Review: Twelfth Night at the Parr Center

By Perry Tannenbaum

Shakespeare’s best comedies are bursting with multiple plots, and two of the most perfect – A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Twelfth Night – are the most dizzying and delightful. It is quite likely that the latter, later work was first performed on Twelfth Night of 1601 to celebrate the newborn century on January 5 (with a singing clown suggestively named Feste). Yet time, scholarship, and heavy-handed dramaturgy have tended to darken many modern-day productions.

That’s why the current Central Piedmont Theatre version at the Parr Center, adapted and directed by Elizabeth Sickerman, is so refreshing. Twelfth Night has at least four main plots: Viola’s separation and reunion with her twin brother Sebastian, Duke Orsino’s unrequited love for the widowed Countess Olivia (seconded by Sir Andrew Aguecheek), Viola’s crush on Orsino while disguised as his manservant, and the wicked prank concocted by Aguecheek, Sir Toby Belch, Feste, and Maria to send Olivia’s ambitious and party-pooping steward, Malvolio, to the madhouse.

Of these, the most dominant plot should be the Viola-Orsino mess, for it sprouts so many delicious complications. Acting as Caesario, Orsino’s servant, Viola is dispatched to to Countess Olivia’s manor to plead on behalf of the Duke – only to have the Countess fall in love with her. Olivia’s inclinations toward Viola/Caesario not only enflame Orsino’s jealousy, they also lead to an absurd duel with fellow coward Sir Andrew. Meanwhile, she encounters Sebastian’s close friend, Antonio, who puts all his money in Viola’s care, mistaking her for her twin. You can easily imagine what happens when Sir Andrew makes the same mistake.

Ultimately, the mistaken identities reach the giddy point where Olivia cannot recognize her own husband just hours after their marriage. Ah, a honeymoon to remember.

So to tip the balance toward empathizing with Malvolio, simply because he is incidentally berated as “a kind of puritan,” is rather perverse. Elsewhere, I’ve seen the steward outfitted with a Puritan’s hat. Far more stupidly, I’ve heard a theatre sage say Malvolio was modeled on Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, born in 1599. Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex (1485-1540), instrumental in the English Reformation, is a more feasible candidate. Sickerman not only discards such nonsense, she transports the action from ancient Illyria, at the heel of Italy’s boot, to a coastal town immersed in the Jazz Age.

Costume designer Emily McCurdy certainly goes with the Roaring 20’s flow. Orsino and Olivia could easily pass for the recently reprised Gatsby and Daisy Buchanan on Broadway, surrounded by flappers and jazzy gallants galore. The moving pieces and projections of Jennifer O’Kelly’s scenery, more evocative of summer than winter, have enough classic detailing for Viola to sit at the foot of an Ionian pillar when describing herself sitting like “Patience on a monument.”

Nor does the music veer from the vintage of Prohibition days. Montavious Blocker has choice cuts of Duke Ellington and Sidney Bechet in his soundtrack, and just a few bars of music arranger Matt Postle’s chart for “Come Away, Death,” transformed from a lover’s lament into a jivey jump tune, are enough to conclusively vanquish melancholy, injecting Feste’s song for the lovesick Orsino with catchy mischief. The debris downstage suggests an Amelia Earhart plane crash rather than Shakespeare’s original shipwreck, and Charles Lindbergh could have inspired Sebastian and Viola’s matching outfits. Except for the tacky slacks.

If you’ve seen Twelfth Night before, Sickerman cordially adds to the Bard’s dizzying layers of identity, cutting some expositional text and casting females in key roles. Not one of them is a Chickspeare alum. Saskia Lewis as Feste, Rhianon Chandler as Antonio, and Kameal Brown as the recklessly unknighted Dame Toby Belch are all QC newcomers to me. If only Aryana Mitchell, portraying Viola, had an identical twin sister to take on Sebastian!

We are centuries away from the Protestant Reformation or the English Restoration, although Sickerman seems to beach the sibs closer to the Pilgrims’ beloved Plymouth Rock than to the Adriatic coast. Such oceanic distancing frees Malvolio from a dungeon of scorn when Central Piedmont’s plotters and nobles plunk their preening steward into a humble barrel to punish his prudery.

He isn’t the clown among the comical group, but Sickerman allows Truman Grant as Malvolio to loosen up, so that his usual rigidity is now almost elegance, mockable now as uppity pretense. Another sign of Sickerman’s lighthearted touch: her pick for the incredulous Sebastian is Timothy Snyder, who is at least a foot taller than his “twin.”

