Review: Charlotte Ballet’s Spring Works

By Perry Tannenbaum

Go figure. On opening night of Charlotte Ballet’s Spring Works, the most famous choreographer on the program wasn’t listed in the program booklet. Nor was his dance repeated at the next three performances after the Friday opening. Unless you noticed the insert inside your program booklet, you never did know that Merce Cunningham, who would have been 100 years old on April 16, was the mystery choreographer of the night. Or that Anson Zwingelberg, Charlotte Ballet’s representative at a Centennial Celebration at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on that night, was the dancer who repeated his performance from the special “Night of 100 Solos” gala.

For those of us who did eventually discover the insert, then looked up the celebrations – in London, Brooklyn, and LA – and tracked down the Vimeo replays of the live streams, most of the mystery was solved, except for the title of Zwingelberg’s solo. Others who freewheel their spectating without consulting their programs might still be puzzling the connection between what Zwingelberrg did and the Opus.11 pas-de-deux that followed.

With my program spread out before me, I knew instantly that I wasn’t watching Alessandra Ball James or Josh Hall, respectively in their 13th and 7th years with the company and listed as the partners in David Dawson’s Opus.11. Completing his second year, Zwingelberg is best remembered for his villainous Karl in The Most Incredible Thing last March. He wore a costume then. Although credits for designing Zwingelberg’s attire were given to Reid Bartelme and Helene Jung, your initial impression of their handiwork might be to assume that Zwingelberg had escaped from a work prisoners’ detail along the margins of I-77.

In his brightly colored jumpsuit – somewhere in the neighborhood of mauve, DayGlo orange, and Band-Aid – Zwingelberg performed one of Cunningham’s less dancelike solos. Arm, hand, and leg movements had an eccentric inward quality to them, occasionally endearingly comical, emphatically anti-musical, and occasionally spasmodic and crazy. A formal onstage introduction of some kind would have helped, to be sure, although it would likely have been nearly as long as the solo.

Described as a “love letter” to Dawson’s two collaborators, dancer/costume designer Yumiko Takeshima and dancer/choreographic assistant Raphaël Coumes-Marquet, Opus.11 was unmistakably about love. Greg Haines’ hypnotic music and Dawson’s intimate lighting cast a nocturnal spell, more than sufficient to rekindle the chemistry between James and Hall. It should be familiar to CharBallet subscribers by now. If you’ve forgotten their man-goddess pairing at last year’s Spring Works, they’ve been Sugar Plum Fairy and Cavalier in Nutcracker and Peter Pan and Wendy in the meantime.

For James to reach such depths of sensuous surrender in a dance, she must trust Hall completely when she lets go. Years of dancing together have built a confidence in James that now appears to be absolute, so it’s really exquisite to see them so sinuously, emotionally, and fearlessly in action. It probably didn’t hurt that Coumes-Marquet himself was on hand to stage and rehearse this satisfying piece.

Helen Pickett, the choreographer who paired James and Hall so effectively last spring in her “Tsukiyo,” returned with the world premiere of a more complex work, IN Cognito. Dedicated to Blowing Rock native Tom Robbins with a title inspired by Villa Incognito, one of his later novels, Pickett plays with the idea of performers hiding behind their roles – yet exposing their true selves. Lighting by Les Dickert and costumes by Charles Heightchew evoked the brightness of 60’s and 70’s décor, yet there was regimentation and repetition in the early ensemble action that made me think Pickett had something pungent to say about peer groups and humdrum workplaces.

The 10 performers, including special guest Robert Plant, executed their impersonal dance moves amid innocuous furnishings. A couch, complementary ottomans, floor lamps, descending window frames and ceiling lamps defined a domesticated indoor space where people interacted without really connecting. Satire? Music by Oscar-nominated Jóhann Jóhannsson and Mikael Karlsson occasionally heightened the urgency of this dance but didn’t warm up its cold vibe. When the couch was put into service as a runway, the dancers briefly took flight.

