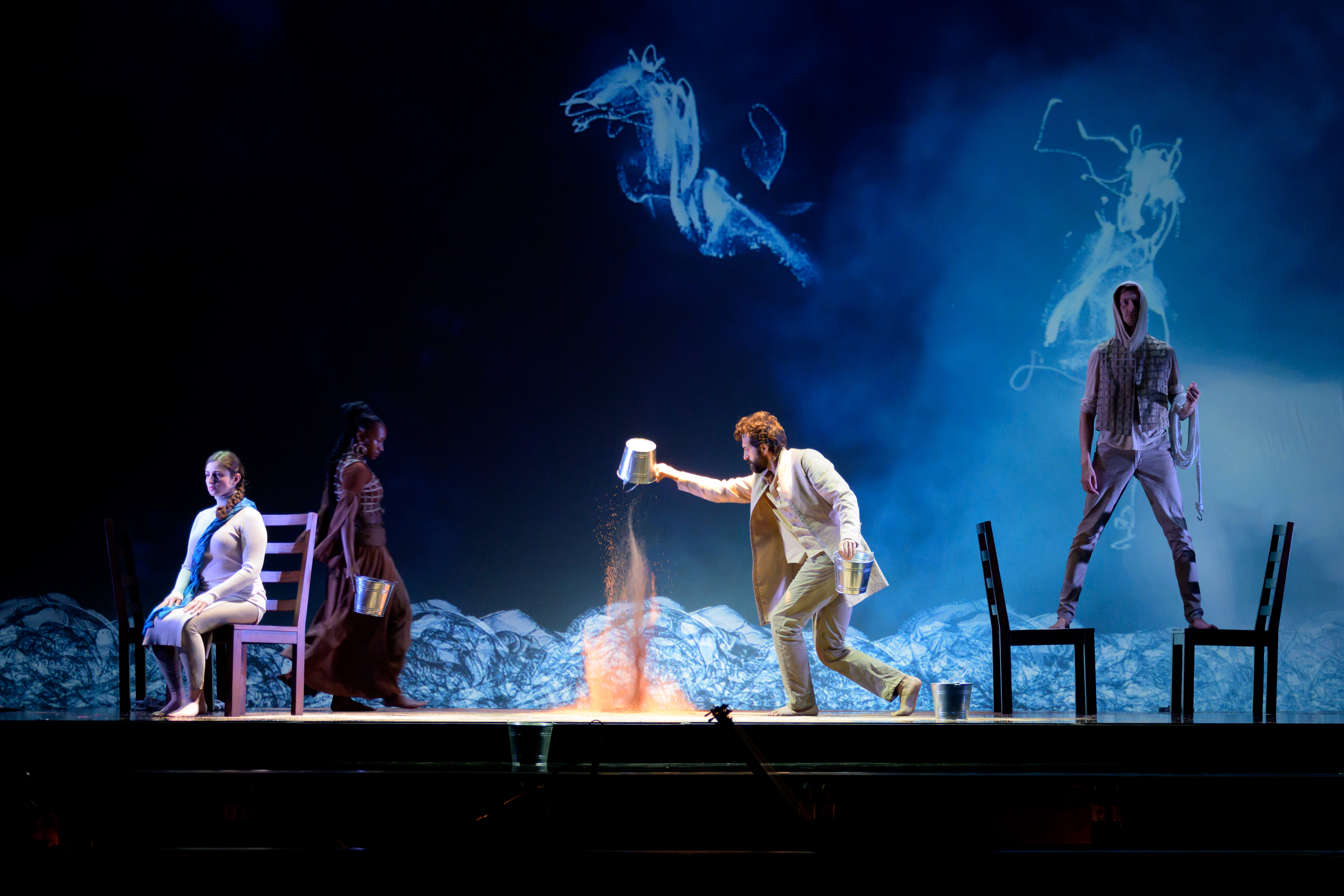

Review: Sphinx Virtuosi @ Charlotte Symphony’s Annual Gala

By Perry Tannenbaum

October 9, 2024, Charlotte, NC – It’s always encouraging when an annual gala at least partially sheds its patrician aura of black ties, ball gowns, and champagne toasts. So I heartily applauded Charlotte Symphony’s musical director emeritus Christopher Warren-Green when, instead of mentioning crass sums of moneys raised or needed, he notified us that a part of tonight’s proceeds would be sent to those in dire straits in Western North Carolina in the wake of Hurricane Helene. In an even more unexpected gesture, the evening’s guests, Sphinx Virtuosi, announced that they would linger in Charlotte to play an additional concert on Friday at Charlotte Preparatory School – free if you bring a Hurricane Helene contribution.

They all worked well, together and apart, in gifting the gala audience at Belk Theater with a fine show, though not exactly what was initially planned. Or even what was listed in the printed program. Instead, a series of changes to the program were announced by email before and after the program went to press. Even then, a couple of new wrinkles emerged after the lineup seemed to be settled in the last inbox update on September 19. Maybe the plutocrats who dined and toasted earlier at the pre-concert cocktail and dinner sessions got a heads-up.

As a result of the first alteration, changing the title of LA-based composer Levi Taylor’s from American Forms to Daydreaming (A Fantasy on Scott Joplin), the opening segment of the concert became an explicitly extended tribute to Joplin. Actually, the Overture from Joplin’s only surviving opera, Treemonisha (1911), was nearly as new as Taylor’s offering and similar in length. The orchestration chosen by Warren-Green, arranged by Jannina Norpoth with Jessie Montgomery (a Sphinx Medal of Excellence winner in 2020), was premiered last year in Toronto as part of a “reimagining” of Joplin’s opera, so it didn’t quite sound like any of the handful of versions that Spotify can offer. Principal clarinetist Taylor Marino was brilliant playing the catchy recurring theme, an instrumental assignment that Norpoth reaffirms, but principal trumpeter Alex Wilborn’s spot struck me as a lively improvement upon Norpoth’s predecessors.

