Review: Mrs. Doubtfire at Blumenthal Performing Arts

By: Perry Tannenbaum

Pardon me a second, but I seem to be noticing stretch marks on my suspension of disbelief. Three nights before the curtain rose on the touring version of Mrs. Doubtfire that rolled into Belk Theater, I saw a rather fine production of Twelfth Night across town at Central Piedmont College. Since both of the brief runs include at least one matinee between now and Sunday, my experience of seeing two wives who fail to identify their true husbands can be intensified, compressed into the space eight hours, if you wish, after my relatively relaxed 75-hour exercise.

In Shakespeare’s 1601 comedy, Olivia marries Sebastian – much to his delighted befuddlement – the twin brother of the disguised Viola, the woman who has actually smitten her. Later, on the same day of her wedding to Sebastian, whom she believes is Caesario (!), Olivia encounters Viola still in her disguise, who has the gall to deny they are married!

In the 1993 film starring Robin Williams and in the Broadway musical adaptation of 2021, the mix-up occurs earlier in the action – but after a lengthy Daniel-and-Miranda marriage that has produced three darling Hilliard children from its intimacies and one bitter divorce from its hostilities. The set-up for Daniel’s makeover zoomed by so quickly on opening night that, aside from throwing his son a super birthday party despite Mom’s insistence that he was grounded for his poor school grades, I really didn’t grasp how he had gotten Miranda so pissed.

Not that I blamed her. Rob McClure as Daniel was so hyper, manic, and over-the-top in his early scenes, like a cut-rate Robin Williams in his early nanu-nanu years, that it was easier to wonder why Miranda had married him than why she would file papers. This is one grating, irritating, self-absorbed dude who is spoiling his kids, always “on” in his daddy role, like a badly misfiring Williams improv shtick on latenight TV. Until suddenly, like in an epiphany, he hears the family court judge’s decree and finds himself poignantly pleading for a greater share of his children’s lives.

his is only the beginning of Daniel’s lightning-quick transformation, for it isn’t going to be merely skin- or mask-deep. In Mrs. Doubtfire, to be fair, Daniel is really trying so hard to deceive Miranda – and regain his precious access to his kids, who clearly matter more to him than their mom. So he commandeers all the advanced mumbo jumbo of modern makeup science via his gay brother Frank and his partner Andre. A true artist, he proceeds to artificially boost his bustle and decks himself out as a ragout of Miss Marple, Margaret Thatcher, and Julia Child. With a Scottish accent.

Meanwhile, our playful Daniel sabotages his ex’s email search for a nanny (a bit nasty, really) and moves himself to the head of the line of nanny telephone applicants, impersonating all the losers before shining as Mrs. Doubtfire, a name he improvises on the spot. Cunning and very much in character, except that he’s suddenly catering to his ex-wife instead of blithely ignoring her.

The nanny who appears at the Hilliards’ threshold for “her” in-person interview not only fools Miranda, he also fools his three kids. Well he might. This nanny is not at all Daniel anymore. The voice, the tempo, the personality, and the parenting approach are all radically different. Instead of his previous happy-go-lucky, laissez-faire practices, he now leapfrogs Miranda and becomes sterner, stubborner, and more demanding than she ever was.

Conceived as a stopgap avenue to his children while he regains Miranda’s trust, Mrs. Doubtfire succeeds beyond Daniel’s dreams. She’s a godsend, not only as a caretaker, but as a friend, confidante, and a chef! Miranda cannot remember when she was so happy and wouldn’t ever dismiss Mrs. D in favor of Daniel, no matter how thoroughly or sincerely he has reformed by the time the judge reconsiders custody.

This irony brings no consolation to the kids. As long as the Mrs. Doubtfire ruse continues to deceive them, they are missing their dad. The son, Christopher, has lifted his grades under the new nanny’s guidance, but he still blames himself for the divorce.

So it’s a mercy that Chris and his older sister Lydia accidentally figure it out after a few weeks. A louder tinkle in the toilet on opening night would have made it clearer how this happens.

Otherwise, the show ran better than I expected, rewarding my suspended disbelief with some zany antics and absurd predicaments. Thanks to a humorless family court social worker and an equally stolid TV showrunner, who merely doesn’t display her amusement, Daniel is forced to portray himself and Mrs. Doubtfire simultaneously on two occasions.

