Review: MJ The Musical at Belk Theater

By Perry Tannenbaum

Whether it was his skin, his sunglasses, his surgeries, or his sleepovers, Michael Jackson always gave his fans – and his detractors – plenty to think about aside from his music and his iconic videos. Even if you tried to maintain ignorance or indifference, there were just too many of him to ignore. He seemed to be everywhere, all the time, always visibly troubled and in flux. The loudest soft-spoken person we’ve known: the most grandiose hermit, progressively weirder and more deformed as the years went by.

So in condensing the King of Pop’s life and art into the 150-minute MJ The Musical, without plunging into inconvenient truths that might revoke her “Special Arrangement with the Estate of Michael Jackson,” script writer Lynn Nottage had to look very, very carefully for a place where she could begin – and a place where she could discreetly and dramatically end. A two-time Pulitzer Prize winner (Ruined and Sweat), Nottage knows her way around the theater, so she chooses wisely and safely.

Approaching its 700th performance in its current Broadway run after premiering in late 2021, the touring version has been spreading the moonwalk, the cocked hat, and the glove across our land since the beginning of August. Rounding into its second week at Belk Theater, there’s no question whether this production is a crowdpleaser. Whether or not Nottage has made storytelling mistakes or sugarcoated the facts of Jackson’s life, there’s more than enough hot smokin’ talent onstage to incinerate such nitpicking concerns in white-hot flames.

We begin in an LA rehearsal hall, where Michael, his backups, his line dancers, his handlers, and a small band are gearing for their upcoming Dangerous tour in 1992, following up MJ’s latest smash album and trying to live up to expectations created by his past glories – Off the Wall, Bad, and, greatest of all, Thriller. Ultimately, after much discussion and consternation about how MJ can uniquely open his stage show, Nottage spirals slightly ahead to the opening moments of the Dangerous tour for our ending.

By this time, there’s more than ample inventory from the Jackson 5, the Jacksons, and MJ’s solo album catalog to fuel a four-hour musical – with additional detours into the Isley Brothers, James Brown, Olatunji, and Richard Rodgers – if Broadway producers had thought those were in vogue. There’s also enough weird MJ and cosmetically altered MJ swirling around in people’s minds for media to assail the King of Pop with troubling questions and pry into his past 25+ years as boy wonder and superstar to find out what makes him tick.

As soon as Roman Banks struts into this artsy loft, he begins flipping those legitimate questions into annoyances, for we can see that the silky moves are all there before he’s halfway through performing “Beat It,” meshed with a vocal that transcends impersonation. Musicians onstage are fortified by a dozen more lurking in the orchestra, adding heft to the opening number, and the dancers are Fosse sleek and Broadway tight. This is what came to see.

So we can empathize with MJ when Rachel and Alejandro, a TV reporter and her cameraman, walk into the busy room, hoping to get an in-depth interview and a behind-the-scenes scoop. Speaking with that preternatural softness of a singer saving his voice for his next performance, MJ yields to the eager cubs – but only on the condition that they keep it strictly about the music. Banks manages to suffuse that softness with a winsome sweetness.

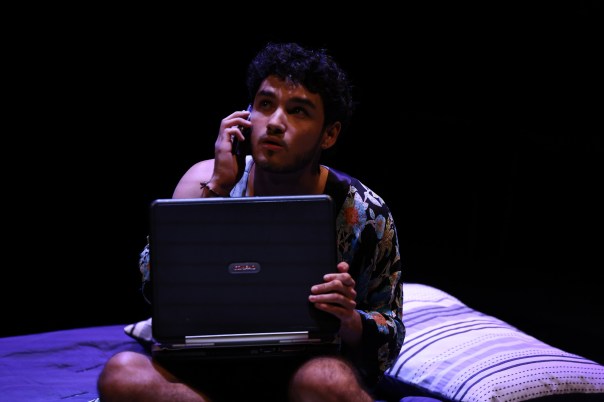

Nottage doesn’t lavish much of her MacArthur genius into Alejandro, enabling Da’Von Moody to pour a smidge of his own personality into a generic, slightly geeky fanboy. There’s a modicum of humor because Rachel, not MJ, is his boss. Here Nottage gives us some texture, bringing us an opportunistic fan-tagonist in Rachel – pushing back over and over against MJ’s restrictions, pesky, persistent, and sometimes annoying. Stepping into this crucial role on press night last Friday from deep in the list of Swing players, Ayla Stackhouse added a touch of wicked allure to Rachel.

