this concept or is this something that was brought fully to you, concepted by him or her?

No, no. We brought this idea to the donor.

Ah, okay. That sounds terrific. So are you feeling a certain kind of anxiety about actually coming out with a festival that has no more legacy elements in it, especially after Omar won the Pulitzer Prize?

You know, the great thing about 2022 is that it really was a collaborative effort between myself and Nigel [Redden]. And even Omar was a collaborative effort between myself and Nigel. When I came in in 2021, we had a significant production consortium of co-producers and co-commissioners for the piece.

And there were things about the piece that really needed to be addressed because the piece had sort of been in this kind of COVID stasis. So the way, you know, we think about it that even there, there was kind of a handover from Nigel to me about making sure that Omar can really work for 2022 – and that was exciting.

I mean, it’s kind of incredible to be someone who comes from Egyptian parentage, speaks Arabic, grew up sort of fascinated by opera and stage work, and spent their career in opera and was a boy soprano, to then have this opportunity to bring to life the words of an enslaved African in Charleston, South Carolina.

And those words are Arabic!

That’s a remarkable, strange serendipity for me to have been in that position of helping steward that piece to life. So it really was very much a collaborative effort in 2022. Even 2023 will have some things that are kind of holdovers from the pre-pandemic era or the canceled season of 2020. I mean, the idea of bringing Jonathon Heyward down was something that Nigel had worked on for the 2020 season as well.

So I don’t think you can point at one thing and say this is Nigel, this is Mena, this is Nigel, this is Mena. I think that there are a lot of different sorts of personalities and curators and thinkers that touch something like Spoleto Festival. It’s very, very much a collaborative entity, the way we create and curate the season.

I have expertise in music, and I have a lot of expertise in opera and maybe I have some secondary expertise in theater, but I certainly do not know enough about all of the performing arts to know every single thing so intimately wherein I would be able to curate every single chamber concert performance, every single orchestral performance, every single jazz performance.

It’s very, very, very diverse and we have a great team at the festival with our lead producer, Liz Keller-Tripp, our jazz curator, Larry Blumenfeld, our director of orchestral activities, John Kennedy, and our choral director Joe Miller. Between all of us, we curate together and try to come up with a spectacular entity that is Spoleto Festival USA.

I mean, there’s a reason why you don’t see many producing multidisciplinary festivals. They don’t really exist.

Because it’s really hard to create something like this collaboratively and source all of the right expertise in all of these different disciplines and then kind of find the right artists who could work in between those disciplines. Someone like Jamez McCorkle, for example, who’s doing A Poet’s Love this year, which is wonderful.

It’s a difficult, strange operation. It’s different from an opera company, a dance company, a theater, so on and so forth. It’s all of these things combined, and then it’s sort of event-oriented and time-delimited. So to bring these things together, it’s really about, you know, all of this being greater than the sum of its parts and that’s due to some great expertise that we have at the festival.

Yeah. I have two questions about the formatting of the festival. One is whether the clearly discernible thematic structure of last year’s festival, bringing the East or Middle East to the West, has been repeated in any way that I have not been able to so far discern in this year’s festival. And second, whether the position that Geoff Nuttall held is just being kept vacant for this one festival or whether he’ll be replaced by next year?

So let me tackle the first question first. I am not a fan of really obvious themes that kind of are pedantic and hit you over the head. Last year was a unique case insofar as it was the first festival coming out of the pandemic, and there was a lot in that festival that also addressed some of the concerns that were raised in the pandemic that have to do with our own societal dissensus and our own inability to reckon with our past culturally, historically, politically as a country.

And Omar is a part of that, but it was only a part of that. It was maybe the centerpiece of that, but a lot of that just kind of overflowed outside of Omar. The idea of centering Africa as also an origin point of the United States is something that will always be a particular concern of the Spoleto Festival because we’re in Charleston. And Charleston was the port of entry for the Middle Passage.

Charleston has at its core an incredibly rich Gullah-Geechee-West African-American tradition that is part of the reason this is such a special, beautiful place to live in with its baleful history. So I think that you see that this year, you see that with Kiki [Gakire] Katese and The Book of Life, you see that with Dada Masilo and the Sacrifice, you see that with Abdullah Ibrahim and Ekaya.

You see that these are also artists from Africa that are engaging in their own social, cultural and political discourses. That Kiki is engaging with how a country tries to reconcile with its recent, terrifically horrific past of the Rwandan genocide as someone who grew up Rwandan in exile. You see that in the work of Abdallah Ibrahim, who was really one of the great musicians of the anti-apartheid movement, who composed an anthem for the anti-apartheid movement, was in a kind of exile between Europe and North America in the 80s.

Then when he finally came back to South Africa for Nelson Mandela’s inauguration, Nelson Mandela called him our Mozart, South Africa’s Mozart. So you see that with these artists, how they are engaged in their own social, cultural and political discourse, and how they are trying to reckon with their own past. And that’s something that is an important lesson that we want to take on and learn in a place like Charleston.

We can look to African artists and understand that they are also part of this place and that they are also part of America’s origin story. It’s not just about Europe and North America. So I think that’s always going to be something that’s on prominent display at the festival.

But even more so than that, this is a festival that, if you look at a kind of undercurrent thematically, there is unity there. I always want the festival to kind of have a cohesiveness, a cogency, without necessarily saying, “This year we are talking about crime and punishment,” or “this year we are talking about love’s labour’s lost” or something like that.

No, I want there to be a kind of cohesiveness without necessarily us being able to see what the theme is. That’s what is kind of exciting and unifying about putting all of these different pieces together. If there is something that unifies a lot of these pieces, it’s about us understanding that we are telling stories from our past, some of them the most ancient stories that we have in our intellectual heritage. We are looking at these stories with a different sense that takes on the reverberations of today’s social discourse.

