Review: Hadestown at Belk Theater

By Perry Tannenbaum

The last time HADESTOWN sauntered into town with its jazzy swagger was almost exactly 18 months ago, Election Day 2022. Perfect timing. When Matthew Patrick Quinn as King Hades brought down the Act 1 curtain with “Why We Build the Wall,” the thrust was so hideously Donald-like that two MAGA maniacs sitting in front of us, clearly offended, huffed out of Belk Theater and didn’t return after intermission.

Well, Quinn and his tectonic shelf-shaking bass baritone voice are back in the title role – the chief reason why my wife Sue would return to see Hadestown a third time if he and the Anaïs Mitchell musical should come back yet again. Yeah, he is that good. And even though The Wall is a bit in the rearview mirror as a national topic of conversation, the satanic aura of Hades still adheres to the corrupt kingpin of the GOP.

Maybe in a different way this time. More than Hades’ striking xenophobia, a strange attitude for a king of Hell, my lingering distaste was for the god’s rabble-rousing dictatorial strut. #MeToo was probably past its fullest bloom in 2022, though it still weighed on the elections, but in 2024, I couldn’t help paying closer attention to Hades’ “Hey, Little Songbird” propositioning of Eurydice.

When she eventually followed the slick monarch to the Netherworld and climbed the stairs to his boudoir, where she would sign away her soul behind closed doors… Yeah, Eurydice’s slow assenting ascent turned my thoughts northward to Stormy Daniels testifying in a Manhattan courtroom earlier that day in the hush money trial. Another little songbird.

To dwell on how deeply Hadestown resonates with the American political scene is to ignore that it first workshopped in New York before the master of Trump Tower declared his candidacy. It also disrespects how well Mitchell retold the story before it developed its adhesive powers. We see Quinn as Hades soon enough, but he doesn’t assert himself until he becomes impatient for Persephone’s annual return to the underworld after she has brought on spring and summer here above.

