Review: The Tempest at The Gettys Center

By Perry Tannenbaum

Rarely mentioned among Shakespeare’s best comedies, let alone among his best works, The Tempest maintains an enviable popularity within the Bard’s celebrated canon. The current Free Reign Theatre presentation at the The Gettys Center in Rock Hill marks the seventh local production to appear in the Charlotte metro within the past two decades – Actors from the London Stage visited with an eighth in 2011 at UNC Charlotte.

Upstairs in the Getty courtroom turns out to be a perfect backdrop for this masterwork of measured retribution. In the misty annals of Shakespearean scholarship and criticism, The Tempest has often been singled out as the Bard’s final and most perfect work. More important to most theatergoers are the notions that Shakespeare places himself in the role of Prospero and that Prospero’s renunciation of the magic arts is the playwright’s farewell to theatre at the same time.

Under the direction of David Hensley, with costumes by Gina Brafford, it often looks like the retiring Bard had a notion to syndicate his valedictory work as an ancestor of Gilligan’s Island. Though Prospero was presumably shipwrecked in the Aegean or the Mediterranean, his most distinguished guest, King Alonso of Naples, seems to be outfitted with hand-me-downs that Gilligan or The Captain will don centuries later.

Not the first to impress upon his audience that Prospero is the main architect of the action that ensues on his tropic isle, Hensley has his protagonist, played by Russell Rowe, waving a magical illuminated staff to summon up the mighty winds, rains, and seas. Now we can adjourn to Shakespeare’s opening scene as a panicking Master and Boatswain stand on a ship’s deck trying to right their way in this tempest with a ridiculously puny captain’s wheel.

Prospero’s power on his island is vast, for he holds the fairy Ariel and the deformed monster Caliban as his slaves. Since all the action we see follows Prospero’s basic design, it’s not too outlandish for Victor Hugo to have claimed that through Caliban, Prospero rules over matter, and through Ariel, over the spirit. His sovereignty certainly extends beyond his island to the seas he sets in turmoil.

With Ariel’s help, Prospero can separate the arrivals of the servants from the shipwrecked seamen and the corrupt nobility of Naples and Milan from Prospero’s chosen heir, the virtuous Prince Ferdinand of Naples. He plans to match Ferdinand with his daughter, Miranda. On hand to help Ariel keep Prospero’s fugal design flowing smoothly are Juno, Ceres, Iris, and numerous other nymphs and spirits.

But omniscience is far from Prospero’s grasp, so Shakespeare can artfully engage us with wisps of drama and suspense. Prospero cannot be sure that Miranda and Prince Ferdinand will take to one another. Furthermore, Prospero must be on guard against Ariel and Caliban, both of whom chafe under his dominion – respectively capable of escape and rebellion.

Watch carefully, and you’ll notice how Shakespeare flips these prospects for suspense and drama into comedy.

Armed with Prospero’s vatic powers and steeled with the usurped Duke’s determination to restore rightful rule in distant Milan and Naples, Russell Rowe is slightly above the action, never clownish or fully mundane. He participates in the romantic comedy by scheming to inflame Miranda’s ardor for Ferdinand by subjecting the Prince to the humiliations of enchantment and daylong labor.

Smitten by each other almost as soon they meet, Hannah Atkinson as Miranda and KJ Adams as Ferdinand convincingly demonstrate the needlessness of Prospero’s stratagems – Ferdinand is promising to make Miranda the Queen of Naples less than 75 lines after he first appears. To be frank, the old magician, for all his learning and wisdom, has nearly forgotten his own youth. So the joke in also on him! Of course, it does take a little imagination to conjure up a virginal 15-year-old who has never seen any other man than her aging father and the “mooncalf” Caliban. As a result, Atkinson gets more unique traits to distinguish herself with.

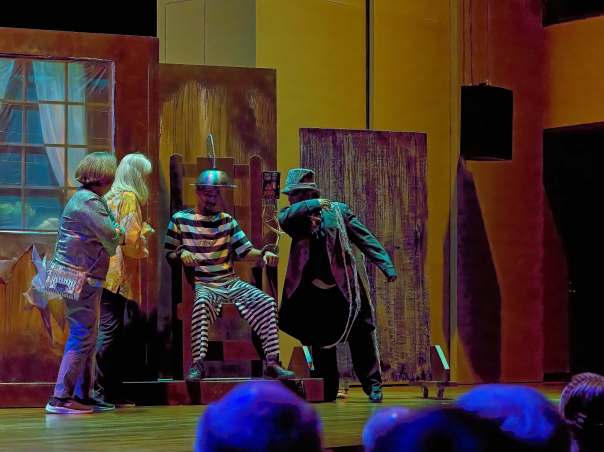

With Caliban, played by the versatile Robert Brafford, Prospero can take a more laid-back and confident attitude, relying on the weird mutant to make a fool of himself in his rebellion. Latching on with his blue paws to Bronte Anelli as the drunken jester Trinculo and Spirit Craig as the marginally more sober butler Stephano – and mooching an occasional gulp from their ample bottle of booze – Brafford wastes no opportunity to subtly reassure us that, despite his mighty grievances, Caliban is foredoomed to failure.