In a shorter, no-intermission program, it was nice to have a proper mood-setter leading into Taylor’s premiere – and Sphinx Virtuosi’s entrance – rather than a genial throwaway aperitif. Paradoxically, the Joplin overture, aimed for an opera house, was not as raggy as Taylor’s new work, an homage to the Joplin music we’re most familiar with. Personably introduced by cellist Lindsey Sharpe, the piece had an engaging solo spot for principal cellist Tommy Mesa and a refreshing jauntiness. Amazing how much more highbrow and classical the Joplin idiom sounds when you ditch the piano so justifiably associated with the “King of Ragtime.” Taylor took a well-deserved, enthusiastically applauded bow when concertmaster Alex Gonzalez pointed him out in the audience.

Sphinx’s outreach to Helene victims is quite natural when you consider its DNA. Conceived in Ann Arbor at the University of Michigan in 1997, Sphinx quickly became an important of young Black and Latino talent with its annual junior and senior competitions, open to musicians up to age 26, and its Performance Academy, a competitive boot camp, where faculty members include Norpoth, Gonzalez, and second violinist Rainel Joubert – who would play in the Delights and Dances string quartet when the Michael Abels composition, commissioned by Sphinx, had its Charlotte premiere.

The full ensemble departed – all too briefly – as Warren-Green and CSO delivered a more familiar Leonard Bernstein overture to his opera, Candide. If Sphinx had lingered offstage longer, the CSO performance might have been more prudently paced. Dynamics were OK, but when piece started off too swiftly, there was little room for Symphony to speed up when the piece thundered and thrust to its climax. The whole acceleration plus crescendo effect, so exciting in multiple Rossini overtures, was never even a possibility, surely the nadir of Warren-Green’s work with CSO as far back as I can remember.

Then the listed world premiere of Curtis Stewart’s Drill went AWOL, along with guest percussionist Britton-René Collins. This surprise was less of a disaster than the lackluster Bernstein, for the Sphinx Virtuosi returned instead with Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s Allegro Moderato, the opening movement from his Four Novelleten (1903) for string orchestra. So many of Coleridge-Taylor’s principal works have yet to be recorded that it’s probable that this excavation, listed as Op. 59 in Wikipedia, has yet to get a hearing outside of Sphinx’s orbit – another gladdening example of the ensemble’s vital and generous outreach.

All the remaining works were glorious, throwing the Bernstein blooper far into our rearview mirrors. It helped a little to know your Vivaldi when Sphinx moved upstage to merge with the CSO as tango king Astor Piazzola’s “Verano Porteño (Buenos Aires Summer)” movement from his Four Seasons of Buenos Aires filled the stage with violinist Adé Williams as guest soloist. For those who saw Aisslinn Nosky playing the complete Vivaldi at the Charlotte Bach Festival, the Piazzola Four Seasons evoked some pleasant nostalgia, especially since the Festival Orchestra, like the Virtuosi, often performs without a conductor.

Williams, a winner of the Sphinx Junior Division back in 2012, still played with youthful vitality and joy. Both Symphony and Warren-Green were obviously fond of her playing, her swooping glisses, and the tango twists Piazzola brought to his baroque inspiration. Controversial in Argentina for his modifications of the trad tango – cab drivers often turned him away! – this summer piece was popular enough for Piazzola to draw encouragement for him to complete his seasonal cycle. The Belk audience responded favorably as well, with their first standing O of the evening.

The Abels piece was an even longer, grander gatherum, with the string quartet arriving upstage where Williams had just stood. Joubert and CSO principal second violin were to Warren-Green’s left opposite CSO principal viola Benjamin Geller and cellist Gabriel Cabezas, the Sphinx Medal of Excellence winner in 2016. The Delights were rather delicate before the composer, who famously co-wrote the acclaimed Omar with Rhiannon Giddens, gradually ramped up to the Dances.Cabezas was more than able to eloquently launch Abel’s slow-building piece, which tacked leftward after his engaging solo with additional solo spots for the rest of the quartet members.

Nor was Abels in any hurry to layer on the orchestra, for their first contributions were background pizzicatos behind the full quartet before they picked up their bows. The piece is no less than the title work on a 2013 album recorded by the Harlem Quartet and the Chicago Sinfonietta conducted by Mei-Ann Chen. Definitely worth a listen if you missed the gala – and Abels’ Global Warming leads off the Sphinx Virtuosi’s recent Songs of Our Times release, their first album. Some rousing fiddling embroidered the loud and lively climax of Delights & Dances, easily the most epic piece of the night, programmed in exactly the right spot.

Mexican composer Arturo Márquez’s Conga del Fuego Nuevo (1996) was no less appropriately placed in the encore slot, starting up white-hot and danceable without lowering its flame. Fully recovered from his Bernstein misadventure, Warren-Green not only led the combined ensembles zestfully, he exhibited some winsome showmanship of his own, not only bidding Wilborn to stand up for his solos on muted and unmuted trumpet, but also commanding the winds and the brass to rise when moments came. How can a piece we’ve never heard before sound so familiar? Maybe via discreet borrowing and insistent repetition. No matter, CSO’s jolly encore became a curtain call at the same time – and a wonderful welcome to the 2024-25 season. Hopefully, the Coleridge-Taylor and the Abels were previews of the next Sphinx recording.

Photos by Perry Tannenbaum