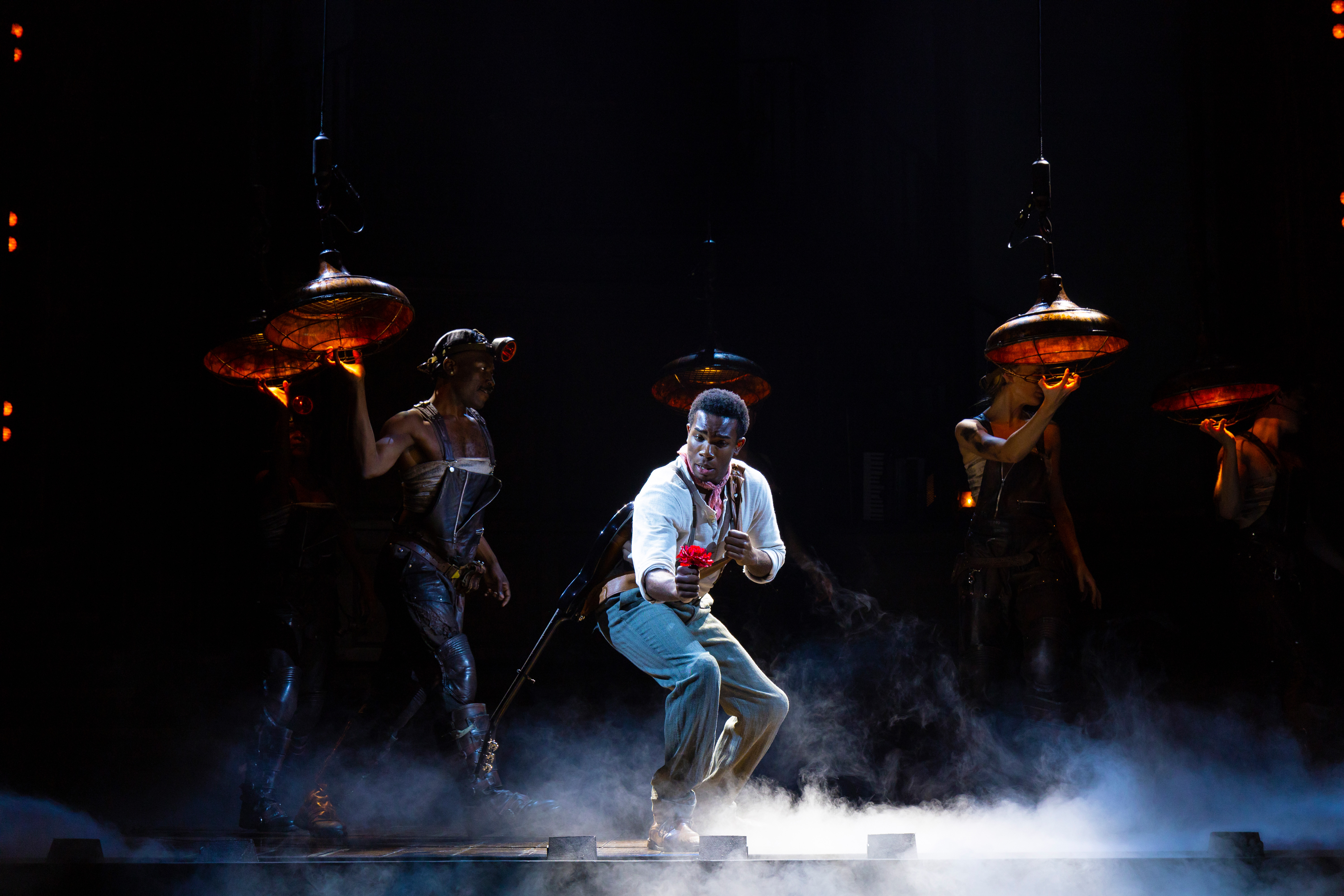

Until then, Lana Gordon as Persephone and Will Mann as our host/narrator Hermes are the prime charismatics. Next to their flamboyance, Orpheus and Eurydice are rather tame, despite J. Antonio Rodriguez’s pure high tenor and Amaya Braganza’s street-urchin perkiness. Musically, Mitchell lavishes her best invention on Hades and Orpheus, which makes sense since Orpheus has always represented the power of music while Hades, alias Pluto, has always stood for mindless greed.

Gordon and Mann are expected to light up the stage with their outsized personalities, their pizzaz, and eye-popping color – costume designer Michael Krass’s best – chief reasons why Hadestown rolls along so grandly, backed up less brashly by Braganza’s kooky charm and Rodriguez’s botanical magic.

But Mitchell’s book is also provocative, darkly portraying the world above as stricken by an apocalyptic nuclear winter or irreversible climate change, needing Orpheus’s musical magic to set things right and Eurydice to supply him with inspiration and encouragement to finish his cosmic song. The core of this world-changing song, appropriately enough, is wordless. Mitchell gives us a nice touch of the universal here.

Mitchell herself was the original Eurydice when her show first surfaced in New England in 2007. For me, that explains the most annoying, least enduring traits of Hadestown: its devout unpretentiousness and its dogged determination never to proceed too far without undercutting itself and reminding us that this is merely theatre. We’re having a party, y’all! Have a drink!

All the musicians are perennially onstage with the actors, particularly the ponytailed Emily Frederickson, who occasionally sashays among the cast with her trombone when called upon for her tastiest licks. For backup vocals, three more angels are engaged as the Fates – Marla Loussaint, Lizzie Markson, and Hannah Schreer – all of whom pick up various instruments during the evening. Could we have Orpheus trudging out of Hades, a fearful but trusting Eurydice behind him, without being tracked by a backup group?

Mitchell and director/developer Rachel Chavkin apparently didn’t think so. Maybe they’ve never experienced Christof Glück’s Orfeo ed Euridice at the Met’s Lincoln Center production, where the legendary newlyweds walk up a long, steep, irregular staircase splayed against the upstage wall, carrying torches to light up the tunnel.

Or perhaps they had seen that opera and realized that youngsters in the audience, not knowing how Vergil and Ovid told the tale, would be bummed by the tragedy if Glück hadn’t appended a happy ending. The whole evening seems cushioned by Chavkin and Mitchell’s worry that they might lose a key demographic along the way if the seriousness of the tragedy remained undiluted by mirth, merriment, and David Neuman’s most festive choreography.

Not to worry, when the Fates take their toll, the hearty, genial, and avuncular Hermes will be there to console Orpheus and all his bummed fans. Along with a big brassy jazz band. Raise another glass!