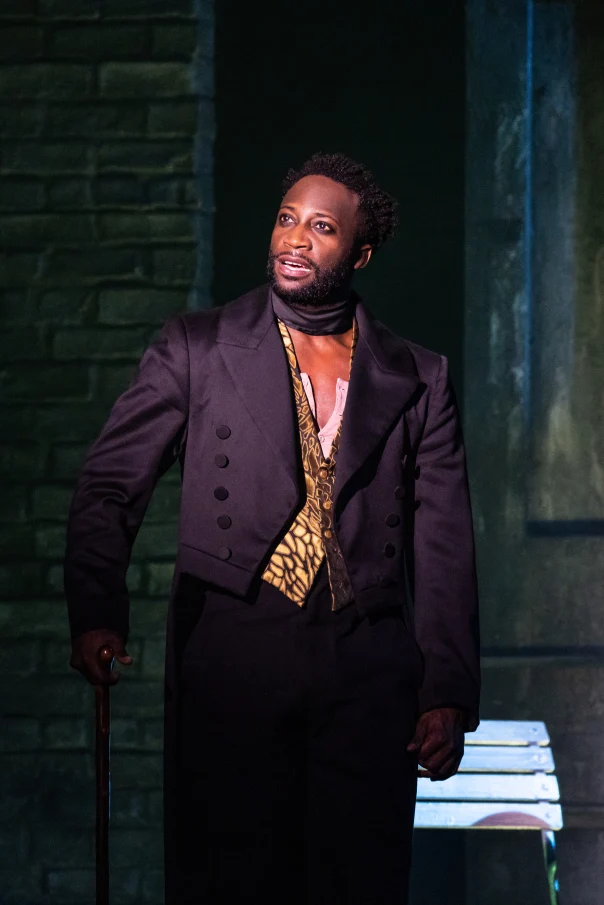

These crises force Daniel to enlist emergency assistance. When Romelda Teron Benjamin pops up as the frightfully upright Wanda, the social worker, for a home visit at Daniel’s shabby new apartment, Frank and Andre also show up fortuitously when Wanda wishes to interview both Daniel and Doubtfire. Aaron Kaburik as the brother is the more frantic of Daniel’s speed dressers, unable to tell a lie without raising his voice to fortissimo. Nik Alexander as Andre is the calmer and cleverer of the two, with a soupçon of flare, saving the day by secretly whipping out his cellphone.

Daniel’s second crisis builds slowly to a wonderful catastrophe as Stuart, the hunky new boyfriend, invites Mrs. Doubtfire to join him and the family to celebrate Miranda’s birthday – at the same restaurant where Daniel must meet with Ms. Lundy, the TV producer, to discuss a new series built upon his improvised personae. Once again, Frank and Andre are recruited for the quick changes – maybe in the ladies’ room. Fearing what Mom will or won’t see when she goes to see what has become of Doubtfire, Giselle Gutierrez and Sam Bird (alternating with Axle Rimmele) as the elder sibs must spring frantically to the rescue, reassuring a dubious Miranda that all is well.

McClure does his best work during this hectic denouement, and against all odds, we don’t absolutely despise Maggie Lakis as Miranda, though we’re rooting against her all evening. She and Benjamin eventually melt appealingly. Aided by Daniel’s conspicuous indifference toward his ex, despite Doubtfire’s meddlesome jealousy, Leo Roberts gradually gains our favor as Stuart, even if he is pumped-up and comparatively normal.

Music and lyrics by Wayne and Karey Kirkpatrick do little to elevate or damage the script adaptation by John O’Farrell and Karey K, which not only gives Andre a cell but equips the Hilliard home with wi-fi and spoils the kids with various screens, apps, and video games. No melody stuck with me, but I liked the energy of “Make Me a Woman” for Daniel, Frank, Andre, and ensemble. “I’m Rockin’ Now,” with Mrs. Doubtfire fronting the ensemble, brings us handsomely to intermission.

Two other comic gems can be commended, Jodi Kimura’s stone-faced turn as producer Janet Lundy and David Hibbard’s lachrymose portrayal of Mr. Jolly, the kiddie TV host that Daniel is destined to replace. Hibbard is like a Captain Kangaroo who long ago lost his hops, hopelessly lapsed into senility. It was generous of the writers to keep Jolly employed on the new show.