Review: Moulin Rouge! The Musical! at Belk Theater

By Perry Tannenbaum

Even before the first downbeat, the musk of forbidden fruit fills the air at Belk Theater each night as Moulin Rouge! The Musical! readies to detonate. Against a scarlet backdrop and under a proscenium studded with vanity bulbs and panning red spotlights, scantily-clad chorines slink onstage, showing limbs and cleavages like ladies in Amsterdam’s red-light district slyly advertising their merch. Elegant tuxedoed gentlemen puffing on cigarettes enter at the opposite end, consumed by each other nearly as much as by the ladies’ legs.

The ban on taking photographs, policed by Belk’s ushers wielding official signage, is already in force as soon as the first glove and high-heeled shoe come into view.

Like our more raucous welcomes to Cabaret and La Cage aux Folles, what follows in leering silence is sexy and showbizzy,. The aroma of illicitness only increases when the music kicks in – unmistakably purloined from the Top 40 pops charts as soon as we hear “Voulez-vous couchez avec moi, ce soir?” for the first time. Why trouble to compose fresh tunes, like John Kander or Jerry Herman, when you can steal or lease pure gold from a multitude of hitmakers and hire a team of co-orchestrators led by arranger Justin Levine to stitch them together?

That’s what book writer John Logan has done in adapting and updating Baz Luhrmann’s gaudy 2001 film, with costume designer Catherine Zuber and choreographer Sonya Tayeh adding their sinful embroidery and panache. All of this talented team knows that mercenary greed is as much at the heart of Moulin Rouge as glitter and concupiscence. Labelle’s “Lady Marmalade” will soon be followed – inevitably – by Barrett Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want).”

Our beautiful and consumptive heroine, Satine, wants to sell herself to the lecherous Duke of Monroth, but only because she mistakes the handsome young Christian, a budding songwriting genius from Ohio, for her buyer. Christian is no less smitten by Satine, but his prime motive for invading her boudoir, after witnessing her killer cabaret act, is to sell her on a musical show he has written with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Santiago, a dashing Argentinian dude.

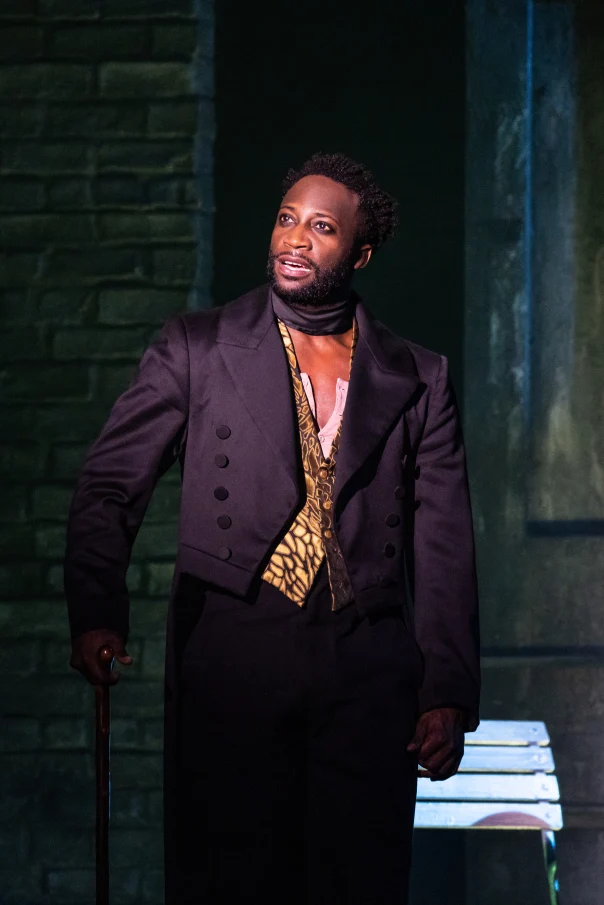

The nightclub glitz is interrupted by a detour to Bohemia, where we catch up on the Christian’s backstory with Toulouse-Lautrec, and preceded by the commerce behind-the-scenes between the two charismatics in the story – the predatory Duke and club owner Harold Zidler, our wicked emcee. Zidler, portrayed with garrulous savoir-faire by Robert Petkoff, hypes and sells his jewel’s charms, wheedling and boasting as he pimps. Since the financial fate of Moulin Rouge now depends on Satine’s success as a temptress, Zidler’s domineering mode is reserved for her.

Petkoff is marvelously matched with Andrew Brewer as the Duke. With a sinister sneer, Brewer aristocratically assesses and stalks his prey, hardly troubling himself to move around or give up his proprietary lounging position. Until he strikes like a snake when he takes his turn backstage in milady’s boudoir. In the wake of Satine’s onstage glitter – including “Diamonds Are Forever” morphing into “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” before swerving into “Material Girl” – the Duke answers brutally with a Rolling Stones medley. Brewer pounces on “Sympathy for the Devil” and builds from there with “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” and a climactic “Gimme Shelter,” maybe the most savage and primal track in the history of rock.