I mean, An Iliad going back to the Trojan War is as much about war and plague then as it can be today with the reverberations of Ukraine and the pandemic. Vanessa, which is an opera that was premiered in 1958 and then brought back to the festival in 1978, is reinterpreted here through the lens of a remarkable female director, Rodula Gaitanou. And there is a quite strange ambiguous moment in the opera of either an abortion or a miscarriage.

What does that mean now when we are looking at a renewed political assault on female autonomy? So these stories take on new messaging, new reverberation in 2023. And we need to retell these stories with the new lens of today.

You look through all of these pieces, The Crucible, The Rite of Spring, Vanessa, An Iliad, even Dichterliebe by Schumann, and it’s all about taking those stories and kind of having a renewed understanding of how we tell those stories and who we are telling them to, and who is telling those stories.

About the second point, chamber music. Yeah, I think all in due time, there will be new leadership in the chamber music series. I mean, Geoff was this remarkable figure who, speaking of storytelling, was perhaps one of the most incredible practitioners of his practice insofar as making chamber music accessible and having us sort of like look at Brahms, Beethoven, and Haydn – maybe not Brahms, he didn’t like Brahms very much – with a renewed sense of understanding, and he did that by sort of giving the story of chamber music in America a completely new life and a new understanding.

I became really close to Geoff over the last two years. He was actually on the hiring committee for me, and he was one of two people that would report to me on the hiring committee, and it was a committee of ten people. I largely took this position because Jeff convinced me to. He convinced me to because he was so excited about what we could invent, what we could create together.

He was so excited by the interdisciplinary-ness of the festival and how that could actually spill over into chamber music. We at least got one festival together. We started to make changes.

At least we had one festival together, but it’s tough, man. This has been a really, really tough year without Geoff. It’s been a year of enormous highs and lows. It’s been a year where the festival won, helped to produce and create an opera that did win the Pulitzer and a year where it lost its lodestar in Geoff.

It’s been a very, very, very difficult year. We are making sure that we are celebrating Geoff through the festival. The festival opens with a celebration of all the music that he loved and in the grandest statement possible at the Gaillard with orchestra and chamber music members and so on and so forth and different soloists.

Then all through the chamber music series, it’s going to be a celebration of Geoff through the people who loved him the most, his chamber music family. People that you know: Paul Wiancko, Pedja Muzijevic, Livia Sohn, Alisa Weilerstein, Anthony Roth Costanzo. That was his family. They will all have an opportunity – of course, also the St. Lawrence String Quartet will be here – they will all have an opportunity to celebrate him and live and love what Geoff was so great at by performing and playing together.

So will there be chamber music at the festival in the future? Of course. The music will continue to rock at the Dock.

I was more specifically interested in who will replace Geoff in his hosting chores, and I guess attached to that question, whether or not it might be time to step back and ask yourself if there isn’t a lot of room for improving the diversity of the people who are in charge of the various music departments at Spoleto, who seem to be conspicuously white and male, and remembering that Nigel stepped down because he felt he was part of that pattern.

Yeah, at the very least, I’m Arab. No, I think Perry, you’re 100% right. To me, the important thing is that we don’t put someone in a place out of a sense of performative duty. We put someone in that place because they are going to be of great accretionary value to the festival, because they espouse the ideals of the festival, and because they are the best person to be in that position.

I’m the first to say that I would balk at any kind of jingoistic declaration that I’m in such and such position because I’m an Arab American. I think people of color want to be recognized for the work that they do and often, the structural sort of biases that they have to overcome in these imperfect institutions in order to get to those positions.

To me, it’s about the best person, and of course, making sure that we look extra hard to find some of those people that may have been swept under the rug by these implicit biases that exist in our imperfect institutions. We’re definitely going to take a keen look at chamber music over the next few years. Well, actually, through this festival, let me say, and into the summer.

And yeah, there will be some structure that will replace Geoff. Additionally, it’s important to mention that this year, we did not want to put someone in place immediately to replace Geoff. We didn’t think that was appropriate.

We wanted to make sure that this was a celebration of Geoff, and that the people who were celebrating him and honoring him were doing so by performing at the Chamber Music Series, helping to co-curate the Chamber Music Series, and helping to emcee the Chamber Music Series. This year, we decided to make that a collective effort in his honor.

But if there is a template in the Chamber Music Series about who does host, until now, 2023, the hosts have all been people who occasionally perform on the Dock Street stage. So do you feel locked into that?

Oh yeah, I don’t think we’ll peel that back. No, no, no, no, no. Because I think one of the important things is actually the ability to host Chamber Music and make it feel approachable and intimate. That should come from a practitioner of Chamber Music, someone who could actually perform it on stage.

Yeah, bravo. I was hoping I wasn’t misinterpreting what you were saying. Like you could have done a nationwide search for somebody else.

No, no. Thank you for the clarifying question. There’s no way we’re going to hire John Malkovich to host Chamber Music. That’s not the vibe.

And the great thing about Geoff is that he was able to demonstrate the pieces effectively as such a great performer. And that’s what made that Chamber Music Series, and that’s also true of Charles Wadsworth, and that’s also true of Leonard Bernstein. That’s what makes the great communicators in classical music great, is that they can sit there, they can communicate it, they can perform it, and they can do so without any compunction or any sense of superiority.

For sure, the people who will be hosting Chamber Music this year and into the future will be practitioners of Chamber Music and people who are playing in the Chamber Music Series.

Hooray. So what do you think, or is it dangerous to say what you think the highlights of Spoleto 2023 are?

