Review: Confederates at The Arts Factory

By Perry Tannenbaum

Symmetry, parallelism, continuity, and evolution are intricately interwoven throughout Confederates, Dominique Morriseau’s comical and sometimes farcical drama of 2022. The Charlotte premiere, now at the Arts Factory, comes to us less than two years after its Off-Broadway premiere in a highly polished, smartly aware Three Bone Theatre production.

Morriseau’s symmetry isn’t subtle: it hits us straight in the eyes the first time we see Zachary Tarlton’s scenic design. Split down the middle, the Arts Factory stage gives two eras and two institutions equal play in an intimate black box format. One side evokes Civil War slavery on a Southern plantation, while the other half introduces us to contemporary academia.

We alternate between settings, starting with Sandra, a modern tenured Black professor, proclaiming her outrage and sense of violation in vivid terms – yet with the poise and sleekness of a contemporary college lecture accessorized with slides. From that peep into scandal in present-day academia, we flash back to the slave quarters of Sara as her brother Abner sneaks into her bedroom through a concealed trap door.

Sandra has been maliciously targeted by a student or teacher who pasted a demeaning old Civil War photo of a bare-breasted black wetnurse suckling a white baby – with Sandra’s face photoshopped to replace the original slave’s. Jumping to conclusions or instinctively making connections, we’re apt to immediately believe that Sara was that nurse. Abner has volunteered for the Union Army and has been wounded in battle, so as she sews up Abner’s wound, the subject of Sara’s nursing skills is inevitably addressed.

Sara’s skills and ambitions extend further. Dangerously. She has already learned how to read, breaking one terrible white taboo, and she wishes to nurse and fight for the Union alongside her brother – to learn how to fire a rifle right now. That’s a pill Abner can’t easily swallow.

Otherwise, the two women have separate storylines until Morisseau split-screens them together at the end. Portraying Abner in his Three Bone debut, Daylen Jones is the first subordinate character to cross the invisible line between pre-Emancipation Dixie and the hope and refuge of modern-day academia. Shedding his rags and his Union blue greatcoat, Abner becomes the aggrieved Malik in today’s world. He’s obviously a gifted student, and his gripe with Professor Sandra is that she grades his papers more harshly because he’s Black, protecting her immunity from being charged with favoritism.

Seeing that there are only Black females on faculty – and no men – Malik feels doubly oppressed by bias in academe: racial bias compounded by gender bias. Notwithstanding her starchy professional manner, Sandra is more of a crusading sociologist than a sober judge. So she may indeed have fallen prey to the trope heaped upon oppressed races and genders that says, “If you wish to be treated as an equal, you need to be better.” Pragmatic? Sure. But for a gifted scholarship student seeking to maintain his A average, cold comfort.

We eventually see that there are four characters on each side of the time divide, three of whom repeatedly change costumes to play double roles. Before and after we can tally all this, director DonnaMarie and sound designer Tiffany Eck place two snippets from Nina Simone’s “Four Women” at strategic spots in their playlist, layering on extra meaning – and mythic aura – during scene changes.

If Jones can be labeled as two provocatively different militants as he roams back-and-forth from opposite sides of the stage, then Holli Armstrong (also on my radar for the first time) can be regarded as two variants of an imperfectly enlightened white racist. She is most exaggerated and hilarious on the Southern plantation as Missy Sue, the master’s daughter, when she comes back home as an undercover born-again Abolitionist. It is Morisseau as much as DonnaMarie who is prompting Armstrong to bring a Gone With the Wind air-headedness to Missy Sue – and a twisted lesbian desire for Sara – and she obliges with fiddle-dee-dee gusto.

She offers Sara a perk in exchange for executing a dangerous mission: if Sara will transcribe and transmit Master’s battleplans, she gets to live in the big house while Sue delivers Dad’s secret intelligence across enemy lines. Sure, that’s an appreciable upgrade for Sara, but she’ll still be a slave doing Missy Sue’s dirty work.