Ariel, the vivacious Rebecca Viscioni, does confound the help, pulling out an invisible voice imitation shtick that, to my mind, James Barrie poaches in Peter Pan. Regardless, it is curious to note that both Ariel and Peter were written for men and usually played by women.

The “airy spirit” has more urgent places to intervene after wrecking the ship and sorting its survivors. Chiefly, she is needed – seemingly more than Prospero knows – to keep things flowing properly among the shipwrecked royals. Complacent on his throne, which is now reduced to a collapsing chair with cupholders, Nathan Stowe as King Alonso seems blissfully unaware of the treachery up in Milan. Stowe’s discomfort and disorientation in Shakespearean pentameters adds a light patina of comedy to Alonso and helps us to believe that he’s oblivious to the lurking threat in his own family.

Adding very little to the comical aura of Alonso’s complacency, Ross Chandler as the King’s brother needs a bit of cajoling from Antonio, the usurping Duke of Milan, to act on his designs on the Neapolitan throne. Fortunately, David Eil has a superabundance of shiftiness and malignity, enough malignity to be noticed not only by Alonso but by every citizen from Naples to Milan. Or by satellite.

Also on board the foundering ship, fortunately enough, is Emmanuel Barbe as a rather slick Gonzalo – former councilor in service of Prospero, who supplied the usurped Duke with necessary provisions, plus the cream of his precious library, when Antonio cast him off to sea 12 years earlier. Rejoining him onshore, we see that Gonzalo now serves King Alonso, so Gonzalo is now ironically saving his own life as well as his monarch’s with those mystic books.

For Sebastian and the never-sated Antonio mean to slay them both, not with ancient sword blades drawn from waterlogged hilts but with a 9-iron and a wedge extracted from a golf bag, a bit more slapstick. Bludgeoning rather than stabbing or beheading seems to be the plan and we are in some suspense – less with golf clubs than with drawn swords – as to whether Prospero has foreseen this impromptu assassination plot.

There is one whispering considerably earlier between the rightful Duke and Ariel in the unusually detailed stage directions, so if we’ve remembered that brief moment, there’s hope that help is on the way for the feckless King and Prospero’s loyal benefactor. But as those swords/clubs are held high over the sleeping heads of Alonso and Gonzalo, suspense mounts, thanks chiefly to Eil. So if Prospero doesn’t have the smarts to anticipate what’s happening, we must trust his Ariel to save the day.

The oft-hailed perfection of The Tempest is two-fold: aside from artistic perfection acclaimed by critics, it is also Shakespeare’s most perfectly preserved script, the lead-off play in the famed 1623 First Folio collection of 36 plays, meticulously edited by the Bard’s fellow actors, Philip Heminges and Henry Condell. Hence the unusual profusion of stage directions when you encounter the text.

Hensley and his cast do a fine job in making those generous stage directions disposable, and his careful cuts in the script, though occasionally robbing us of its full lyric pleasures, are laudably protective toward the multiple storylines. Having seen The Tempest five times before and having read/studied it more than once, I’m not bowled over by the blizzard. My worries are for those plunging into The Tempest for the first time. That little prelude with Prospero is helpful, but quite a deluge of entrances ensues.

So it was disappointing not to find any roles named in the printed program on opening night, only the alphabetized names of the actors. Clicking on the QR code is helpful, pairing faces with their roles, but again in alphabetical order – without the helpful capsule descriptions Shakespeare provided. Those would be valuable at intermission for newcomers who might still be struggling to sort out Alonso, Antonio, Sebastian, Gonzalo, and their positions at court.

Fortunately, the residents of this prehistoric Neverland or Gilligan’s Island are instantly differentiated, thanks to Gina Brafford’s florid costume designs – beginning with Atkinson wholesome Oklahoma farmgirl look as Miranda. Hard to say which is more outré, the winged Viscioni evoking the gladrags of the ‘60s or Robert Brafford as Caliban, looking like he’d been freshly belched from the belly of a whale.

Maybe the flowery Ariel outfit should get the nod because she’s so sassy and blithe all evening long. So: Calling on Hensley to give Viscioni a sassier final exit. She deserves it no less than Rowe, who asks for it in the touching Epilogue.