Well if you allow me a kind of punchy suggestion as a general director, which is very carefully branded and thought through, my suggestion for a first-time participant would be to see two things you like and feel comfortable about seeing, maybe that’s Nickel Creek and Kishi Bashi, and two things that are really pushing the envelope for you. So maybe that’s Dada Masilo and Only an Octave Apart.

Personally, I’m extremely excited about A Poet’s Love, which is a world premiere project we’re doing with Jamez McCorkle, who was Omar in Omar last year. And it’s partly exciting because you have the sheer unadulterated joy of seeing this piece be performed by a single accompanist and vocalist.

You know, I’m a pianist by background and trade, and I’ve accompanied Dichterliebe before, and it’s enormously difficult to perform. And the fact that Jamez can just kind of do it in one essence – it’s just like music incarnate. It’s totally, totally insane that he can do that. I mean, he’s one of the most spectacular artists that I’ve ever come across.

He’s doing it with collaboration with Miwa Matreyek, who does this kind of like shadow puppetry, moving image art that’s kind of like in a gothic whimsy that feels very appropriately 19th century, but also with this kind of magical technology through projection and shadow work. So it’s a really cool, strange project and I assure you that you will never have seen anything like it before.

I’m also extremely excited about this production of Vanessa. I mean, the cast is just killer.

You have Nicole Heaston as the lead with Zoie Reams and Edward Graves and Malcolm MacKenzie and Rosalind Plowright. I mean, that is just a world class cast at the very, very top. And it’s also really cool to see these roles, which are traditionally sung by Caucasian people, being sung by people of color. I think that’s also an incredible sort of sense of joy and interpretation in this piece. And it’s conducted with absolute precision and aplomb by Tim Myers. So I’m excited about that.

I’m very excited about Only an Octave Apart. You could only have seen it publicly in either New York or London. So to have it here, it shows sort of how prominent Spoleto is on the world stage – that even if we’re not producing something and we’re presenting something, most of the time, if you’re going to see something here, it’s going to be very, very difficult for you to see it at a local theater or in a place other than New York or London.

So it’s cool to see that. I’m extremely excited about Scottish Ballet and The Crucible. I mean, that’s a new score by a composer named, believe it or not, Peter Salem.

That is unbelievable. I’ll give you that.

It is hard for me to say: I’m also excited about Kishi Bashi. That’s something you’re going to start seeing a little bit more in the festival on the popular music side, an expansion of what we normally do in our genres. We want to try to find these artists that are like pivot artists that occupy these interstitial spaces between dance and theater and classical music and jazz and folk music. And Kishi Bashi is one of those.

He plays the violin on stage. He has all of these violinists on stage with him, but it’s this kind of strange, hallucinatory, intoxicating music that’s like somehow trance music and Japanese folk music, but using sort of Western classical instruments. But it’s very much in an indie rock tradition as well.

And to kind of see us expand and experiment a little bit more and try to widen the tent of what the festival does is exciting in 2023. And you’re going to see a little bit more of that in ‘24, ‘25, and ‘26.

That’s definitely promising. Are we also experiencing or witnessing at Spoleto something of a reconciliation with Gian Carlo Menotti beginning?

Hooo!

You didn’t expect that one, did you?

I did not expect that one. All I can say about Gian Carlo is that he had great vision in founding the Spoleto Festival and was a spectacular impresario. I never knew him personally. And you know, if you’re talking about a reconciliation or reckoning artistically, I’m very happy to speak about that, because I think that Vanessa is a work that was premiered in 1958 at the Met, it won a Pulitzer that year, it was then done in Spoleto in 1978. I think Barber lived until 1991.

So that moment when Vanessa was done in 1978 was not just a moment for the festival. Because it was a Great Performances capture that was syndicated throughout the country on PBS. It was a great moment of national recognition for the festival. But it was a great moment of re-evaluating Samuel Barber as a composer nationally.

And it was really when people started to look at Samuel Barber. You know, in 1978 there was a great decade-and-a-half of serious intellectual academic ultra-serialism in classical music, the likes of not just Boulez but on the American side with Milton Babbitt and so on. The work of Samuel Barber in his kind of neo-romantic lyricism had fallen out of fashion and out of favor by the late ‘70s, especially also with the rise of the minimalism movement with the likes of Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass and now John Adams.

So it’s really a moment of recognizing Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti in the creation of this work of Vanessa, and I think that Vanessa is a great American opera that has truly been underappreciated. It tells a story that is urgent, is psychologically harrowing, is about reclusion in a way, which is very appropriate after the pandemic, perhaps kind of scarily so. It tells a story about love and about the blurriness and ambiguity that can happen in love.

It’s a harrowing kind of weird story that is told on stage, especially in this setting, through a very Ingmar Bergman-like production that has such spectacular force perception, such great theatrical ambiguity onstage, such depth where you can sort of see through one wall, see through past another wall, and then see through a third wall, and you have this sense that the stage is never ending. It’s just a sense of false prosceniums.

I think if we’re going to reevaluate Gian Carlo Menotti, let’s do so from an artistic perspective and look at what he had given to us, not just as a great impresario, but as a librettist and as a director, as well as a composer, but as a librettist and a director through the work of Vanessa by Samuel Barber.

Yeah, I think it might be overdue for us all being reminded just how talented he was as a writer.

Yeah, I agree. And also how important he was for opera in North America. I mean we have not just one of the great festivals in this country due to him. We have one of the great producing opera festivals in this country due to him. He was a key figure not just as an impresario, but as a composer and a librettist and a director working in American opera and creating a voice for American opera on both sides of the Atlantic.

So yes, I think that’s correct.

In terms of being underappreciated, I would look at Spoleto itself in addition to Barber from the standpoint of becoming maybe the most important force for new music that we have right now.