Armstrong discards Missy Sue’s pea-brained giddiness when she transitions to Candice, retaining her sycophant tendencies and much of her high energy as she haunts Professor Sandra’s office, working off her tuition debt and gathering gossip. Her true manipulativeness gradually emerges in successive office scenes, but Candice never becomes as juicy a role as Missy Sue is, for she somewhat downplays her suck-up moments with faculty.

Last to appear onstage, Jess Johnson draws the most balanced – and delicious – of the dual-role combos. As the master’s Black mistress, the opportunistic Luanne effortlessly sniffs out that Sara’s access to the master’s office and desk are coming at a price the newcomer must pay, possibly beyond accepting Missy Sue’s sexual advances. On the academic side, Johnson gets the most radical of costume designer Chelsea Retalic’s backstage makeovers when she becomes Jade. Professor Jade is more stylish and popular than Sandra because she’s chummier with her students and would never dream of hamstringing the Black ones.

At both ends of the stage, Johnson gets to be a wily master of psychological warfare. Both Luanne and Jade want something vital from our protagonists. Luanne wants friendship from Sara and a path to freedom, but if Sara bars the way, she can work her charms on Abner. Needing Sandra’s endorsement, Jade doesn’t tiptoe around her differences with her superior, unleashing a torrent of scorn and chutzpah that took my breath away.

Indeed, Johnson unlocks Morisseau’s grimmest joke on her protagonists. Whether you’re at the bottom of the pecking order or at the top, you’re still the most oppressed person in the room. Times have changed, but not that much.

Sara is always being pulled at from multiple directions. Abner needs to be sewn back together, Missy Sue wants to recruit her as a spy, and Luanne wants her to plot an escape to freedom. Maybe that’s why the playwright stretched out Sara’s name to Sandra for the New Millennium! Our Professor is no less pressed upon, strongly urged to re-examine her grading philosophy, softly reassured that she is more admired than she really is, and arrogantly lobbied for tenure backing. Nobody seems to really care about the bare-breasted insult that was slapped on her office door.

Neither of these roles is fun-filled, but the challenges Sara and Sandra face allow them to grow in strength and stature before our eyes. Valerie Thames and Nonye Obichere are so fiery and authoritative in their separate roles that you can comfortably watch Confederates as two separate plays without constantly considering how meanings and brilliance bounce off the facets of the two gems. Not feeling compelled to track the finer points of Morisseau’s disquisition on racial or gender bias makes it all the easier for an audience to enjoy them.

Thames effortlessly takes on the self-assurance of an established TV guest whose knowledge and viewpoint are proven commodities, wearing Professor Sandra’s celebrity status with insouciant dignity. Just watch out when she bursts into flames! Maybe run for cover.

Although Sandra’s speeches frame the drama, Obichere gets to be a more physical presence as Sara – as nurse, spy, soldier, and lover – and she navigates a far wider character arc. Hers isn’t the funniest performance you’ll find this weekend at The Arts Factory. But it’s the most vivid, shocking, and memorable.

You may leave the theater convinced that both Sara and Sandra are depicted in that horribly racist slide. But it will mean more at the end than at the beginning. The magic of Morisseau and Photoshop are both at work.