A wisp of seduction was in the air. As a result, Banks’ continued softness and firmness may have gained fresh strength. Yet when MJ kept saying no, he seemed to be veering toward maybe.

This sensation, that we were meeting the real MJ in person as Banks shuttled between guarded and candid moments, can be partially credited to the tech crew now at the Belk. MJ often speaks the gospel of detail and perfection, but this crew fulfills it. Over the last couple of Broadway Lights seasons, I’ve become so accustomed and resigned to the sound not being right on opening night at the Belk before Act 2, if at all, that I’ve lately tolerated the problem without comment.

Maybe that’s why Press Night for this two-week run was put on hold for two performances. On ordinary opening nights, you could expect Belk’s audio crew to turn MJ’s softspoken dialogue into the sound of microwaving popcorn. This time, everything was dialed in perfectly for the critics. Moments when I might be holding my breath, bracing for sonic gremlins to afflict MJ, were simply breathtaking.

All night long, the show maneuvered deftly, revealing subtle new merits. Timeshifts between the ‘90s rehearsal loft and the eye-popping ‘60s charm of the Jackson 5, juxtaposed with the abusive Jackson household and Michael’s taskmaster dad, could become somewhat disorienting as the retrospective took off. Part of what Nottage and director/choreographer Christopher Wheeldon are trying to accomplish is steering the narrative smoothly between songs in the Jackson catalog without the storytelling stalling and landing us at a gimmicky concert.

By the time we get our bearings in Act 2, about 23-25 hits into the 40-song list of musical numbers, we realize that anybody portraying MJ is pumping out too much energy onstage, singing and dancing, for him not to be whisked off to the wings for some rest. Giving Banks some breathers is also part of the navigation calculus. No less than three Michaels were onstage between 8:00 and 10:45 at the Belk, Banks as MJ, newcomer Jacobi Kai as Middle Michael, and Josiah Benson as Little Michael, timesharing the role on tour with Ethan Joseph.

If Banks amazed me, getting every signature move and vocal intonation of MJ, moonwalking through everyday life, Benson as the Afro-coiffed Little Michael left me gob-smacked. Maybe the Jackson Estate’s worries were misdirected: who knew that the roles of MJ and Little Michael could be cast so successfully, both on Broadway and on tour simultaneously? Little Michael’s timbre had always seemed to come from a once-in-a lifetime voice since that “ABC” moment when I first heard it. Not anymore.

What could have set MJ apart from the performers portraying him at various stages of development were his songwriting gifts and inspirations, never really explored in Nottage’s book. Likely, that would have rendered the show more intimate and even more Michael-centric. We get a fairly broad tapestry instead, including glimpses of singers Jackie Wilson and James Brown, along with the ballroom grace of Fred Astaire.

The supporting cast is very fine. Devin Bowles and swing-understudy Rajané Katurah were worthiest of mention as Little Michael’s parents, Joseph and Katherine, fleshing out their marital discords. Both make good on the vocal solos carved out for them. Bowles time travels as much as Banks, portraying MJ’s stage manager, Rob, throughout the contentious rehearsal scenes. Dancers, even when supposedly driven in rehearsals to smooth out imperfections, are exemplary, living up to Wheeldon’s strict demands. Is MJ pushing his dancers too hard to reach perfection – because Dad pushed him so relentlessly? We don’t miss the emotional turmoil lurking inside this connection.

Nottage is sufficiently fascinated by the intricacies of putting a show together that she not only reveals the micro levels of drilling the synchronicity of dance routines and sweating details. She also has Michael, Rachel, Rob, and Dave – MJ’s on-edge beancounter, excellently portrayed by Matt Loehr – discussing the larger concerns, namely the architecture, pacing, and budgeting of a show.

That helps us to swallow all the action in the drab rehearsal loft before the delayed gratification of seeing the all-out “Thriller” extravaganza deep into Act 2. A whole show of such MTV-like spectacles would have cost zillions, too mind-boggling to pack onto the biggest moving van known to man. An armada of trucks and set builders would need to be deployed for a full evening of such fantastical wonder.

In many ways, Nottage and Wheeldon deliver as much as we can expect of Michael Jackson’s life and artistry onstage without surrendering the rights to the music. I’d like to think that Nottage, dealing with the Jackson Estate’s constraints, saw herself as resembling her own persistent Rachel character during the process, pushing the envelope further and further, inch by inch, as far as it could be stretched. Perhaps her Pulitzer pedigree helped Nottage to make more territorial gains and bring us closer to the real MJ than The Estate was truly comfortable with when her work began.