I don’t know if we can say we’re underappreciated. I mean, we put on Omar, and it’s going all over the place, and we’ve certainly received recognition through the incredible work of Rhiannon [Giddens] and Michael [Abels] and their work being recognized for a Pulitzer. But I think the festival has always been recognized as a great center for new music and new opera specifically.

Especially in the last five, 10 years, you’ve seen some works, Quartett by Luca Francesconi and Das Mädchen [The Little Match Girl] by [Helmut] Lachenmann, and Tree of Codes by Liza Lim, which were either North American premieres or world premieres. And in those cases, you see a real sense that there’s an internationalism to the festival, that the festival is promoting work that is truly importing from Italy, Germany, Australia, and so on, putting it on here and doing so at the highest sort of caliber of creative excellence.

But I also think that the festival is about creating new work and creating new American work. And that was something that you see more in the Menotti years in the ‘70s and ‘80s, where this is the center of new American opera and new American work.

That’s something that we’re going to be looking at over the next few years: How can Spoleto be a sandbox of creative ingenuity, not just in opera, but across multiple disciplines? How can it be an incubator, an accelerator of new ideas when we are in a city with a tragic past and an incredible outward beauty? What does that mean for the creation of work here and how that work can potentially have national and international reverberations?

So I think that this is a center of new work, generally speaking, and it’s really going to lean into that over the next few years.

Great to hear it.

Thank you, Perry.

And marvelous to talk with you.

I can’t believe it’s taken us so long.

Recognition of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement and the We See You White American Theatre manifesto (issued by a coalition of BIPOC artists in 2020) were certainly on Nigel Redden’s mind when he decided that the 2021 Spoleto Festival USA would be his last as general director. White and long-tenured at the Charleston arts fest, Redden saw himself personifying what needed to be changed, not merely in American theatre but across the nation’s arts.

Yet that wasn’t to say that Spoleto was backward in infusing diversity into its programming or in embracing contemporary, cutting-edge work in its presentations of music, theatre, and dance – which made Redden’s swan song, at a Festival that constricted and hamstrung by Covid-19, all the more poignant. But all Redden’s work was not truly done, even after he officially stepped down last October, for there was one grand project of his that had yet to be completed. Spoleto’s commission of Omar, the much-anticipated new opera by Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels would at last be unveiled after being shelved for two years.

Based on the slim autobiography of Omar Ibn Said, the only known narrative by an American slave written in Arabic, Giddens’ new work was appropriately co-commissioned by the University of North Carolina, for Omar’s servitude began in Charleston before he escaped to a more benign slaveholder up in Fayetteville, NC. Rather than letting this world premiere stand as an isolated testament to Redden’s legacy – or a belated rebuke targeting the infamous Muslim ban of 2017 – incoming general director Mena Mark Hanna has emphatically made Omar the tone-setting centerpiece of his first Spoleto.

Predictably enough, Giddens and Abels sat for a public interview with Martha Teichner on the afternoon following the premiere, just a few hours before she and her husband, Francesco Turrissi, appeared in an outdoor concert at Cistern Yard. Five days after the world premiere at Sottile Theatre, the principal singers from Omar and the choir resurfaced at Charleston Gaillard Center for a “Lift Every Voice” concert, further affirming Black Lives. But that theme, as well as Ibn Said’s African origins and Islamic faith, suffused the Festival’s programming more deeply than that.

In the jazz sector, for example, two African artists were featured with their ensembles at the Cistern on successive night after Giddens’ concert, Senegalese singer Youssou N’Dour and his orchestra followed by South African pianist Nduduzo Makhatini and his quartet. More importantly, saxophonist Ravi Coltrane, three years after participating in a Geri Allen tribute, paid homage to his distinguished mom, harpist/organist/composer Alice Coltrane and her 1971 Universal Consciousness album, a spiritual landmark that defined Indocentric jazz, laced with flavorings of Africa, India, Egypt, and the Holy Land.

Unholy Wars was another Spoleto commission, with tenor Karim Sulayman as its lead creator, furthering the pro-Muslim thrust of the Festival’s opera lineup. Taking up Claudio Monteverdi’s Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, the 1624 opera that extracted its tragic love story from Torquato Tasso’s epic Jerusalem Delivered, Sulayman boldly flipped the First Crusade narrative. Sulayman, a first-generation American born in Chicago to Lebanese immigrants, conceived a counter-Crusade, attempting to render vocal compositions by Monteverdi, Handel, and others through the perspective of those defamed and marginalized by the prevailing white Western narrative.

Portraying the narrator, Sulayman chiefly championed the warrior woman Clorinda – who needed to be white-skinned and convert to Christianity for 17th century Europe to see her as worthy of Tancredi, the valiant Christian knight who mistakenly slayed his beloved in combat. Soprano Raha Mirzadegan as Clorinda outshone bass baritone John Taylor Ward’s portrayal of Tancredi, while dancer Coral Dolphin, devising her moves with choreographer Ebony Williams, upstaged them both. We could conclude, in stage director Kevin Newberry’s scheme of things, that Dolphin’s dancing silently represented the Black beauty that Clorinda was never allowed to be.