The disparity was so great, that I didn’t catch on at first. Brown’s outfit as Dame Toby, more like Miss Marple than a Falstaffian drunkard, compounded my early confusion, making me feel like newbie to the comedy while I got oriented. Struggling to remember a single instance when the euthanized CPCC Summer Theatre ever presented such a challenging comedy, I stumbled upon another reason why this excellent production was so refreshing.

All the cast was youthful, like the summer college grads who swarmed to Charlotte during CP summers to launch their pro careers. Not one old-timer in the bunch!

As a result of coping with all the period, costume, and gender changes, my disorientation was dispelled at the same time that I was learning to trust the youngbloods performing at CP’s New Theater, which has thankfully replaced panoramic Pease Auditorium but lamentably failed to showcase nearly as much CP talent. The mental training wheels that I had doled out to all these student efforts quickly flew away.

But along with a lightened, more secular and decadent Malvolio, there was newfound pleasure in the other creatures onstage who no longer needed to orbit around the self-absorbed steward. The Malvolio miasma that I’d felt since my first encounter with Twelfth Night in a college Shakespeare seminar, taught by a professor victimized by the prevailing obsession with the “puritan,” finally evaporated.

Twelfth Night, or What You Will has always been an awesome comedy for me. Now it was fun. I’d barely appreciated the bounty of fascinating character sketches that the Bard serves up here.

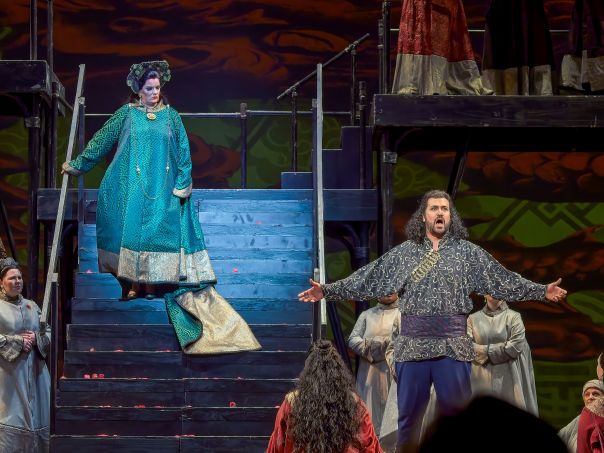

Now Viola is the patient, softspoken eye of the storm, and Mitchell is keenly sensitive, alternately anguished and bemused by all the passion and folly that surround her. Mitchell’s discreet takes, shared with us, make her a sort of co-emcee with Feste, though Sickerman asks too many eyerolls from her. Fitz Fitzpatrick is only slightly over-the-top with the lovesick gushings of Orsino, chiming well with a lounging Duke or a mob boss. Yes, that sleek robe has a Godfather aura before we see Fitz in the Gatsby threads.

As Olivia, Arianna Zappley does not yield at all to Fitzpatrick in regal dopiness. The two are as perfect a matching pair as the twins, made for each other, yet both are insanely lucky to land one of the sibs. Rounding out the symmetry of the two couples as Sebastian is the disproportioned Snyder, who does manage to nearly equal the calm of his diminutive twin – even though the Illyrians mistake him for her over and over. Playing Sebastian’s closest friend, the wrongly arrested Antonio, Chandler helps the prisoner to emerge as a neat counterweight to Malvolio, who is rightfully chastised for his presumption, though the penalty is too harsh.

There’s a little more slapstick flavor to the motley crew who bedevil Malvolio – and a bit more spice. Evelyn Ovall as Olivia’s waiting-gentlewoman Marie, who forges her mistress’s handwriting in the billet-doux that entraps the detested steward, is destined to marry Brown as Dame Toby. I’d like to think Ellington and his orchestra would have consented to play at the wedding reception, but I’m not sure.

Dopiest of the conspirators and clearly the least self-aware is Salim Muhammad as Sir Andrew, usually exiting with an absurdly military goosestep. In his challenge to Caesario/Viola, Muhammad now dons boxing gloves instead grabbing a sword, magnifying his ineffectuality with his effeminate pawing as he briefly combats the well-matched Mitchell.

Lewis effortlessly steals nearly every scene she appears in as Feste, convincing me along the way that this clown was intended to upstage all others. Not only does Feste sing lyrically and wittily – compared to the other lovers who barely stammer their effusions – she proves to be a better actress than the leading lady, Viola. Visiting Malvolio at the mouth of a barrel he believes is dark hell, Feste gives bravura performances as Sir Topas, a parson supposedly sent to determine how mad this lunatic is, interspersed with imitations of a sincere jester. Lewis cackles and coos this cruel vaudeville as bewitchingly as she swings death, ranging further than anyone else.

Photos by Perry Tannenbaum