By Perry Tannenbaum

When the creators of South Park and Avenue Q detonated The Book of Mormon on Broadway in the spring of 2011, some people down here in Charlotte still had the 1996 Angels in America debacle in their rearview mirrors. Blumenthal Performing Arts would never have the nerve to bring such an audacious musical to Belk Theater, the Charlotte Observer taunted, because the city couldn’t handle such irreverence and foul language.

My conversations with Blumenthal brass had already indicated the opposite: they were eager to bring the show here. And they did. On the day after Christmas in 2013, Charlotte was one of the first stops for the touring version of the show. It not only came here, it stayed here for two weeks. Audiences were not at all horrified by the potty-mouthed blasphemies of the book and lyrics by Robert Lopez, Matt Stone and Trey Parker. They reveled in them, and Blumenthal staffers were soon crowing that Charlotte had been one of the most successful stops on the Mormon tour.

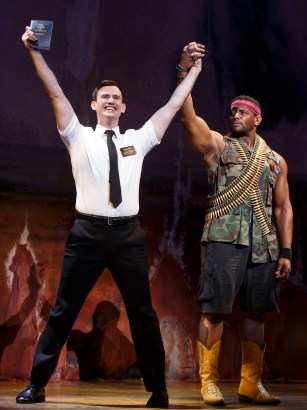

Enthusiasm for all this shrewdly crafted sacrilege has only waned slightly two seasons later. Once again, Belk Theater was sold out on press night, and it seemed like Cody Jamison Strand as Elder Cunningham and Ryan Bondy as Elder Price were offering a broader, more energized version of the Mormon missionaries’ A-team. Price is the model Mormon among the new initiates at the Salt Lake City HQ, convinced that he will draw the plumiest assignment, a mission to Orlando, Florida.

Instead, Price not only draws the least appealing destination, a Ugandan village tyrannized by a barbaric warlord, he also draws the worst possible companion, Cunningham. A pathological screw-up, Cunningham hasn’t memorized the prescribed doorbell spiel that opens the show. Actually, he hasn’t bothered to read the holy Book of Mormon, either. Worst of all, Cunningham has a tendency to panic a little under pressure, so instead of clamming up when he doesn’t know the drill, he’ll go off-script and invent stuff.

It’s at these suspenseful moments that Cunningham’s imagination will wander off into the realms of Star Wars, Star Trek, and Lord of the Rings. So if you thought a gospel where Jesus resurfaces after the crucifixion in Rochester, New York, was bizarre enough, it only gets better in Cunningham’s version. Aiming at an African congregation, Cunningham adjusts his message to address the scourges of AIDS and rape, ignoring only the repeated cris de cœur from a gentleman with maggots in his scrotum.

In contrast with Mark Evans, whose stiffness in 2013 as Elder Price reminded me of Mitt Romney, Bondy’s wholesomeness seemed more like an animated Ken Doll or the robotic Marco Rubio. An almost-inhuman dimension comes into play when he sings the delightfully conceited “You And Me (But Mostly Me).” On the other hand, Strand has magnified the slovenly boorishness of Cunningham compared to the slob next door that Christopher John O’Neill brought us in 2013.

Cunningham’s pronouncements now seem occasionally to originate from the cavern of Strand’s large intestine, yet he’s vulnerable enough to be convincingly shy in the climactic “Baptize Me” duet with his adorable convert, Candace Quarrels as Nabulungi. What really marred Strand’s performance was his microphone, which often muddied his words, provoking a couple of overheard complaints at intermission from people half my age.

Sound problems also imposed a curious time delay when we reached the comedy climax where the African villagers present their skit of the Cunningham-infused holy book to the utter horror of the Mission President. What the group was saying was often garbled by the sound system, but by the second time they mimed them, we could divine the digestive problems plaguing the disciples of Brigham Young on their westward trek.

Scott Pask’s scenic design makes the contrast between Salt Lake City and Uganda as radical as the gulf between Emerald City and the hottest region of Hell, replacing Cunningham’s visions of Lion King natural splendor with extreme urban squalor when we adjourn to Africa. The dead alligator that is dragged across the stage looks like it was dredged from a sewer before the sun dried it out.

David Aron Damane is ultra-fearsome as General Butt-Fucking Naked. Only a missionary as insanely self-confident as Elder Price could fail to see the consequences of waving the holy book in this warlord’s face. But it’s the geniality of Sterling Jarvas as Mafala, Nabulungi’s dad, that draws the biggest laughs as he welcomes our heroes to his village with the anthemic “Hasa Diga Eebowai.”

Other missionaries are floundering in Uganda, but the most outstanding Mormons play dual roles in the narrative. We see Edward Watts as Joseph Smith – in Mosaic hair worthy of Charlton Heston – before he returns in more buttoned-down stints as Elder Price’s proud dad and the even prouder Mission President. After a dazzling entrance as Moroni, Jesus’ angelic emissary to Smith, Daxton Bloomquist heads up the Uganda mission – and a wild tap-dancing ensemble – as Elder McKinley.

As the big “Turn It Off” production number cranks into high gear, it appears that Elder McKinley just might be a closeted homosexual who turns off his natural impulses “like a light switch.” With characteristic South Park subtlety, costume designer Ann Roth has the boys suddenly break out in sparkly pink vests at the height of their synchronized dance. This is just the assistance Bloomquist needs to keep the secret of McKinley’s sexual orientation secure – from children three-and-under.

![Father 4[1]](https://artonmysleeve.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/father-41.jpg?w=604)

![Father 5[11]](https://artonmysleeve.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/father-511.jpg?w=305&h=297) It’s at this point in Part 1, when hero has made up his mind in Penny’s favor, where Sidney Horton’s otherwise flawless direction falters. The knife hovers so long and threateningly over Hero that the tension breaks before the episode is really over. My surprise over this lapse only increased during Part 2, in the heat of battle, when the Colonel parleys with a wounded Union soldier that he has captured and locked in a wooden cage. Action here made me wince, leaving no doubt of the Captain’s cruelty.

It’s at this point in Part 1, when hero has made up his mind in Penny’s favor, where Sidney Horton’s otherwise flawless direction falters. The knife hovers so long and threateningly over Hero that the tension breaks before the episode is really over. My surprise over this lapse only increased during Part 2, in the heat of battle, when the Colonel parleys with a wounded Union soldier that he has captured and locked in a wooden cage. Action here made me wince, leaving no doubt of the Captain’s cruelty.