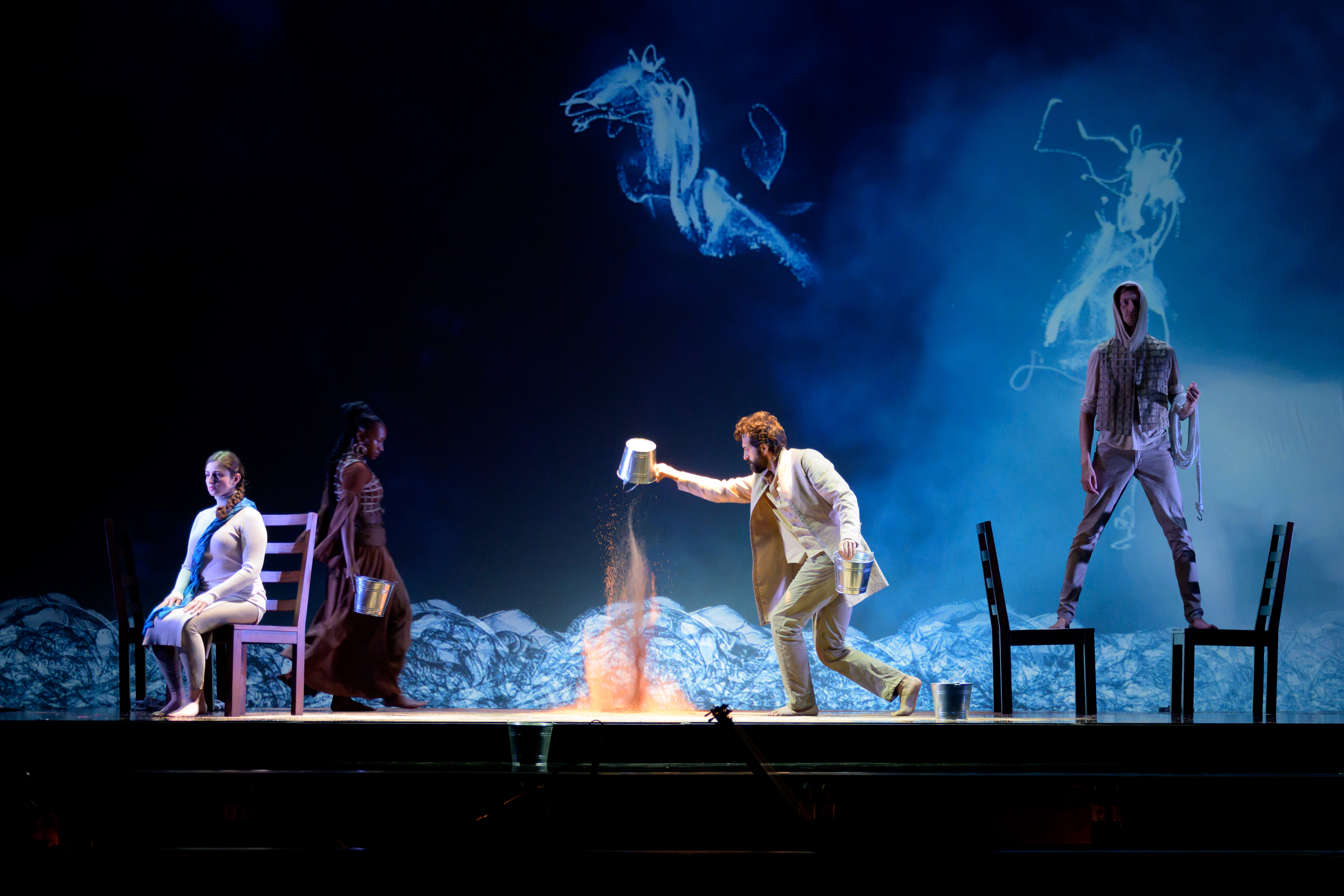

Known for directing such cutting-edge operas as Doubt, Fellow Travelers, and The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, Newberry had no qualms about creating huge disconnects between his actors’ actions and the Italian they sang. Costume designer David C. Woolard was similarly liberated in attiring them, evoking Lawrence of Arabia more readily than Richard the Lion-Hearted. Water, sand, heavy rope, and four simple chairs supplanted onstage scenery at Dock Stage Theater, but Michael Commendatore’s steady stream of animated projection designs, coupled with the production’s supertitles, more than compensated for the sparseness onstage, keeping us awash in sensory overload. If you tried to keep pace with the supertitles on high, sometimes barely legible, you could easily be distracted from the action below.

Consulting your program booklet to determine what was being sung by which composer would only have compounded your confusion. Best to listen, look, and enjoy. For if this sensory-rich spectacle – laden with mysterious sand and water ceremony – strayed far from fulfilling Sulayman’s intentions, the music, the voices, and the dance yielded constant pleasure, wonder, and delight.

More touted and deliciously marketable, Giddens’ Omar proved to be more treasurable and on-task, providing tenor Jamez McCorkle with a career-making opportunity in the title role. Directing this stunning world premiere, director Kaneza Schall is laser-focused on the most pivotal event in Said’s life in America when, imprisoned in Fayetteville, he is released from jail and purchased by a benign master because of he has – miraculously, in the eyes of local yokels – written in Arabic script on the walls of his cell.

Written and printed language, from the floor upwards to the Sottile’s fly loft, is everywhere in Schall’s concept: dominant in Amy Rubin’s set, Joshua Higgason’s video, even permeating the costumes by April Hickman and Micheline Russell-Brown. If you ever believed the libelous presumption that Africans were all brought to America bereft of any literacy, maintained in their pristine backwardness by their benevolent masters, Schall’s vision of Omar was here to brashly disabuse you.

And if you were under the impression that Africans came ashore in Charleston without any coherent Abrahamic religion, their poor souls yearning to be redeemed by the beneficence of Christianity, Giddens labored lovingly to enlighten you, the beauty and spirituality of her score enhanced by Abels’ deft orchestrations. As a librettist, Giddens could have benefited from some discreet assistance – and the challenge of scoring somebody else’s text. Melodious and religious as it is, Omar could stand to be a more dramatic opera, and as a librettist, Giddens could have usefully been more detailed.