If that weren’t enough contrast to dramatize the Duke’s first big splash, consider the sweetness of Christian Douglas as Christian, serenading Satine with Bizet, Offenbach, and “La Vie en Rose” during his pitch. That’s the business end of his visit after springing a new song on Satine that he has written just for her, Elton John’s “Your Song.” Christian is also a crack lyricist. Back in Montmartre, he’s doctoring a Toulouse throwaway into promising shape as “The Sound of Music.”

Lowered from the flyloft on a decorous trapeze after her extended build-up, Gabrielle McClinton gets every lift she could possibly need from director Alex Timbers’ staging to bedazzle the Duke, Christian, and her breathlessly salivating audience. To me, she’s a letdown in more ways than one. Given a megamix that evokes Marilyn Monroe, Madonna, and Beyoncé in a matter of minutes, Satine should be a goddess who commands the leading men’s adoration. But instead of mesmerizing, McClinton is… meh.

It would be hugely consoling to be able to report that McClinton’s tearjerking efforts as the dying Satine are any more riveting than her diva moments. But there’s a bit of a plot megamix going alongside the pop megamix, so McClinton’s opportunities to rouse our empathy don’t quite keep pace with Mimi’s in La Bohème or Violetta’s in La Traviata. Christian has framed what we’re watching as his story and Zidler wants everyone to care that the fate of the Moulin Rouge hangs by a thread.

Our wicked emcee is augmented by the lowlife charms of Nick Rashad Burroughs as Toulouse, Danny Burgos as Santiago, and Sarah Bowden as Nini, Satine’s sexy sidekick: reminding us that love and art desperately for sale. So there would be barely enough room for Satine to be both Mimi and Sally Bowles – or Violetta and Gypsy Rose Lee – even if there weren’t more than 70 songs on the playlist to navigate.

But there are more than 70 songs swirling at us, some on replays. Paradoxically that’s what saves this Moulin Rouge superstorm from itself despite the vacuum at its vortex. The fun is not only in the pacing, the spectacle, and the jets of confetti that that tops off Zidler and Luhrmann’s circus style of cabaret. It’s in our efforts as well, episode after twisted episode, to keep up with the anachronistic onslaught of melodies and lyrics that pelt us throughout the evening. By hearkening back to 19th century hits at one end of the spectrum and contemporary sounds at the other end, this epic playlist is cunningly engineered to confound.

Whether you are old or young, devoted to pop hits or the classics, whether or not you remember when rock was young or even have a clue what Tin Pan Alley was, you will face moments at Belk Theater when you’re asking yourself: have I ever heard this song before? and what the hell are they playing now? Because its score thrusts you far outside of how you normally absorb a musical, casting you out into the realm of memories, half memories, and speculation, Moulin Rouge succeeds at sucking you in. There’s no songlist in the playbill to cling to as you swim this ocean.

Even if you’re fully versed in Luhrmann’s film, you will likely be cast adrift or taken by surprise, for Logan and Levine haven’t stood pat. Not only Beyoncé, but also Pink, Sia, Lorde, Katy Perry, Britney Spears, Rihanna, Adele and others are mixed into the fresh brew. And Lady Gaga!?!

If you’re a Broadway or jukebox musical maven, there’s another sort of question you’ll be asking yourself. How did Elton John’s “Your Song” get in here when Sir E never had the chutzpah to put one of his megahits in any of his own musicals? Good grief, they actually got the rights to perform part of a Beatles song?

Teasing you out of thought on your drive home, you will likely continue pondering what you heard or may have missed inside the lacy valentine world of Moulin Rouge. Yes, Elvis and the Everly Brothers were covered, but what about Gershwin and Cole Porter, Charlie Chaplain and Fats Domino? Likely you’ll shuttle back to remembering that Nat King Cole and Whitney Houston were enfolded in this musical’s fond embrace. There were whiffs of Marilyn Monroe and Madonna.

That’s when you realize that Satine and the Moulin Rouge nightclub – the red windmill, if you need a translation – swept you away after all.

That opens a path for Manna Nichols to sing her solos and duets as Tuptim with liberated strength, expanding upon the intelligence that was always hers when she presided over the “Uncle Thomas” ballet. Kavin Panmeechao adjusts beautifully as Lun Tha in the duets, not quite as regal as his lover but admirable in his steadfastness.

That opens a path for Manna Nichols to sing her solos and duets as Tuptim with liberated strength, expanding upon the intelligence that was always hers when she presided over the “Uncle Thomas” ballet. Kavin Panmeechao adjusts beautifully as Lun Tha in the duets, not quite as regal as his lover but admirable in his steadfastness.