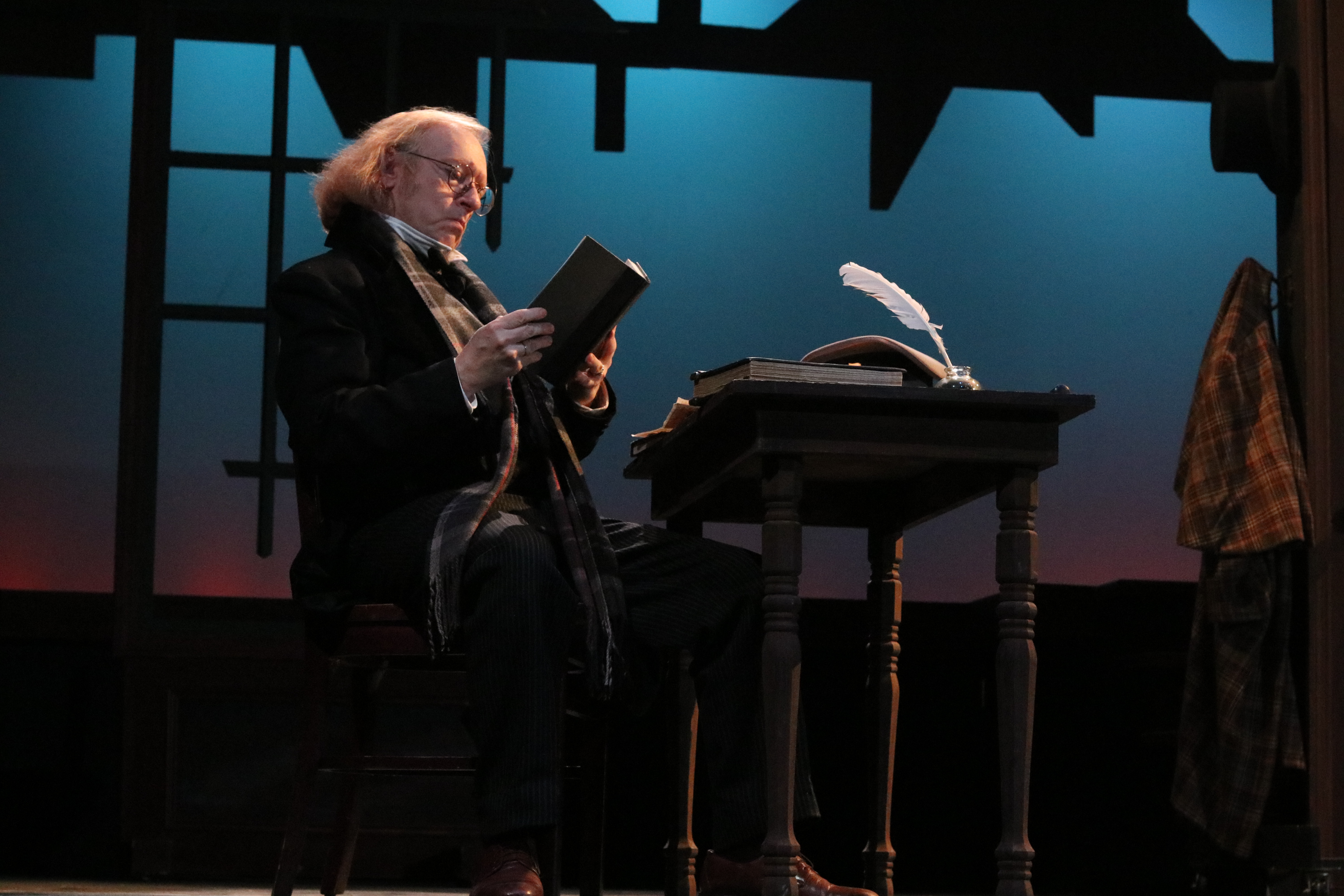

But the wonderfully avuncular Dennis Delamar as Grampa Vanderhof has a bit of an edge to him when an IRS agent comes calling about those income taxes he has never paid. There’s a “government of the people” tinge to his reaction as he demands to know how his money will be spent, but there’s also a saintly element of renunciation – for he has willfully abandoned the hustle-and-bustle of capitalism outside his home and devoted himself completely to doing as he pleases in and about his own roost.

But the wonderfully avuncular Dennis Delamar as Grampa Vanderhof has a bit of an edge to him when an IRS agent comes calling about those income taxes he has never paid. There’s a “government of the people” tinge to his reaction as he demands to know how his money will be spent, but there’s also a saintly element of renunciation – for he has willfully abandoned the hustle-and-bustle of capitalism outside his home and devoted himself completely to doing as he pleases in and about his own roost.