Stressing Said’s spirituality, Giddens neglects his intellect, never referencing the range of his studies or the full spectrum of his manuscripts. Nor is there a full fleshing-out of why Said was imprisoned in Fayetteville or how it could be that Major General James Owen could take him home without returning the fugitive slave to his previous master, described in The Autobiography as “a small, weak, and wicked man, called Johnson, a complete infidel, who had no fear of God at all.”

The embellishments that Giddens gives us are all gorgeous. Owen’s daughter, Eliza, has a beautiful aria sung by Rebecca Jo Loeb, entreating her dignified dad to see the providence in Omar’s coming to their city. Further mentoring our hero, soprano Laquita Mitchell was Julie, a fellow slave in Fayetteville who will vividly remember her previous meeting with Omar at a Charleston slave auction. More majestically, mezzo-soprano Cheryse McLeod Lewis is a recurring presence as Omar’s mother, Fatima. Long after she is slain by the marauders who enslave Omar, she comes back to her son in a dream, warning him that Johnson is fast approaching to murder him. Mitchell and Lewis subsequently team up to urge Omar to write his story, a summit meeting with McCorkle that is the clear musical – and emotional – high point of the evening.

Plum roles also go to baritone Malcolm MacKenzie, who gets to sing both of Omar’s masters, the cruel and godless Johnson before intermission and the benign, bible-toting Owen afterwards. The question of whether Said sincerely converts from Islam to Christianity is pointedly left open. Notwithstanding his utter triumph, we probably have not seen the full magnificence that McCorkle can bring to Omar, for he was hobbled in the opening performances, wearing a therapeutic boot over his left ankle that I, for one, didn’t notice until he resurfaced as the highlight of the “Lift Every Voice” concert, bringing down the house with a powerful “His Eye is on the Sparrow.”

Scanning the remainder of Spoleto’s classical offerings, I’m tempted to linger in the operatic realm, for Yuval Sharon’s upside-down reimagining of La bohème at Gaillard Center, despite its time-saving cuts to Act 2, completely overcame my misgivings about seeing Puccini’s four acts staged in reverse order. Yet there were more flooring innovations, debuts, and premieres elsewhere.

Program III of the chamber music series epitomized how the lunchtime concerts have evolved at Dock Street Theater under violinist and host Geoff Nuttall’s stewardship. Baritone saxophonist Steven Banks brought a composition of his, “As I Am,” for his debut, a winsome duet with pianist Pedja Muzijevic. Renowned composer Osvaldo Golijov, a longtime collaborator with Nuttall’s St. Lawrence Quartet, was on hand to introduce his Ever Yours octet, which neatly followed a performance of the work that inspired him, Franz Joseph Haydn’s String Quartet, op. 76 no. 2.

Upstaging all of these guys was the smashing debut of recorder virtuoso Tabea Debus, playing three different instruments – often two simultaneously – on German composer Moritz Eggert’s Auẞer Atem for three recorders and one player. Equally outré and modernistic, More or Less for pre-recorded and live violin was a new composition by Mark Applebaum, customized for Livia Sohn (Nuttall’s spouse) while she was recuperating from a hand injury that only allowed her to play with two fingers on her left hand. If it weren’t bizarre enough to see Sohn on the Dock Street stage facing a mounted bookshelf speaker, the prankish Applebaum was on hand to drape the speaker in a loud yellow wig after the performance was done.

On the orchestral front, two works at different concerts wowed me. Capping a program at Gaillard which had featured works by György Ligeti and Edmund Thornton Jenkins, John Kennedy conducted Aiōn, an extraordinary three-movement work by Icelandic composer Anna Thorvaldsdottir. Hatching a soundworld that could be massively placid, deafeningly chaotic, weirdly unearthly, or awesome with oceanic majesty, Aiōn decisively quashed my urge to slip away to The Cistern for Coltrane and his luminous harpist, Brandee Younger. We were forced to arrive a full 30 minutes after that religious rite began.

My final event before saying goodbye to Spoleto 2022 treated me to sights I’d never seen before. On an all-Tyshawn Sorey program, Sorey ascended to the podium at Sottile Theatre and took us all to a pioneering borderland between composition and improvisation that he titled Autoschiadisms. Instead of a baton, Sorey brandished a sharpie beating time, sheets of typing paper with written prompts, or simply his bare hands making signals. Sometimes Sorey simply allowed the Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra (splendid as usual) to run on autopilot while he huddled over his score, writing new prompts with his sharpie on blank pages before holding them high.

And the music was as wonderful as it was exciting, clearly an advance upon the other compositions on the bill, For Roscoe Mitchell and For Marcos Balter, conducted respectively by Kennedy and Kellen Gray. In the surreal aftermath of his triumphant premiere, Sorey had reason to linger onstage during a good chunk of the intermission. Musicians from the Orchestra swarmed him, waiting patiently for Sorey to autograph the sheets of paper that the composer had just used to lead them. The ink was barely dry where the MacArthur Genius of 2017 was obliged to write some more.

For the past two years at Spoleto Festival USA, opera has been the bellwether of how this massive festiv

al of the performing arts – including theatre, jazz, dance, symphonic and chamber music – has been changing and evolving. In 2015, opera programming untethered itself from its customary balance of new works with outré offerings from recognized masters. The tandem of Paradise Interrupted in its world premiere and Veremonda in its American debut underscored the transformation of Spoleto into the world’s leading showcase for new and/or different classical music.

Last year, what seemed like a move toward more populist programming, with Porgy and Bess as the marquee opera and an increased presence of American jazz artists, did not affect a continuing drift toward more modernist music. What the Porgy and Bess celebration of the festival’s 40th season really signaled was that, with the radical facelift to the reopened Gaillard Center, truly grand productions of grand operas were now possible in Charleston, SC.