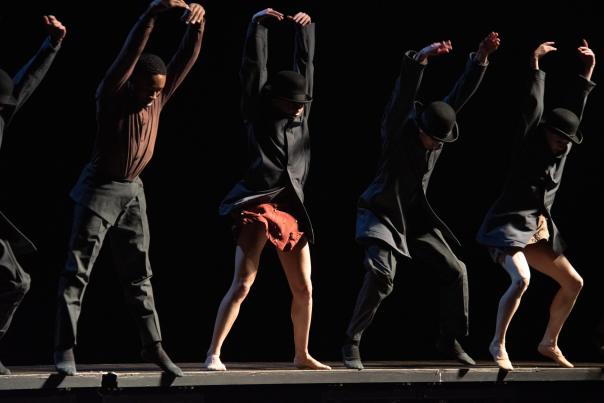

Reprising Johan Inger’s Walking Mad, CharBallet recalled artistic director Hope Muir’s triumphant arrival in the fall of 2017, when this was the opening work on her first program. Premiered at Nederlands Dans in 2001, toured by Alvin Ailey, and staged by an international who’s who of companies, Walking Mad can be anointed a classic even if Inger’s name still isn’t a household word. It features nine dancers in moods ranging from giddy silliness to deep despair – and a very versatile wall – mostly dispelling the obsessive spell of Maurice Ravel’s famed Bolero.

Replacing Ryo Suzuki, who launched the piece in 2017, Maurice Mouzon Jr. made his entrance from the Knight Theater orchestra pit, dressed in a drab overcoat and a Magritte bowler hat, the first of numerous bowlers we would see. No music yet, wall only dimly evident in the gloom. Mouzon and Sarah Hayes Harkins would dominate the pre- and post-Bolero moments, the first in silence and the moody finale set to Arvo Pärt’s “Für Alina.” Withdrawn and grumpy, Harkins wouldn’t accept Mouzon’s coat, letting it drop to the ground.

The first uptick in intensity comes as the simple wall springs to life, plowing Mouzon towards us. Then the mood also begins to shift when there’s a breakout of silent vaudeville comedy at opposite ends of the wide wall, our first visual confirmation that other dancers are conspiring in the comedy. Silent film comedy, you might say, appropriate for when Bolero was premiered in 1928. Doors appear in the wall. Another uptick: Men dressed in dopey maroon party hats begin to chase around and through the wall. Women in similar hats, looking equally dopey, join the party.

We tend to forget – or not even know – that Ravel’s Bolero actually began as a ballet. But not like this!

Abruptly, the wall was bent into a perpendicular shape, the music was muted, and Elizabeth Truell dominated the enclosure, by turns unresponsive, terrified, and violent toward the men who tried to reach her. She was clearly the maddest of Inger’s walking mad, conceivably in an isolation ward, and most bizarre when she and her partners suspended themselves in the corner of the half-folded wall. Slamming all three of his dancers against the wall in this segment, the choreography had a sprinkling of French apache as we awaited the return of the Bolero.

The logic seemed to be that the music returns to full volume when Truell peeps over the top of the wall, but that logic didn’t hold in this surreal world. Gradually the music and the snare drum’s tattoo returned. After an old vaudeville mirror shtick early on, Ingel had laid part of the wall down like a palette and turned it into a slightly elevated dance floor. Now the whole wall came down, and in a Kafkaesque sequence, the former partyers all returned in Magritte bowlers, dancing in manic unison rather stumbling glee. in the process, the mob tormented Mouzon, tossing off their overcoats as Bolero roared to its end.

Applause inevitably greeted that wild moment, although Mouzon remained spotlit downstage awaiting Pärt’s wan piano sonata to cue up. With business between Mouzon and Hayes centering on his coat once again, the two dancers came marginally closer to connecting. If Mouzon had strengthened and persisted in his overtures for an hour or so, the diffident Hayes might have relented a bit, but the young man didn’t have that kind of resolve.

You could have called Mouzon’s exit Chaplinesque if it had a sunnier energy – or any true animation, though he did scale to the top of the wall and balance himself there. Instead of jumping or throwing himself off the edge, Mouzon merely leaned forward and fell out of sight. Classic.