Even before the Gaillard closed down for its makeover after the 2012 season, it was clear that, from a technical standpoint, only lackluster stagings could be expected there. Gustave Charpentier’s Louise had been the last operatic attempt in 2009. During the renovations, you could be charmed by Spoleto’s productions of Kát’a Kabanová and Le Villi at Sottile Theatre, but you could hardly pretend they were on a grand scale.

With this year’s presentation of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, grand lyric opera was emphatically enthroned at the festival, although I suspect there were budgetary constraints in the wake of last year’s anniversary extravagances. Now that might not explain why there was no bed, no window, and no writing desk – all mentioned in the libretto – for Tatyana’s famed letter scene. Why would stage director Chen Shi-Zheng’s austerity extend to depriving the poor woman of pen and paper until after she has finished writing?

Suspicions came unbidden when, after a snowbound video of a Russian forest ran over the overture, spindly trunks of wintry trees descended from the fly lofts and haunted nearly the entire production. The concept didn’t jibe with arrival of the family estate’s peasants heralding their completion of the harvest. More puzzling, the lovely trees were whisked to the wings prior to the scene where they might make the most sense, the duel between Onegin and the hotheaded poet Lensky.

Projections that replaced the trees for the duel and for the ultimate denouement, where he receives his richly deserved rejection from Tatyana, were actually darkly effective. But the best use of set designer Christopher Barreca’s trees came when, half-lifted into the flies and colorfully illuminated, they simulated chandeliers at the regal ball in Prince Gremin’s palace, where Onegin is thunderstruck by the transformation of Tatyana into a poised and polished aristocrat.

Whatever toll austerity might have taken on the scenery, it was not a factor in the singing. Taxed with delivering the letter scene with no props except a chair (those lingering tree trunks did fill up momentarily with projections of Tatyana’s handwriting), soprano Natalia Pavolova glowed with youthful longing in her American debut. She was hardly less impressive as a mature princess, bearing herself imperially in the ballroom, and her creamy voice thickened pleasingly with emotion in the final tête-à-tête with Onegin. Lacking the hauteur I saw from Dmitri Hvorostovsky when I saw him in the role opposite Renee Fleming, baritone Franco Pomponi was less of a cold-hearted jerk when Onegin rejected Tatyana and killed Lensky – and more pitiable when he comprehended his mistakes.

Solid as he was vocally, Pomponi was thoroughly upstaged by tenor Jamez McCorkle as Lensky. The pride and pathos that McCorkle brought to Lensky’s final pre-duel meditations were shattering. Nearly as touching – and as vocally powerful – baritone Peter Volpe’s weighty, twilit confessions to Onegin as Prince Gremin were the perfect prelude to the cad’s comeuppance.

Acoustics at the new 1,800-seat facility helped to keep the front-liners relaxed, unless they had the misfortune of singing from the rear half of the stage, which introduced a noticeable echo effect. Clarity and presence improve markedly for the Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra when it ascends from the pit to the stage, where it is wrapped in a tall, wood-grained shell and covered by a sloped and sculpted acoustic ceiling.

With the addition of the Westminster Choir conducted by Joe Miller, the worthy heir to Joseph Flummerfelt, orchestral concerts have also grown grander in recent years. Ramping up to the return of the Gaillard, Miller and the Westminsters presented the St. Matthew Passion at the Sottile in 2015 before helping to break in the new hall last year with Beethoven’s Mass in C and his Choral Fantasy. Once again mixing the sacred with the secular at the Gaillard, Miller programmed Mozart’s unfinished “Great” Mass in C Minor, preceded by two Ralph Vaughan Williams settings, one for Psalm 90 (“Lord, Thou Hast Been Our Refuge” and the other from the moonlit Act 5 love scene that punctuates the hurly-burly of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice (“Serenade to Music”).

Augmented by the Charleston Symphony Orchestra, the Westminster Choir sounded massive and sure, and the Festival Orchestra, culled from advanced conservatory students and young professionals through nationwide auditions, still strikes me as the best American orchestra of its kind. The bigger sound of the choir made the “Lord, Thou Hast Been Our Refuge” more soothing and cosmic, building to a majestic finish. An exquisite dialogue between orchestra and vocalists followed in the Shakespeare setting, as six of the Westminster choristers then came downstage and formed a mini-choir, joining the four guest artists who would sing in the Mozart.

It was gratifying to see McCorkle again after his fine Lensky, but once again, he didn’t draw a leading role in the Mass after shining briefly in the “Serenade.” Mozart began this liturgical piece as a showcase for his wife, Constanza, and soprano Sherezade Panthaki shone in much of the coloratura spotlight that he managed to finish, especially when powering the climax of the Credo. Soprano Clara Rottsolk ably complemented Panthaki in the Gloria, and bass André Courville rounded out the quartet of soloists in the concluding Benedictus.

Of course, there was nothing miniscule about the other orchestral concert, beginning with Anna Thorvaldsdottir’s icily atmospheric Dreaming and climaxing with Mahler’s Symphony No. 4. Following up brilliantly on her lustrous 2013 debut in the title role of Matsukaze, soprano Pureum Jo filled the folksy jollity of the Sehr behaglich (“Very comfortable”) finale with a heavenly purity.

Yet I found myself even more encouraged and excited by what’s happening in the chamber music sector of the festival. For the first time since taking over the reins of the daily chamber music series in 2010, violinist Geoff Nuttall had to acknowledge the absence of his mentor and predecessor, Charles Wadsworth, on the mend up in New York. As host and programmer of the lunchtime Dock Street Theatre concerts, Nuttall has come into his own, greatly increasing the amount of modern and contemporary music that is played while chipping away at the barrier that previously distinguished the genial, comical, and witty introductions to the music from the formality of the performances that followed.

There’s likely a connection between the two developments. When a percussionist provides the entire audience with pairs of rocks to bang together during a performance of new music, or a composer triggers video and sound cues with an iPhone, formality begins to break down. The effect spread to more antique music when countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo called attention to the kinship between a Vivaldi aria and Elvis Presley’s “Don’t Be Cruel.”

Performances have sprouted a jocular dimension here and there, thanks to the deployment of clarinetist Todd Palmer as comedian-in-chief. After Nuttall spoke vividly of Giovanni Bottesini’s virtuosic displays on double bass during operas that he conducted in the mid-1800’s, appearing mid-performance to dazzle with improvised fantasias on tunes from that evening’s opera, Palmer joined double bassist Anthony Manzo and pianist Gilles Vonsattel in Bottesini’s Duetto for Clarinet and Double Bass with Piano. Between two of the fantasias, Palmer did a riff of his own on the diva aspects of the spoken intro, flashing some leg and modeling a sock that was more flamboyant than any I’ve seen on even Nuttall’s feet.

There was more later as Nuttall and his St. Lawrence String Quartet joined Manzo, flutist Tara Helen O’Connor, and pianist Pedja Muzijevic in a cunning reduction of Symphony No. 100 by Haydn, our host’s favorite composer. As Nuttall explained how this “Military” Symphony came by its nickname, you had to wonder where the hellish percussive roar would come from when the second movement started. The answer came during the interval between the opening Adagio-Allegro and the signature Allegretto: emerging from the wings, Palmer marched onstage – literally marched, mind you – harnessed into a big bass marching drum and brandishing two mallets.

It was actually a military parade, since cellist Joshua Roman with a pair of cymbals and violinist Benjamin Bellman with a wee triangle marched in right behind Palmer. Earlier in the concert, right after the Bottesini, these two accomplices had given an absolutely delicious account of Ravel’s Sonata for Violin and Cello. If anything, the exit after Haydn’s second movement, led again by Palmer, was even more ceremonial. Yet there were more surprises to come. Violinist Daniel Phillips (flutist O’Connor’s husband) heralded the opening passages of the Presto finale from the balcony, and Palmer’s percussion trio resurfaced at the rear of the hall to pound, clang, and clink the final measures.

Musically, Palmer’s shining moments came three programs earlier when he played the Beethoven Clarinet Trio with Muzijevic and Roman, while the best of Nuttall came when he led an inspired performance of the Mendelssohn Octet. Some of the inspiration no doubt came from the meet-up between Nuttall’s St. Lawrence Quartet and his newest Spoleto recruits, the Rolston String Quartet. They won the Banff International String Quartet Competition 24 years after the elder Canadian quartet won the same prize in 1992. There were moments when Rolston cellist Jonathan Lo and violist Hezekiah Leung gazed upon Nuttall’s rapt antics – his back-and-forth swaying on the first chair and his spasmodic knee-lifts – with undisguised, wide-eyed wonder, apparently unaware that he played with the same abandon, eccentricity, and charisma when he first came to Spoleto in 1995. Except that his hair was longer then.

Effects of Nuttall’s stewardship now extend beyond the Dock Street Theatre. Two of the chamber music pianists had concerts booked at other venues. Muzijevic, who also traveled to Hamburg to select the new Steinway for the Dock Street series, fashioned a set of “Haydn Dialogues” at the Simons Center Recital Hall – four Papa pieces interspersed with works by Jonathan Berger, Morton Feldman, and (with an alternate prepared piano) John Cage. Stephen Prutsman put on his composing hat at Woolfe Street Playhouse, plucking a string quartet from the Festival Orchestra to score three silent films, “Suspense,” “The Cameraman’s Revenge,” and “Mighty Like a Moose.”

For the past two years, Nuttall has performed at Gaillard Center in chamber music segments of Spoleto Celebration Concerts, further extending his presence. He and his spouse, violinist spouse Livia Sohn formed half of a quartet, including Muzijevic and St. Lawrence cellist Christopher Costanza, in a reduced adaptation from Vivaldi’s L’estro armonico concertos. Until 2013, when oboist James Austin Smith joined his chamber music stable, Nuttall was no more likely to program Vivaldi’s music than Wadsworth was, let alone play it.

What really brought Vivaldi to centerstage at Spoleto was the sensation that countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo created last season in his first three programs at Dock Street. Costanzo didn’t sing Vivaldi then, ranging instead from Handel to Gershwin to Osvaldo Golijov, but it was obvious to he could sing the Red Priest’s rep with a vengeance. Having Costanzo on board to play the title role made it easy to green-light the American premiere of Vivaldi’s Farnace, the most popular of the composer’s operas during his lifetime.

You had to be able to accept the old-timey ethos of death before dishonor to the point of absurdity if you were to reach the end of Antonio Lucchini’s 1727 libretto without guffaws or derisive laughter. Dethroned from the kingdom of Pontus by invaders from Rome, Farnace orders his queen Tamiri to kill their son and herself to avoid the disgrace of captivity. Meanwhile Farnace and his captive sister Selinda separately plot to bring down their conquerors, Roman general Pompeo and his merciless ally, Queen Berenice of Cappadocia, a gargoyle who turns out to be Tamiri’s mom.

Somehow everything sorted out happily. More amazingly, Costanzo managed to bring down the house just before intermission – bemoaning the death of the angelic little son whom he himself condemned to death!

With Costanzo singing two additional Vivaldi arias at the lunchtime concerts and Smith fronting an oboe concerto, the Red Priest explosion was major theme in Spoleto’s 2017 classical music lineup. But the countertenor continued to show his wide range. What I most regretted about skipping the final weekend in Charleston was seeing Costanzo introduce and deliver Roy Orbison’s deathless “Crying!” An 11-piece ensemble, including Palmer and Nuttall, was weeping behind him. Or maybe not.